“The Warblers”

A Martian walks into an art gallery. Very soon it comes face to face with one of the portrait-like paintings in Sandra Meigs’s and Christopher Butterfield’s “The Warblers” and laughs out loud. What’s funny? The alien’s laughter might have been provoked by a reversal of expectations about what human beings really look like. Humans looking at the cartoony heads, which are trying hard to seduce them, might share in the laugh. Some viewers did laugh, but others felt sad. “The Warblers,” a series of 10 paintings by Meigs, accompanied by low-key cacophonous sound by composer Butterfield that filled the gallery like an atmosphere, could go either way. “The Warblers,” 2021, like most of Meigs’s serio-comic work, held up a mirror to a viewer’s state of mind and emotions.

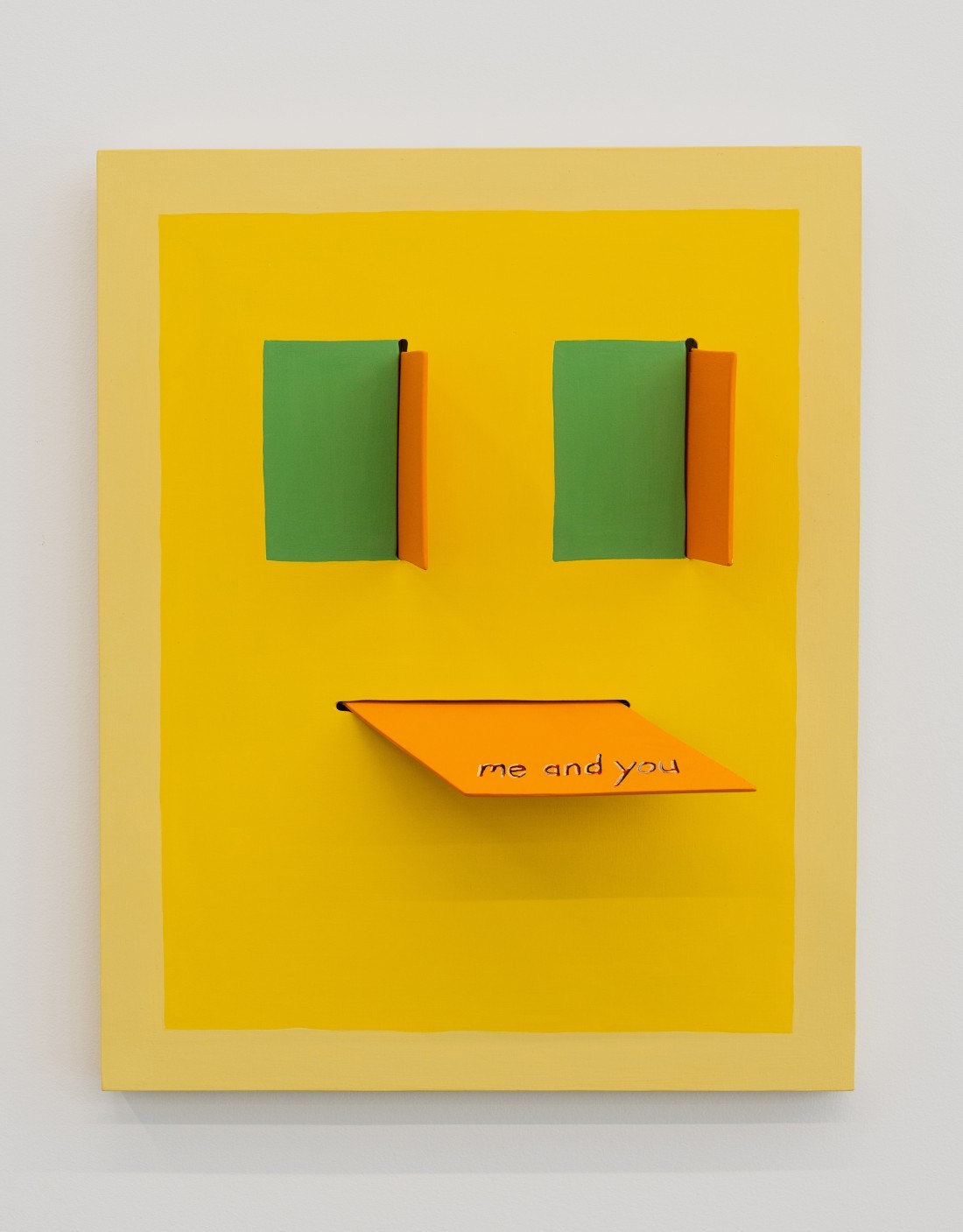

The paintings on vertical wood panels make “portrait head” an almost literal term as the head and face are synonymous with the painted three-dimensional object. Each head contains three rudimentary facial features—two eyes and a mouth—that are, in fact, protruding flaps hung on horizontal wires set into slits in a field of delectable colour surrounded by a border of lighter or contrasting hue. The border suggests a frame, but “The Warblers” are not representations of something, as in illusionistic painting. They are something: automata with personalities who display a certain amount of agency. They speak via words written on their “tongues” as though they were trying to strike up a relationship with their viewers. And it is their individual attentionseeking voices, all talking at the same time, that make Butterfield’s clamouring soundscape a babble of songs.

