“The State”

Canada’s sesquicentennial is nearly upon us. Its immanent arrival has been marked by the circulation of specific terms and images used by our own government to convey state-sponsored concepts of nationalism, not to mention an influx of funds for the realization of celebratory public works. This kind of posturing compels larger inquiries into what implications colonial celebrations have on our interpretations of the nation state, specifically within the arts, wherein new grating opportunities are supporting the creation of projects that focus on Canada’s 150th anniversary. Plug In ICA’s recent exhibition “The State,” featuring photo and installation works by Vahap Avṣar, Maryam Jafri, Christian Jankowski and Duane Linklater, skilfully mines these very conceptions of nationhood.

“The State” is able to reveal the kind of standardized, almost predictable, pomp and hubris used by governments to naturalize and endorse the modern nation state. All the artworks in the exhibition respond to or critique official devices of nationalistic representation, including those in the form of documents, monuments and photographs. But what makes these recontextualizations of the archive so effective is that several of the works within the exhibition point to current issues related to movements of resurgent nationalism. Vahap Avṣar’s Lost Shadows presents a series of potentially propagandistic postcards produced by the Turkish printer AND Postcard Company in the 1970s, depicting various tourist sites, public gatherings, ceremonies and scenic views. The photographs commissioned by the printer were acquired by the artist in 2010 and were presented within the exhibition as a set of 12 takeaways, none of which had been previously circulated. As Jennifer Papararo notes in her curatorial text, “In one image there is a white car pulled off on the side of a mountain road disrupting an otherwise idyllic vista. The model of car, a white Renault 12, was commonly used by the Turkish secret service, and alludes to a control that was building and visibly present after a military coup in 1980.” This and other images in the series seem to take on new meaning when seen as a backdrop to the recent failed coup in Turkey and the resultant pro-government actions taken in Istanbul and elsewhere.

Christian Jankowsi, Heavy Weight History, 2013. All images courtesy Plug In ICA, Winnipeg.

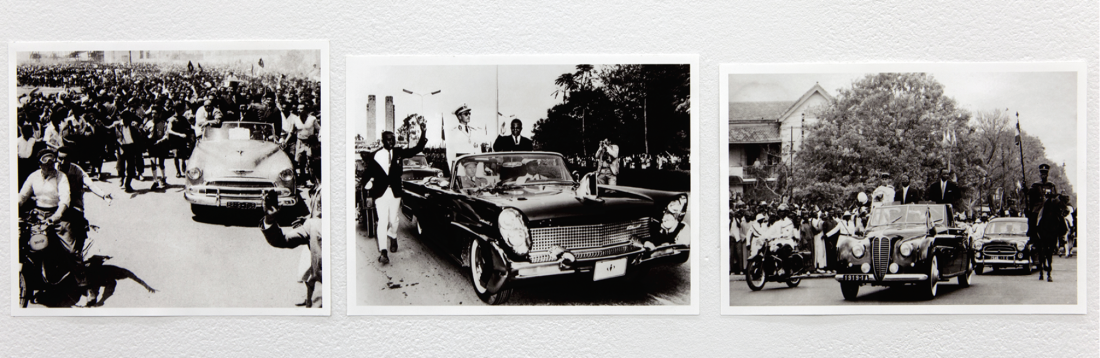

Similarly, Maryam Jafri’s Independence Day 1934-1975, 2009–ongoing, makes visible black and white archival images of the new governments marking their independence from colonial rule, while in several images, hosting British dignitaries. It becomes almost ironic given some of the political and social impetuses underlying Brexit. Jafri’s artist’s statement explains, “The first Independence Day, leading up to and including the formal ceremony, unfolds as a series of highly codified rituals and elaborate speeches enacted across public and elite spaces. The swearing in of a new leadership, the signing of relevant documents, the VIP parade, the stadium salute, the first address to the new nation, is all supervised and orchestrated by the departing colonial power.” These kinds of parallels between past events and present-day political climates seem to rebuke neoliberal conceptions that globalized economies will defeat the weight of history. “The State” offers a critical and well-timed response to how the rendering of official histories can be repositioned but also measured against current political leanings, especially in the context of nationalistically tinged populist movements dominating this past year’s news headlines.

