The Wholly Trinity

Self, Body and Landscape: An Interview with Zachari Logan

In 2010 Zachari Logan painted a large 118 x 210-inch oil on canvas called Beautiful Losers. The work depicts eight self-portraits; in all of them he is partially or completely unclothed, except for athletic shoes and socks, and in two he holds one of the five cats who share the painted space with him. His multiple selves are engaged in a series of activities that include carpentry, considering where to hang a potted plant, performing exercises and standing on a small stepladder. The ladder is a prop in two versions, and in both cases, he casts a blue shadow onto the wall, as if his body were looking for a way to copy itself again.

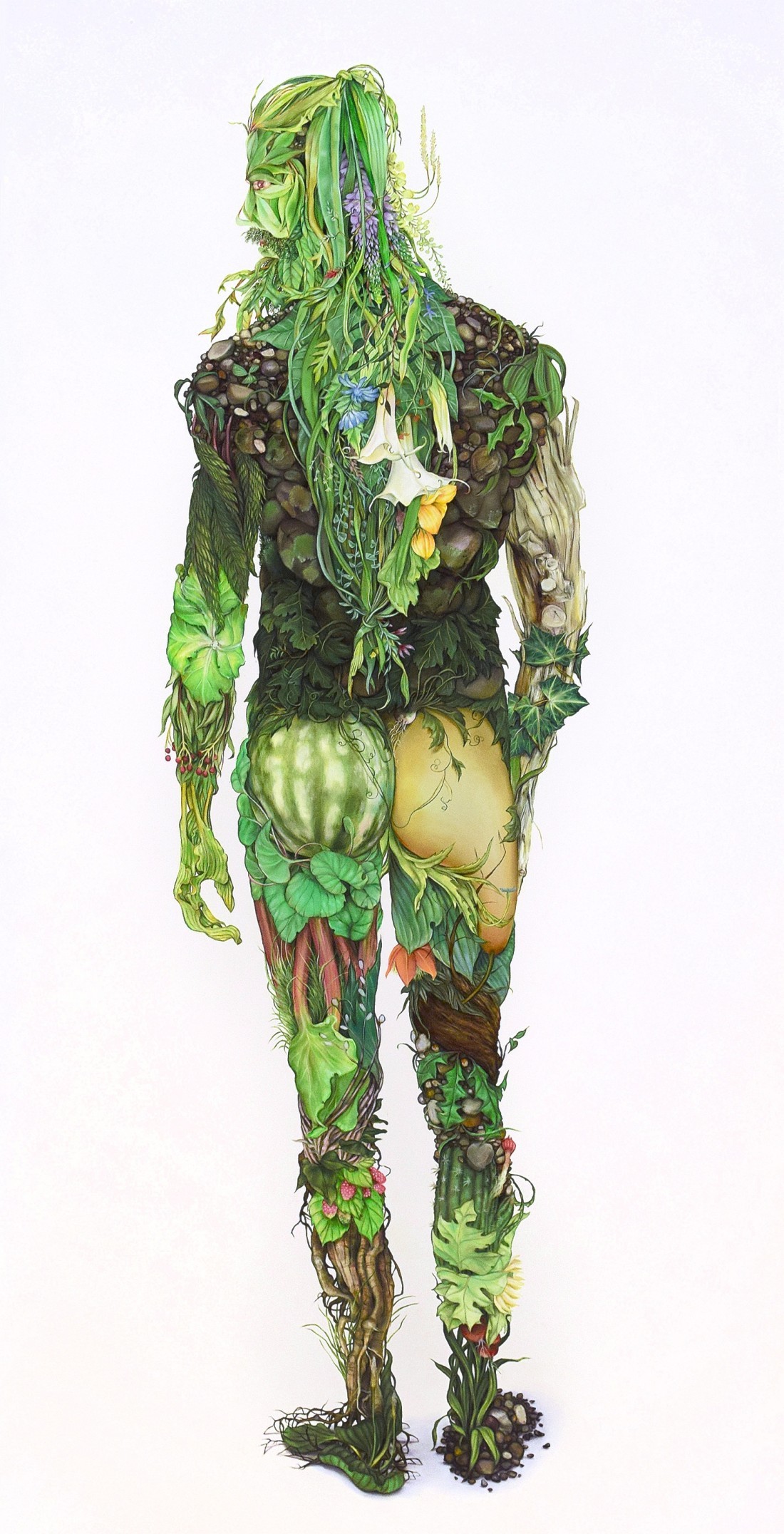

In Beautiful Losers he played the numbers game and made self-portraiture parthenogenetic. It was an anomalous experiment because most often his work reduces the number to one. He sings, along with Walt Whitman, a song of himself. It is an attractive arrangement; Logan is 6’4” tall and physically fit, and his body is always available and amenable to him as a subject. It has allowed him a world of pictorial possibilities in that he can attach himself to any number of contemporary or historical representations. Logan is a gentle marauder in the corridors of art history, where he has been engaged with the work of Jacques-Louis David, Théodore Géricault and Eugène Delacroix. While Logan’s interests are omnivorous, he has been especially attracted to artists who find in the natural world a way of augmenting the human. Mary Delany, the 18th-century botanist and collagist, is one of his discovered mentors, which is not surprising for an artist whose pastel on black paper drawing is called Human Heart Made of Plants, 2016. He is equally attracted to Giuseppe Arcimboldo, the 16th-century painter of fantastic plant and animal comminglings. In Green Man No. 2, 2018, pastel on paper, Logan takes Arcimboldo’s focus on portraiture and stretches the combination of flesh and floral across the entire body. Logan regards the works of the Italian Renaissance painter as completely consistent with his own philosophy, “which basically is: there’s no separation between land and body.” No artist since Arcimboldo has gone as far as Logan in grafting together the human, the animal and the botanical. His practice, which includes drawing, painting, ceramics and installation, is terrifically inventive and prodigiously productive. In the drawings you will find his own body covered in insects; you will see his physiognomy become a perch, a nest and a feeding place for innumerable birds. There is a darker side to this grafting; the natural inhabitations can be claustrophobic and destructive when the fecund drifts towards the freaky. In Emperor’s New