The Shanghai Shuffle

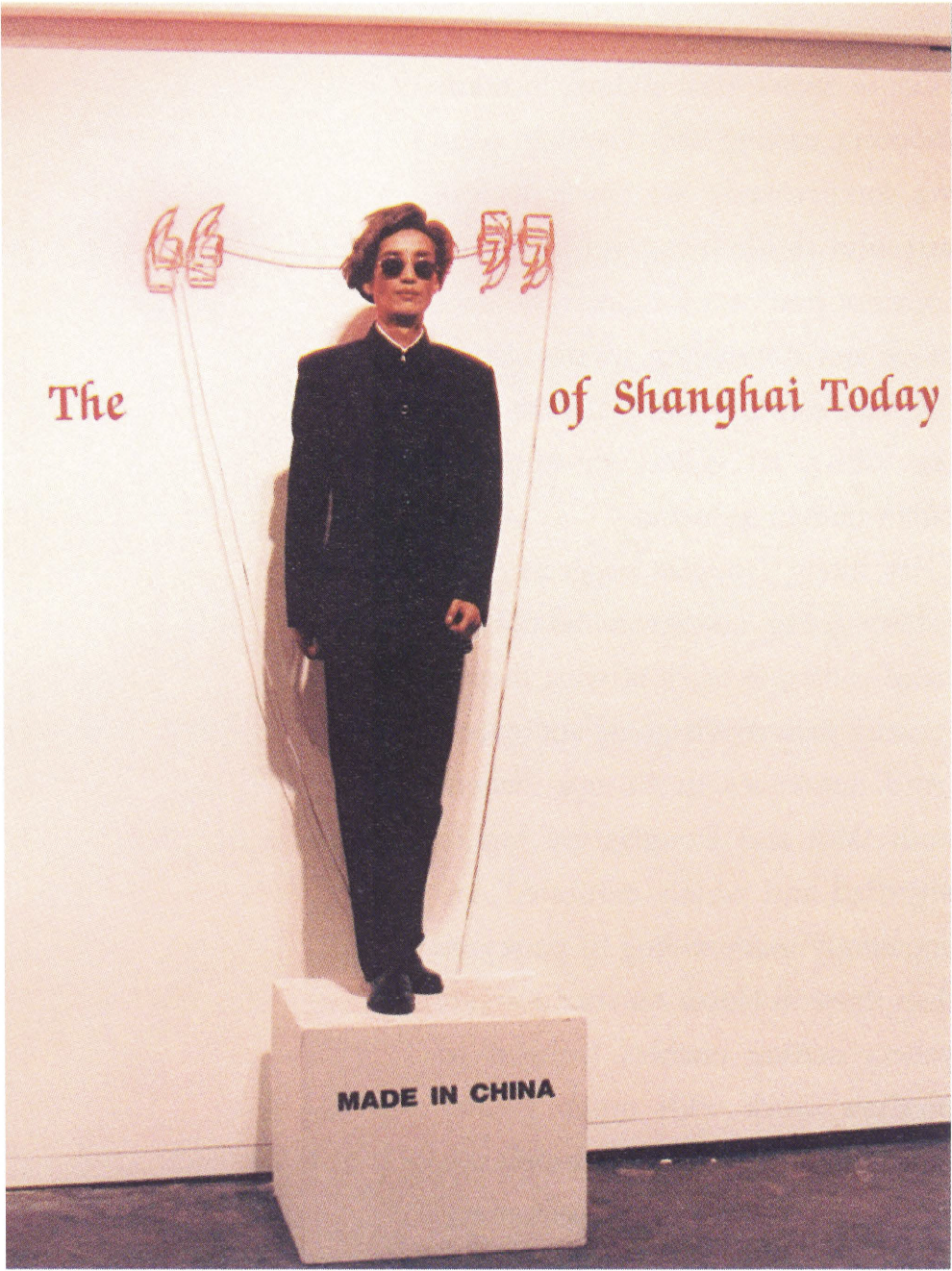

I lent my Polaroid camera to Shi Yong so that Plug In patrons could have their picture taken with him at the opening of “Looking Out/Looking In.” The artist was in perfect character the whole evening, standing stock straight on a pedestal as he formally shook hands for the camera. His expression was cool and Warholian, or was he just showing traditional Chinese politesse? He reminded me of the late 1970s photo performance artist Tseng Kwong Chi, who posed for similar photographs but in a Mao suit. Shi, like Tseng, was obviously being ironical but I kept asking myself—what wasn’t obviously unironical about his work and the art of his colleagues? Their longing to be Western artists has a paradoxical sincerity about it. To be ‘Western” is it necessary to be ironical, distanced and jaded?

