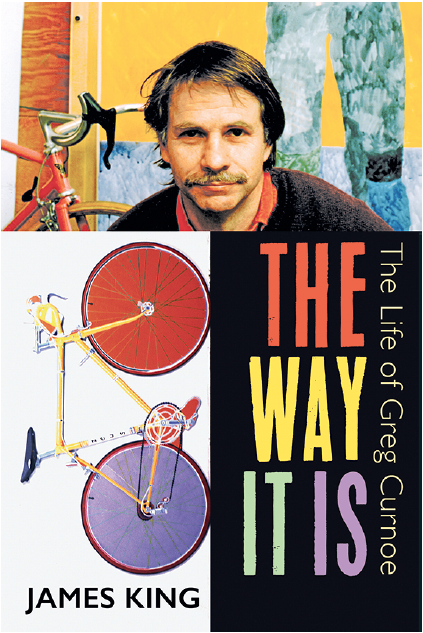

The Way It Is: “The Life of Greg Curnoe” by James King

The Way It Is: The Life of Greg Curnoe by James King, Dundurn Press, 2017. Courtesy Dundurn Press.

When he was knocked off his bicycle on the highway and killed by a pickup truck in 1992, Greg Curnoe had already established himself as an idiosyncratic artist with a unique pop/conceptualist/ Dada voice, a pioneer in what was to become the ultra-hip genre of experimental Noise music. He was also an outspoken political figure in the areas of artists’ rights and radical regionalism— having co-founded CARFAC and steadfastly maintained his base of operations in his hometown of London, Ontario, for just shy of 56 years. As well, he had only recently begun to emerge from a period when his new work—contemplative, relatively traditionally figurative and executed in the perennially unfashionable medium of watercolour—was being misunderstood and labelled “irrelevant” by the art-world establishment.

It’s a narrative arc that reads like a roller coaster breaking down just before the final payoff plunge, leaving everyone to be laboriously shuttled to the ground via some giant, clunky, mechanical cherry picker. There’s something akin to this at work in The Way It Is: The Life of Greg Curnoe, the recently published biography by James King, whose previous books have profiled William Blake, David Milne, Lawren Harris and Herbert Read.

With Curnoe as his subject, King starts strong—building from a patchwork of sources a colourful and engaging portrait of the artist (and provocateur) as a young man, following his rising star as a singular emerging talent in the early ’60s Canadian art world, and his ultimate renown as an enfant terrible pop artist with an anti-authoritarian axe to grind.

This is the cartoon version, of course—Curnoe’s art was a unique and complex amalgam of exquisite modernist formalism, legitimately acquired vernacular cultural borrowings and avant-garde literary experiments. His political positions were similarly convoluted beneath the hard lines and flat colours of their surfaces.

King, while clearly less than 100 per cent sympathetic to Curnoe’s anarchistic tendencies, manages to convey their depth and nuance through an abundance of detail and a variety of testimonial voices. Probably the most poignant example is the account of the artist’s tragicomic experience producing Homage to the R34, a mural commissioned by the Department of Transport for the Montreal International Airport in Dorval, Quebec, in 1968.

At over 32 metres in length, Homage to the R34 was the largest work Curnoe ever created. Ostensibly depicting the gondolas from the titular British dirigible in actual size, the gargantuan array of shaped steel and plywood panels formed the structure for a virtuosic stream-of-consciousness mash-up of autobiographical, historical and contemporary cultural commentary rendered in Curnoe’s high signature style.

Flat geometric sections of bright, saturated colour establish a sequential structure and a deceptively cheerful tone. Interspersed across the composition—looking out from the gondola portals—are portraits of a variety of unlikely passengers, including Curnoe’s wife, Sheila, and son, Owen, their Manx cat, Jesse, a grab bag of his London friends, Métis leader Louis Riel, “mad bomber” Paul Joseph Chartier (who died trying to blow up the House of Commons in 1966) and a figure many interpreted as then-POTUS Lyndon Johnson, plummeting earthward as his hand is severed by a rotating propeller.

Adding insult to injury, Curnoe integrated examples of his trademark rubber-stamped text passages, mocking the recent decision to strip Nam draft-resisting Muhammed Ali of his heavyweight crown, recalling an encounter with obnoxious Yankee bar patrons at an Albert Ayler gig in Buffalo, quoting a first-hand account of a WWI German bombing of an English kindergarten and citing the Freedom Anarchist Weekly.

Unsurprisingly, the mostly American passengers deplaning in the International Terminal were not amused. A mixture of actual complaints and pre-emptive censorship resulted in the work’s being removed within a few days of its installation. The Department of Transport wanted Curnoe to create a less controversial replacement at his own expense, but the artist steadfastly refused.

King’s treatment of this incident mixes a thoroughly deadpan account of the unfolding events with a mildly disapproving commentary on Curnoe’s “arrogance”—while nevertheless identifying the work itself as the culmination of his recent breakthroughs, and comparing it to Diego Rivera’s obliterated 1933 Man at the Crossroads mural. This contradictory mixture of hagiography, crankiness and quotidian detail results in an artist’s biography that is strangely analogous to the subject’s own personality and artistic MO— and seems particularly suited to Curnoe’s later years, when he turned away from overt references to mass media and commercial graphics in favour of a handmade aesthetics of intimate autobiography.

Printed entirely on glossy paper, with copious high-quality reproductions, The Way It Is may not be the final word on Curnoe’s legacy, but it stands alongside the Art Gallery of Ontario’s 2001 catalogue Greg Curnoe: Life & Stuff, George Bowering’s The Moustache, Judith Rodger’s pithy (and freely downloadable) Life & Work and Curnoe’s own writings as an essential piece in the puzzle of one of the most innovative and engaging artists of the late 20th century, and the mystery of what that missing third act might have unleashed. ❚

The Way It Is: The Life of Greg Curnoe by James King, Dundurn Press, 2017, 392 pages, $45.

Doug Harvey is an artist, writer, curator, educator and experimental musician living and working in Los Angeles, and is a founding member of the Student Bolsheviks art collective.