Clothes, 2011, his entire body is covered in monarch butterflies, an image that goes well beyond Richard Avedon’s 1981 Beekeeper portrait. But the butterfly envelopment is lyric; in Swarm No.1, 2013, the insects seem like an invasion, and in Wild Man, 2016, Logan is in danger of disappearing in the ever-growing floral expansion. But these are my hesitations. For Logan there is nothing foreign or unnatural about these reimaginings. The body is involved in a constant state of transformation; it is both being and becoming.

Zachari Logan, Green Man No 2, from Natural Drag Series (After Arcimboldo), 2018, pastel on paper, 94 x 46 inches. Private collection, Toronto. Courtesy the artist and Paul Petro Contemporary Art.

Interwoven with this aesthetic is an uncompromising politic that takes on sexual and environmental dimensions: “What we do to the land we do to ourselves.” Logan is a proponent of the ditch as the only uncultivated terrain in his home prairies. (Logan grew up and studied in Saskatoon and now lives in Regina.) The ditch weeds that grow there are surrogates for the queer body and Logan sees these wild, queered survivors as having a “will to flourish.” That resolve became necessary in a homophobic culture in which the view expressed by his grade eight sex education teacher—sex involves “Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve”—is still an attitude that can be heard in the ethically dark corridors of a punishing and vengeful heteronormative society. Overcoming uttered and latent homophobia is only the most obvious problem faced by queer individuals.

In this regard, Logan’s “will to flourish” recalls the finest long poem ever written on the prairies. Robert Kroetsch published Seed Catalogue in 1986. The poem used as its central metaphor the catalogues mailed to farmers in the 1920s by the McKenzie Steel-Briggs Seed Company. The company would pitch its flower, vegetable and grass seeds, extolling their virtues and advantages. Among the most persuasive was the recommendation for brome grass, Bromus inermis, because it so completely possessed the qualities necessary to survive a hostile climate: “No amount of cold will kill it,” “it withstands the summer suns,” “the roots push through the soil throwing up new plants continually.” But what makes brome grass special and what makes it stand out among the seeded offerings is that it “flourishes under absolute neglect.” Kroetsch’s brome grass and Logan’s ditch weeds have the same character. The seeded plants faced a seasonal hostility; the queered weeds had to overcome a resistance that was social and sexual. But what their convergence makes clear is that generation after generation, prairie writers and artists continue to seed and grow their own uniquely wilful and wildly successful plantings.