Sandra Meigs and Christopher Butterfield, me and you, from The Warblers, 2021, enamel on panel, wood, piano wire, audio box with motorized bells, 20 x 16 inches. Photos: Kelly Hofer. Courtesy VIVIANEART, Calgary.

Sandra Meigs and Christopher Butterfield, installation view, “The Warblers,” 2022.

Warblers in nature are small, active, brightly coloured birds known for their song, which trills and quavers. The tinkle and thunk of the warblers’ songs in the art gallery issued from jingle bells mounted on piano wires attached to the outside of audio boxes hanging above each of Meigs’s paintings. Motors inside the alarm-red boxes rotated the piano wires, which were bent into varied shapes to hold bells of different sizes. Instead of an animated jingling, the bells produced the warblers’ voices as rising and falling rhythms. Each warbler in the disharmonious chorus sang a song tailored for its character that, when you stood in front of it, could be distinguished from the ensemble sound.

The whole of “The Warblers” was made with the kind of ingenious simplicity and economy of means that produced complex results, which only accomplished artists like Meigs and Butterfield can pull off. The heads, especially, drew on feelings that living in pandemicinduced isolation has engendered: malaise, a sense of suspended time, languishing, loneliness and longing for human contact. The handprinted words on the tips of the warblers’ tongues say Hi, Ask Me Out, Please, Hold Me, Stay, Kiss Me, Call Me. Meigs’s paintings have the visual aura of an adolescent girl’s art project coupled with adult desire. Butterfield’s musical automata speak to found objects, simple mechanics and DIY agency. The smallest details of “The Warblers” were nuanced. A slight bend in a piano wire changed the tone of a voice; a change in the size or angle of a flap altered the expression of a face. The flaps recall the shutters or vents of architecture and machines; the faces are facades. Metaphorically, “The Warblers” are shut-ins.

Meigs began the project early in the pandemic during total lockdown, going only to the studio where she also was alone. The paintings kept her company, she says. When she began to see them as a series, she emailed Butterfield. Meigs gave him the work’s title, told him that the paintings “talked” and asked if he would like to accompany them with sound. She sent along some inprogress images and gave him carte blanche. They worked in parallel with very little consultation. Butterfield supplied the bells from jingles he had picked up over the years and Meigs made the audio boxes.

The two, who were colleagues at the University of Victoria before Meigs moved to Hamilton, Ontario, have worked together since 2010 on several projects that combine visual art and sound. The first of these was Butterfield’s operatic setting of Jacques Prévert’s complete contes pour enfants pas sages, for which Meigs created the projected illustrations. He devised the clack and hum issuing from the six shrouded, life-size, whirling automata in Meigs’s installation The Bones in Golden Robes, 2013, a profound embodiment of grief. He conceived the everchanging tonal soundscape for Meigs’s complex installation Room for Mystics, 2017, 30 large, freestanding metaphysical abstractions laid out in a maze underneath a huge red mobile that signified a beatific face with just two rows of curved eyelashes and a wide u-shaped smile.

“The Warblers” present themselves as cheerful, flirty and desperate for attention, all at the same time. As automata, they are going through the motions of human life, to which they refer, but they elicit poignant feelings through cartoony characters, the more so because they are so unreal. Hyperreal automata can be alienating, threatening. The cartoonish aspect of “The Warblers” distances the human emotion and brings it home through exaggeration. Meigs takes things further when she says, “‘The Warblers’ embody what a painting wants,” that they are paintings about paintings. Theorist WJT Mitchell posed the question “What Do Pictures ‘Really’ Want?” in October magazine in 1996. “Pictures want equal rights with language, not to be turned into language,” he wrote. They want “to be seen as complex individuals occupying multiple subject positions and identities.” Then he takes things further to suggest that it might be better to model the desires of pictures on the non-human, another choice being the machine. Human, automaton or painting—in the end, the desire of “The Warblers” is much the same. Isn’t this what we all want? To be paid attention to, to be seen and to be loved for who and what we are? ❚

“The Warblers” was exhibited at VivianeArt, Calgary, from February 26, 2022, to April 14, 2022.

Nancy Tousley, recipient of the Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts, is an art critic, writer and independent curator based in Calgary.