Weight becomes a literal concern in Christian Jankowski’s Heavy Weight History, 2013. The video follows 11 members of Poland’s weightlifting team as they attempt to lift various Warsaw-based monuments. Jankowski hired the team to flex their muscles on a range of statues, including those celebrating Polish/Soviet relations, the famed The Mermaid of Warsaw sculpture and a massive bronze bust of Ronald Reagan. Played out with all the production trappings of televised sports, Heavy Weight History is hosted by a well-known sports announcer and features interviews with team members and slow motion replays and closeups of the uniformed athletes as they epically succeed and fail at elevating a total of seven historical markers. The comical, tongue-in-cheek video, which is accompanied by bleacher-like seating, takes a pragmatic approach to history. Watching the weightlifters struggle with some of the sculptures and hearing them comment about others simply being too heavy to lift makes clear that certain pasts are more easily forgotten or passed over than others. The inability to uproot particular monuments further speaks to how deeply implanted, both physically and psychologically, these custodians of history can become, and how difficult it is to unseat them from their post as watchdogs over our collective memories.

Maryam Jafri, Independence Day 1934–1975, 2009–ongoing.

Duane Linklater’s installation border, 2016, is the only one in the exhibition that directly looks to Canadian and Indigenous history. Combining images with draped materials, including textiles and plastic sheets, the large-scale sculptural assemblages occupied the back wall of the exhibition. To the far right, somewhat hidden between a tapestry of pink fabric and clear plastic, Linklater displayed two letters dating to 1999 that identify his paternal heritage as being “100% Native American.” The letters are signed by band chiefs from Fort Albany and Weenusk First Nation. According to Papararo’s text, these documents confirm that the artist is eligible under the Jay Treaty, which was established in 1794 between the United States and Britain to encourage better trade and border relations. One of the agreement’s provisions somewhat acknowledges precolonial conditions and allows Indigenous communities to move freely across the border and remain exempt from certain duties. The US government recognizes this treaty for those whose blood tests and ancestral lineages prove them to be at least 50% Indigenous, while the Canadian government in no way supports the agreement. In 2001 the Supreme Court of Canada went so far as to rule that the right to cross the border without paying duty is not an “Aboriginal right.”

Another of Linklater’s wall works, body, 2016, combines a poster version of Norval Morrisseau’s Untitled (Shaman Traveller to Other Worlds for Blessings), 2009, with a sizeable textile featuring a happy poppy motif. Coup, 2016, likewise merges a stack of images of the artist with Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty fitted amongst loosely formed draperies. Linklater’s work stands apart in some ways. Perhaps this is owing to his project being less overt in its use of source materials. Or perhaps it is because he is the only artist in the exhibition to directly implicate himself in depictions of statehood. Either way, border refocuses the exhibition towards individual citizenship and reminds us that the ways in which nations represent themselves is not merely related to pageantry but rather to economic, political and social control. Nationalized projects may neatly conceive of the state but Linklater expertly stresses a more uneven and malleable picture, giving form to the complicated ways we navigate through our own national histories and images of place.

The artworks in The State effectively stress that “post-colonial” cannot function as accurate verbiage for any contemporary condition. Instead, each of the artists invokes the slippery nature of nation building that can only ever exist as a condition of both the past and present. The trauma of the 20th-century has imprinted on us a feeling of constantly tripping back into history. Avṣar, Jafri, Jankowski and Linklater’s works attend to this feeling while also making room for a nuanced dialogue about what it means to portray nationhood. ❚

“The State” was exhibited at Plug In ICA, Winnipeg, from July 1 to September 11, 2016.

Noa Bronstein is a writer and curator based in Toronto. She is currently the Executive Director of Gallery 44 Centre for Contemporary Photography.