The following interview was conducted by phone to Zachari Logan’s Regina studio on October 6, 2021.

Zachari Logan, Wildman No. 2, 2012, blue pencil on Mylar, 15 x 30 inches. Private collection, Saskatchewan. Courtesy the artist.

BORDER CROSSINGS: You said, in a conversation last year with Wayne Baerwaldt in Public 62, that the observations in your writing seem to be related to your childhood. Is that more the case in your writing than in your visual art practice?

ZACHARI LOGAN: Yes. I don’t think you can ever get away from your childhood or your upbringing, in anything that you do. But for whatever reason, I tend to conjure certain visual memories that relate to my childhood more evidently in the writing. I wouldn’t say that it’s not in my visual work, and there have been pieces that are obviously related to my childhood and my identity. I did a series of text-based drawings where I would use the same word or phrase over and over to build up the images. One was a portrait of me at 26 months old and the word I used was “faggot.” The word shifts when you place it overtop of the image of an innocent child. That series of drawings was based on the idea of insult and how it transforms the queer body.

You did your MFA at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon, where you worked with Alison Norlen.

Alison’s own work—its scale and method and that she worked on paper—was influential, but she was formative for a lot of reasons. While I was at Saskatoon, I started working in oils, which I hadn’t done previously, and I began to delve into a much more personal iconography. I had been working with images of other men from ubiquitous sources and Alison said, “It might be interesting to turn that lens on yourself.” Before that I’d hadn’t thought about self-portraiture and had no desire to do it, but it became a staple of my work. My work is not figurative in a traditional sense any longer, but I see my body and the idea of self-portraiture intimately woven into the work. It’s becoming more about a sense of abstraction and landscape, but it’s still very bodily, very figurative.

You seem to be something of a museum junkie. You have said that in museums you find your humanity.

I had a bit of an epiphany when I went to New York for the first time in 2004 just after my undergrad, when I was able to stand in front of a remarkable amount of artwork that I had only seen in books. I also had an opportunity to show all the work from my master’s exhibition at a works-on-paper gallery in Paris and during that time I went to the Musée d’Orsay and to the Louvre for the first time. It was such a visceral experience, the sheer physicality of the paintings, coupled with the fact that I’d been evoking references from these works solely from text-based sources, and there I was in front of them. I had several Stendhal moments that week, so I devised a residency that allowed me to go back the following summer. For three months I went to the Louvre and drew primarily from the neoclassical and Romantic paintings by David, Géricault and Delacroix in the Grand Hall, noticing the endless subtleties that are lost in reproduction. When I’m in a museum it’s like I’m having a conversation with a ghost. I feel as if I’m conversing with the person who made that object and accessing information from what they left behind.

You go to Europe and you draw from the museum collections. This sounds vaguely 19th century, like your version of the Grand Tour.

It feels outside of time in a way. I become obsessed with particular artists for reasons I can’t entirely explain. Like Mary Delany, whom I happened upon when I was overwhelmed wandering through corridor upon corridor in the British Museum. Suddenly there were these two tiny, botanical pieces and they enveloped me. I became obsessed with her and ended up going back and studying her works in person.

Zachari Logan, Eunuch Tapestry No. 5 (detail), 2015, pastel on black paper, 84 x 288 inches. Collection of the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario. Courtesy the artist and Paul Petro Contemporary Art.

Zachari Logan, installation view, Eunuch Tapestry No. 5, 2015, pastel on black paper, 84 x 288 inches. Collection of the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario.

When did you discover Giuseppe Arcimboldo and realize that there was an affinity in the way you both saw the relationship between the natural and the human?