In a darkened room Plug In calls the “anti-chamber,” Shi set up a chair next to a photograph of himself sitting in the same chair. The work is a direct quotation of Joseph Kosuth’s classic 1960s conceptual art piece in which a photostat of a dictionary definition of “chair” appears with a real chair and a photograph of it. Shi’s homage at once glamourized and memorialized the Kosuth work.

These artists did not learn how to be neo-conceptual artists at a California grad school but in the fluently international city of Shanghai, one of Communist China’s windows on the west. The former Chinese academic and current director of Art Beatus in Vancouver, Sheng Tian Zheng, assured viewers that official socialist realism still dominates the Chinese scene, and that “Looking Out/Looking In” is about relatively aberrant Chinese art. (I assume that we can expect a muscled worker illustration and a no irony installation later this year as the anniversary of the Chinese revolution is celebrated.)

At a symposium held in conjunction with the exhibition I asked the panelists whether the People’s Republic of China encourages and allows the export of its western-style avant-garde art for sophisticated political reasons. Not at all. Cool art is not encouraged in order to show China’s liberality the way the post-war American government once sponsored Abstract Expressionism in order to demonstrate to Cold War viewers “free expression in a free country.” Western concepts of individuality and freedom have never been Chinese values, chimed the panelists, and the artists in “Looking Out/Looking In” do not see themselves as engaging in “free expression.”

Shi Yong, The New Image of Shanghai Today, I999. Photograph Xia Wei. Courtesy:Tim Schouten.

Panelist Hank Bull felt that differences needed defending in such cross-cultural exchanges. As if to illustrate, Ding Yi answered a leading question from a Christian about the significance of the cross in his “Appearance of Crosses” paintings by avowing that the cross had absolutely no cultural meaning” for him. Later Tim Schouten, this show’s able curator, said that Ding Yi used loaded patterns such as Macintosh tartan fabric (loaded at least for Scots) in his paintings without concern for what a Macintosh tartan might “mean.” The choice was purely visual. Obviously Christianity and Scottishness have little to do with Ding Yi’s abstract art, but his denials of iconicity sounded enough like the denials of content uttered by Abstract Expressionists in the 1950s that the work dropped out of the Plug In mix; if his intention is to make purely formal art—and the Scottish ironies are not a send-up of abstract painting—then his work is inconsistent with his postmodern colleagues.

By contrast, when Zhou Tiehai fakes covers of mass-circulation magazines, putting his portrait front and centre, he means to be ironical. Zhou has also listed himself on the Shanghai stock exchange as a commodity. He collapses his work into its method of distribution—the publicity is the art and the work is the press release. The piece reminded me of New York artist Shaun Gough’s (so far unsuccessful) efforts to commission Coke to produce a Coke billboard at his expense, a project that, like Zhou Tiehai’s, marks the outer limit of the possibilities of capitalist appropriation. In these cases we measure an attempt to make a complete compromise with capitalism by assessing the degree of its failure.

Hu Jie Ming’s New Journey to the West ties an appropriated video (a costume drama full of grovelling gestures and slapstick buffoonery) to the scripted voices. It is a tale of the mythical green card at the end of a Chinese artist’s rainbow, another example of this exhibition’s underlying theme of how-to-win-the-west through the seductive techniques of what one might call the Shanghai shuffle. New Journey… is genuinely light-hearted and without the earnest ironies of much of the other work.

This exhibition makes me want to see more Shanghai Cool, but I’d also like to see some of that much-hated official social realist art—the type that can be read ironically without the artists laughing along. My guess is that contemporary Chinese socialist realism would give our wildlife artists a run for their money. ♦

“Looking Out/Looking In” was on exhibition at the Plug In Gallery in Winnipeg from January 6 to January 31, 1999.

Cliff Eyland is a painter who is represented in Toronto by the Leo Kamen Gallery.