“The Way To Always Dance” by Gertrude Story

Gertrude Story’s The Way to Always Dance is a disturbing book. There is more intensity and undiluted meaning in these short 130 pages than there is in most 500-page blockbusters. The nine stories in the book, written almost in shorthand, progress chronologically to form a short novel. It is a terrific story, and well told.

Ms. Story seems to have chosen to write in raw bursts of energy. She tells Alvena Shroeder’s story in the spirit of a farm woman, uneducated but passionate, naive but resourceful, who is forced by fear and circumstances to suffer alone. By consciously limiting herself to the heart of experience, Ms. Story’s narrative gains considerable depth and intensity. She lets the events in Alvena’s life speak for themselves.

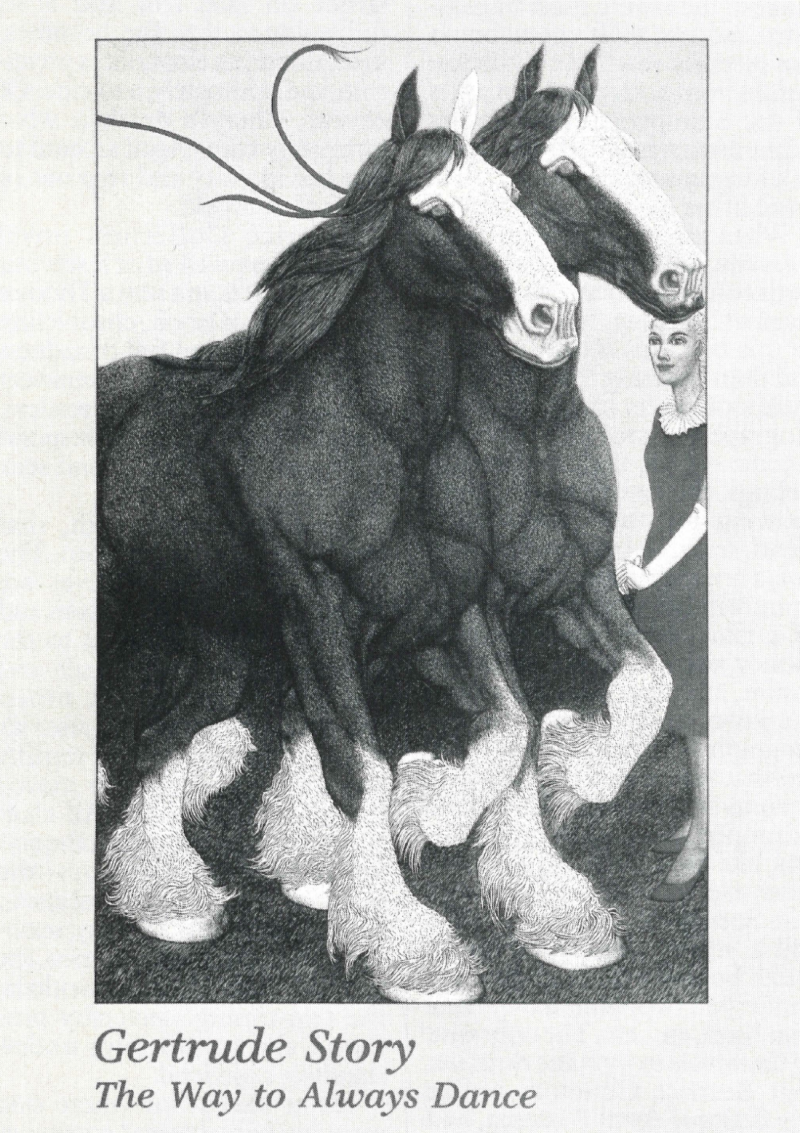

To do this, she shifts back and forth freely from first to second to third person, so that the voice of the book is never clearly Alvena’s or the narrator’s. Much as a storyteller would, she uses repetition of the wild geese, of David’s twinkling toes, to heighten the dramatic effect. (It is important to note that Ms. Story’s work has been broadcast on CBC, so perhaps part of the reason for her style comes out of a concern for how the phrases sound, as much as how they read.) She sketches startling images, of the father on his knees in the warm dusty barn, of Alvena plowing fields with a team of Clydesdales and the ghost of her true love by her side, of Alvena’s work-reddened hands hidden by white gloves. The descriptions of farm life in the past are brief, but provide the necessary scenery for the ride through the book.

Story’s chief intention is to communicate the lessons Alvena has learned from life and the spiritual sacrifices she has had to make along the way in order to survive. She captures difficult spiritual and emotional states in simple language, as if she were the literary equivalent of a primitive painter. She refers often to “power eyes” and to Alvena’s imagination as “the place where the pictures are.” The tone is consistently intense, riding the crest from one crisis to another.

If Alvena were a contemporary urban heroine, she might have tried to find herself a good therapist, or at least someone she could trust to tell about the strange flowing lights she sees while lying awake in bed at night. It would be nice if someone had been understanding or knowledgeable enough to point out to Alvena that there are solutions to heartbreak and isolation, even to madness. However, it is dangerous to trust anybody when you think you’re going crazy, and Alvena is too frightened and too proud to turn outside for help. She relies totally on her inner resources, and in the last story, when she is fifty and in bed alone with a fever, they come through for her, and she finally overcomes.

How does Alvena’s experience relate to urbanites preoccupied with pay TV, video cassette recorders, home computers, nuclear weaponry, movie special effects and other forms of electronic wizardry? The answer is clear. All those things are diversions. People haven’t changed. Even in Advanced Technological Societies (ATSes?), people suffer alone. Alvena’s experience is universal and timeless. What she needs is love and trust, commodities that are as scarce today as they were in rural Saskatchewan in the 30s and 40s. Yet she survives without them, at a price, like a tree with half its branches lopped off.

This is a wise story, written as if the author had never read another book, but had a great deal to say and was bound and determined to say it in her own original way. However unconventionally told, the book has a unity and strength that holds it tightly together. Ms. Story is at times excessively urgent in her efforts to communicate Alvena’s painfully distilled wisdom, and almost lectures the reader about her important discoveries.

Alvena’s suffering is composed of elements common to universal womanhood, stemming as it does from the loss of a beloved man, her own gullibility and a life wasted at low-paid work. Usually, pride and discretion keep women’s agony under the table, but occasionally it cracks through the polished surface in full force. Ms. Story has given us such a tale, at once cautionary and shattering.

The book has been beautifully produced by Thistledown Press of Saskatoon, with an apt cover illustration by Marie Elyse St. George. ■

Melinda McCracken, who reviewed Night Travellers in Vol. 2, No. 3, is working on a novel.