That was on another residency in 2012. I was invited to do a project with a gallery called Schleifmühlgasse 12–14. They’re an exhibition space and artist-run centre that invites two international artists a year to come and do a project. Through another Austrian artist my work was suggested to this program, the director was intrigued and I was invited. I said I’d love to look at Viennese collections and see if I could do something in response. I had finished works that were included in the show, but I also did a series of drawings while I was there. Vienna is a treasure trove because the Habsburgs were collectors of works on paper, so the Albertina has all those remarkable watercolours by Dürer, like Young Hare and The Large Piece of Turf. The other artist who is part of Vienna’s collections who really affected me in person is the Italian mannerist painter Arcimboldo. You understand how contemporary his works are when you see them with your own eyes. They don’t seem like 16th-century objects. They feel completely fresh and in line with my philosophy, which basically is: there’s no separation between land and body. We are the landscape. I saw that physically embodied in his work and I wanted to portray it with my own body, almost like a drag performance. So the subtitle for all my works that are an amalgam of flora and fauna is the “Natural Drag Series.”

When you decided that the catalyst for your art is your own body, does that mean your work is an extended experiment in self-portraiture?

I would say that’s pretty accurate. It’s strange because I saw a lot of naked men when I started to delve into images of the male body in art history, but I didn’t see what I felt were queer bodies. I didn’t feel represented. One of the reasons I decided to use my own body was practical. I was easily accessible, but I also think it added a personal, if not psychological, element to the work. I started to portray characters and make references to famous art historical tropes or images by turning a queer lens on them. I felt like I was using my body to say something societal in those works, but they didn’t feel like self-portraiture. It was when the body started to disappear or be covered over or encroached upon that they started to feel much more personal and, in a way, much more me.

I’m interested to hear you say that you couldn’t locate images that represented you in the imagery you had been looking at. What about all those Saint Sebastians? Many of the painters who made them were queer, so a secret code seemed to be operating in much of the work.

Yes. At a certain point I realized that this language existed. I started looking at more Catholic imagery and thinking about this strange mix of sex and torture and transcendence. I realized the bodies were very beautiful and they didn’t look dead trade. Saint Sebastian, of course, was killed with arrows, which were the tools of his trade. I also noticed in works in the Grand Hall a beautiful homosocial, if not homoerotic, intimacy, with the placement of bodies and hands in many Romantic and neoclassical compositions. The centre would be “bravado central,” Napoleon or his visual stand-in, Caesar, in a Roman fantasy à la Imperial France, but off on the peripheries were these taut, beautiful, muscular men, holding hands, emoting and being suspectly languid. In fact, in the painting Beautiful Losers, I’m echoing with my own body the gestures, interactions and absurdities I collected while studying these periphery bodies.

Zachari Logan, Naked In The Roses, 2018, red pencil on Mylar, 9 x 12 inches. Private collection, Toronto.

Jeff Wall says that all art is contemporary art, so everything is susceptible to being reconsidered. Because your reconsideration is filtered through a queer lens, it gives you even more flexibility in what you can do with art historical images.

I didn’t know that quote by Jeff Wall, but I utterly agree with it. Yes, all it takes is a fresh eye doing the looking. We don’t live in a vacuum. That push in modernism to do something new isn’t in my lexicon. I look at Jackson Pollock and I see Frans Hals. I don’t separate those things. It’s not like there was a stop point. The world has shifted because of technology and the art of the 20th century reflects that, but it doesn’t go outside of time. So that idea of the modern being completely different and new seems antithetical to me.

You have this idea of “ditch aesthetics” and that queers are ditch flowers and proud of it. How and when did it come to you as a way to think about your own identity, and to recognize that both nature and the body could be integrated in the ditch?

It may sound strange, but it began with travel. When travelling I would often think about being back home and about the landscape. Part of that involved bodies in space, bodies in place, and thinking about figuration in a slightly different way. I was also photographing a lot of things and I realized that instead of buildings or monuments, what I was photographing were quiet garden areas, open vistas and plants and fauna. I did a drawing during a residency around Short Mountain, Tennessee, in 2011. I had been deeply affected by the beautiful landscape there, which was so different from what I was used to in Saskatchewan. Around that time, I was invited to be a part of an exhibition called “Domestic Queens” that was curated by Evergon. It was all about men living in domestic partnerships with other men. I had a vitrine that was 30 feet long, so I did a very expansive drawing. It was the first time I started to think about the landscape and the body, and about their not necessarily being separate. My earlier works were large self-portraits that were based on the language of painting in terms of how I posed my body, and they were defined or delineated by a single shadow. With this massive drawing, Vignette (2011), the landscape started to sink into my work. It ended up being a family portrait; it was me, my husband, Ned, and our two cats in this pre-lapsarian garden. But the garden was built from species of flora and fauna from Tennessee and Saskatchewan. I drew plant life from Tennessee while I was there, I also took photographs and finished the drawing in Saskatchewan. It became a fictional dreamscape, constructed the way a Dutch still life might be and made to look completely naturalistic but fictive, as the species depicted were never blooming at the same time. I started thinking about space in that way more generally, and thinking more specifically about ditch flowers and weeds, and it quickly became a lot clearer. That was the catalyst. Soon after, I began the “Eunuch Tapestries Series” where what became prominent was the foreground, the ditches and the mix of plant life from different places. I started to think about queer bodies on the prairies and of those liminal spaces as queer spaces, but I think it applies pretty much anywhere in North America and around the world. Also, Saskatchewan is a landscape that people feel is completely untouched, but every square inch of it is manufactured for human consumption. One of the few areas of wildness that haven’t been destroyed by this monoculture are the idiosyncratic ditches where these plants thrive. There’s an additional layer in the way humans speak about certain types of plants; they’re not consumable, so they become “disregardable.” In our society, someone is sexually less desirable if they’re queer. So I saw that language overlap, and the space became an important metaphorical space for queerness and the weeds for queer bodies themselves.

I want to talk about rewilding in the context of the ditch aesthetic and the land/body intersection. In Green Man No. 2 (2018), on the figure’s left leg, just below the buttock, there are green leaves that have stalks and those stalks read like musculature. I was reminded of those transparent Illustrated Man models that we had as kids, where you could see the internal organs and the arrangement of muscles. It made me think that you were consciously making the flora in the drawing correspond to the structure and tone of the actual physical body.

I was thinking about the systems of the body and how musculature and the skeletal system work, and I wanted the drawing to have that sense of physicality. In my third year of drawing at U of Saskatchewan, I went for extra sessions in the anatomy department. I learned a lot about drawing the human body that way. The only thing that grossed me out was the smell of the formaldehyde. But my drawing is completely fantastical, although when you’re in front of it, the physical weight of the working body is believable. When you’re drawing a body, you’re thinking about the weight of the leg on the floor and the shadowing, but you also have to think about how the musculature sits as it’s doing its job. I should add that there’s also a slight depiction of a jock strap that goes across the buttock. It’s something I put in as a little peekaboo and almost no one notices it.

Zachari Logan, Wreath No 3, Levitate after Mary Delany, 2016, pastel on black paper, 59 x 60 inches.

In a piece like Bones, Stones, Petals, Leaves, some of the “Pool” series and the “Boneyard” series from 2020, the plants have live sprouts and they sprout skulls, bones and vertebrae. The connection reminds me of Leaves of Grass, in which Whitman says, “every blade of grass proves there is no death.” I sense that recognition in your work as well. It’s not death we’re looking at but a process of regeneration.

Yes. In my collection of poems there’s a direct reference to Leaves of Grass where I describe my husband’s shoulder hair as “leaves of grass illuminated by an electric streetlight.” Death is part of the process of life, so an acceptance of one’s own mortality is reflected in the work. I grew up during the AIDS pandemic and I remember our sex ed teacher in grade eight saying, after we had watched a video that included an interview with a man who was obviously ill with the virus, “Well, God made Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve.” By the time I was in grade eight I knew that I was queer and, because of AIDS, I had accepted the fact that I might die young. So an acceptance of mortality was part of a process of regeneration.

Whitman “sings the body electric,” and you sing the body erotic. Your work is charged with eroticism, and through visual representations like floral ejaculation, you sexualize both the body and nature.

I want to normalize the joy of experiencing your own body. We’re all sexual creatures and we all deserve to enjoy our own bodies and have control over them. Among the earlier self-portraits I did of myself as Christ and saint figures there’s only one that makes me a bit queasy. I have several exposed bones, so my shin and thigh bone are actually protruding out of the skin. It was based on researching saint figures but also on images of construction accidents. A lot of the depictions of saints romanticized and beautified the violence of Catholicism, but I wanted mine to be more visceral and jarring. They were displayed at the Mendel Gallery in a show called “Flatlanders,” which was about contemporary Saskatchewan artists, and the only complaints focused on nudity. No one mentioned anything about the violence. They weren’t nude, but they were bathed in blood and violent things were happening to these bodies, and not a single thing was said about the violence. Mainstream television will show you someone’s head explode at 6:00 p.m., but you can’t say the word “fuck” or show a penis. It’s absurd.

I want to talk about the intimacy of detail in your work. Green Man No. 2 plays wonderfully with ocular touch. If you look at the man’s derrière, green roots and tendrils slip into his ass crack and then his butt cheek on the other side is cupped by the leaves of a plant. All those are details of amorous seduction, aren’t they?

That kind of detail is also in other pastel drawings and in my smaller works on Mylar. The act of drawing is such an intimate one, and for me, especially with pastel, there’s no separation between the materials and my body. I’m mixing everything with my fingers, and in the expansive tapestry works, I get to a point where my fingers are bleeding because I’ve rubbed them raw. So my DNA is literally in the work. Then I have to stop for a while and let the callouses build up. The process is incredibly physical while being tender to the touch. Caressing chalk pastel with my fingertips is a form of attention to detail that adds to the sensuality of what I’m depicting.

Zachari Logan, South Saskatchewan River (Grotto, after Van Eyck), 2019, red pencil on Mylar, 9 x 12 inches. Private collection, Toronto.

That same slippage happens in your poetry because you compose nature as a body. In “Grasslands” the chest hair becomes unkempt grass that comes over the top of a t-shirt; in “The Disappearing Sky” the dry tulips look like “arthritic hands”; in “Invasive Spaces” the skin reveals veins that resemble rivers on a map; and in “Flowering” you imagine your testicles as “downy, green, poppy seeds.” You do it in sculpture as well; the oval ditch with artist’s hair has a strange sexual feel about it. All your art languages—whether image, object or poem—seem to be involved in a process of auto-eroticizing themselves.

Well, if you think about flowers, which I obsess over, they are the genitals of the plant. I thought about semen and stickiness and the idea of the flower as the genitals. So all those things are swirling around in my head. Then body hair becomes an important aspect of those works. They become crowns in a way, and it’s this celebration of the enveloping idea of pubic hair being flora and fauna. I have an idea how I’m going to do the drawing and I know that the depiction of the penis is based on what it looks like, but how it’s adorned and how it gets formed come out of the process of doing. I think, here’s where I want to place a couple of insects around the penis. So I have only a general idea about the composition.

We’ve talked about the regenerative possibilities of what you’re doing with landscape, but there are works—the “Vanitas” series, the Grotesques, the Wild Man drawings and the Swarm drawings, from the “Enigma” series—that suggest a more unsettling dimension. You talk about noticing in Margaret Atwood’s short story collection Wilderness Tips “an ambiguous sense of dread.” Do you think that your work has an equivalent sense?

I do. I think it relates to phobias in our own evolution as a species. There has to be a reason why people have a greater fear of spiders than of death. In Emperor’s New Clothes (2011) I’m acknowledging one of those fears by completely covering my body with monarch butterflies. I was also thinking about the phenomenon of the Mariposa where these tiny creatures fly enormous distances, and when they land on a tree branch, their weight can break it off. It’s remarkable. I was thinking about how many butterflies it would take to tear my arm off. So the image came from my imagining that happening to my own body and asking the viewer to do the same. But I think Swarm No. 1 (2013) is potentially a more disturbing drawing than even the monarch piece. Because you still see the eyes and the mouth of the person. They are not completely covered over but covered over just enough.

Zachari Logan, Leshy No 2 from Natural Drag Series, 2016, pastel on black paper, 59 x 75 inches. Private collection, California.

You seem to luxuriate in being enveloped by crawling winged things or being fed by birds. Some people would go out of their minds thinking about those drawings, let alone living through the making of them.

I wanted to play on the northern Renaissance genre of the vanitas and memento mori and the Dutch still life and transform my face into a Dutch still life. I put my face in as the skull and built the rest around it. In one sense, it’s a banquet, it’s a bouquet, it’s a meal.

I want to talk about scale. Obviously, you’re not in the slightest way intimidated by it.

No. It’s simply a case of having enough room in my studio.

You mentioned Vignette, the graphite family portrait, which is 9 x 18 feet, and then Rococo Sky (Guardai in alta e vidi le sue Spalle), the mixed media piece that was in the Remai Modern, is 45 feet long. What is it about scale that you so naturally gravitate towards?

Well, I like tiny and intimate and I like huge and expansive because they do something psychically different to the viewer. As I’m doing it in my studio, there is the joy of working across my walls. I absolutely adore it. It’s also creating a visual experience that is expansive but also detailed. I want to slow down the viewer and get them to spend more time with a static image. With a drawing, you have to work to be cognitively engaged and entertained. I want to create something that takes time to go through and to contemplate. And I also want to do that with smaller scale works. Another piece in that show at the Remai, which is called Bronchia (2020), is a collection of images from different green spaces that I visited around the world, in Austria, Canada, the US, the UK, Spain and France. I built up the surface to create a teeming landscape that’s incredibly dense but within a very, very small space. Again, it is about creating and holding an engagement with the viewer.

You seem incapable of not working in series. You need numbers. An idea comes to you and it seems to explode into possibilities.

I think that’s how I would describe it. I work in series and I do need numbers because I don’t feel like I’m ever fully done with something. I think the last piece that I had completed in the “Eunuch Tapestries Series” was in 2015 and I’m thinking about a new piece that combines two different series. I have done that as well in more recent works, like the pieces that are the most massive drawings I’ve done to date. They are related to the phenomenon of auras, ocular disruptions I experience at the onset of a migraine, and reference in their titles, as well, the opening cantos of Dante’s Inferno. Again, there is the reference point to my body. So, yes, it’s a sort of explosiveness because how do you get out of your own brain? That’s the lens of your world.

The “Eunuch Tapestries” are fascinating. I know that they’re based on the Unicorn Tapestries (1495–1505) in The Cloisters, but one of the intriguing things about your eponymous figure is that he is hiding. What happens if the queer aesthetic gets unwilded? What happens if it gets normalized? Does that mean the eunuch wouldn’t have to be crouched down, that he could stand up straight in that landscape?

That’s a good question.

Zachari Logan, Ghost Meadows (detail of Panel 1), 2021, 50 x 108 inches. Remai Modern, Saskatoon.

Zachari Logan, installation view, Ghost Meadows, 2021, Remai Modern, Saskatoon.

There’s something of a romance about the idea of the outsider. So the rewilding of the world is a fabulous idea that has terrific romantic attachments.

I don’t know. I think that the character of the eunuch, which is a parallel overlap to the character of the unicorn, also relates to its complete individuality. Not its superiority as a unicorn but its individuality, which I was relating to myself and also to every created species, because in those ditch areas I’ll often amalgamate two different things. I’m also trying to get at a democracy among all the different creatures. So I’m hidden in the background or crouching and foraging or doing something ambiguous, but it’s more that I’m trying to say that my body, or the human body, isn’t the most important aspect of the landscape, it’s simply an aspect of the landscape. I don’t think that the drawing would be misunderstood because artworks shift over time, they’re never dead objects, they shift with the time that they’re in.

So the eunuch is very different from the eight self-portraits in a large piece like Beautiful Losers (2010), where nothing is hidden?

Exactly. I go from being the narrative to being an aspect of the narrative. But yours is a great question. I did talk earlier about normalizing everyone’s individual sexuality. Obviously, the endpoint would be the acceptance of gender and sexual difference, and the acknowledgement of how settler societies have transformed the gender and sexuality of Indigenous communities who had a perfectly integrated sense of sexual difference, including an acceptance of Two-Spiritedness.

Every generation reinvents its own art history and its own allegiances. In Saskatchewan there is a minimalist prairie aesthetic, but you literally go for baroque.

I appreciate the history of modernism on the prairies, but I have found that many of the artists who work with the landscape in Saskatchewan do so from a distance. So you’ll get a lot of flat prairie imagery; flat sky, very dramatic, beautiful imagery. I wanted to zoom in, get microscopic, and have a different sense of awe. I often find that people underappreciate the prairies. They drive through Regina and think it’s entirely flat and boring and treeless. But if you were to go 20 minutes in either direction, north or south, you would find beautiful valleys filled with many different species of plants and animals. So it’s their lack of imagination. There’s something liminal about Saskatchewan as a place. I wanted to investigate the beauty of gravel, for example, of the ditch flowers, of the weeds, of the expansive prairie grasses. There has been a movement, especially in the Southwest, of farmers who have basically given land back so that it can be restored to prairie swale. There has even been a move to put buffalo back into the landscape. I think for the first time in over a hundred years, a buffalo calf was born on Wanuskewin recently. Powerful things are happening right now.

Given the fluidity of your work and the way that time can also be retransformed, you couldn’t have found a more perfect myth than Daphne, the woman who is turned into a laurel tree. You have a series where you appropriate the story and you queer it. It’s a classic case of how rich the past can be and how mythologies can be used to recreate contemporary images.

And how Greek mythology can be tied to Saskatchewan history in the past hundred years. If you look, you see these overlaps. I don’t think anything exists in a vacuum when it comes to human history and storytelling and mythology.

I assume your wreaths are celebratory and not funereal?

Yes. They’re strange portals, like the one of Mary Delany called Levitate, after Mary Delany (2019). It has a lot of movement and a sense of beauty. They’re more about regeneration than they are about decay. I think they are more celebratory, but the thing about wreaths is that they can access both meanings. So this visual portal, this adorned circle, can go on one’s head, it can go on a wall, or it can go on a grave. It’s multi-faceted. The urns are a little more about death, like Moon Flowers (My Father’s Skin), which is a direct reference to the experience of watching my father die. He had liver cancer and he died very quickly; he was diagnosed on Thursday evening and he died Saturday morning. We were talking with the doctor that day about treatment plans and then he was dead. But on his deathbed he turned bright yellow because of what had happened with his liver. It was very profound and beautiful, but also haunting. So yellow is a difficult colour for me because I never associate it with happy and sunny and bright, as most people do. I always associate it with death. The drawing is a representation of that. And I used Datura flowers, which are personally very important to me and which are poisonous, to hint at the uncontrollable nature of death.

In “Flatline” you refer to Bellini’s “beet face” and the colours you list are reddish peach, bruised apricot and anemic yellow. That’s not your melancholic blue.

Precisely. I find a lot of solace in the colour blue and its connections to melancholy and magic, which is where I’m comfortable. I don’t dislike yellow. I love the colour, but it has those associations for me.

Let me stay inside the trope of natural growth to ask if there’s a natural place for you to go, or a direction in which you can grow? You’re making work and you’re exhibiting widely, but do you see something in the future that you want to do?

I’m working on a series that is more figurative and that straddles the “Eunuch Tapestries” and the works where I’m morphing body and land but in an even more experimental way. I can’t articulate it better than that. It’s difficult for me to say where I’m going because I often have eureka moments in the act of doing. I’m not thinking about it when I’m in the midst of doing it. Sometimes you have to be months beyond something before you can fully articulate what you’re doing. For someone who works with text and writing, perhaps that doesn’t make any sense.

One final observation. A group of artists that I see in relation to your work is the Pre-Raphaelites. They were interested in a democracy of components, so that everything in one of their canvases has the same value. Even though they’re the most detailed literal painters, in this regard their works are abstract.

I’m astonished when I’m in front of a Pre-Raphaelite painting. Yes, that is utterly important. Actually, the person who ingrained that in my brain was Alison Norlen. I can’t remember exactly what painting I was having trouble with, but it was figurative and it was not working. Alison said, “You are focusing on this focal point, which is the body, but everything else is falling apart around it. You have to pay prime attention to everything in this work for it not to collapse. If that means that the background is completely delineated by the shadow, then that shadow has to be considered exactly the way the body was.” And that’s something I absolutely adore about the Pre-Raphaelites. Or someone like Caravaggio. Before I had seen his works in person, they were about the volume of incredible bodies bathed in light and their sense of space in this Baroque blackness. But seeing them up close in Ottawa at the National Gallery was so remarkable because you get a sense of his attention to detail in these black spaces, which are filled with little critters and with flowers. So now I obsess over the corners of illuminated manuscripts or medieval to early Renaissance paintings where figuration is front and centre, but in the foreground are all these remarkable depictions of thistles and lilies, all of which have their own meaning and place. ❚