The Otolith Group

Balance and instability, space, time, history and memory comprise the constantly shifting poles of the Otolith Group’s sprawling oeuvre, which includes film, writing, research and curatorial projects. Fittingly, the London-based media theorists and artists Anjalika Sagar and Kodwo Eshun have named their collaboration after a structure in the inner ear that transmits information to the brain, an organism that needs to keep itself balanced.

Taking its name from a Theosophist text by Annie Besant and C W Leadbeater, the group’s first large-scale museum exhibition, “Thoughtform,” at Museu d’art Contemporani de Barcelona incorporates diverse strains of history and media. Keeping with her perennial concern with “how thinking emerges through the substance of art,” curator Chus Martinez grapples admirably with the challenge of presenting archive- and research-driven work in a manner that an audience can synthesize without diluting its impact. She succeeds not only in spatially developing relationships among the group’s subtly intertwined body of concerns but also in offering a platform to further extend the discursive production that lies at the core of the Otolith Group’s working methods. As such, the exhibition is conceived as a “production centre,” and through exposing the decision-making process and conceptual, historical and narrative touchstones that contribute to the Otolith’s films, Martinez enables the Otolith’s different research initiatives to “reverberate” at their fullest capacity.

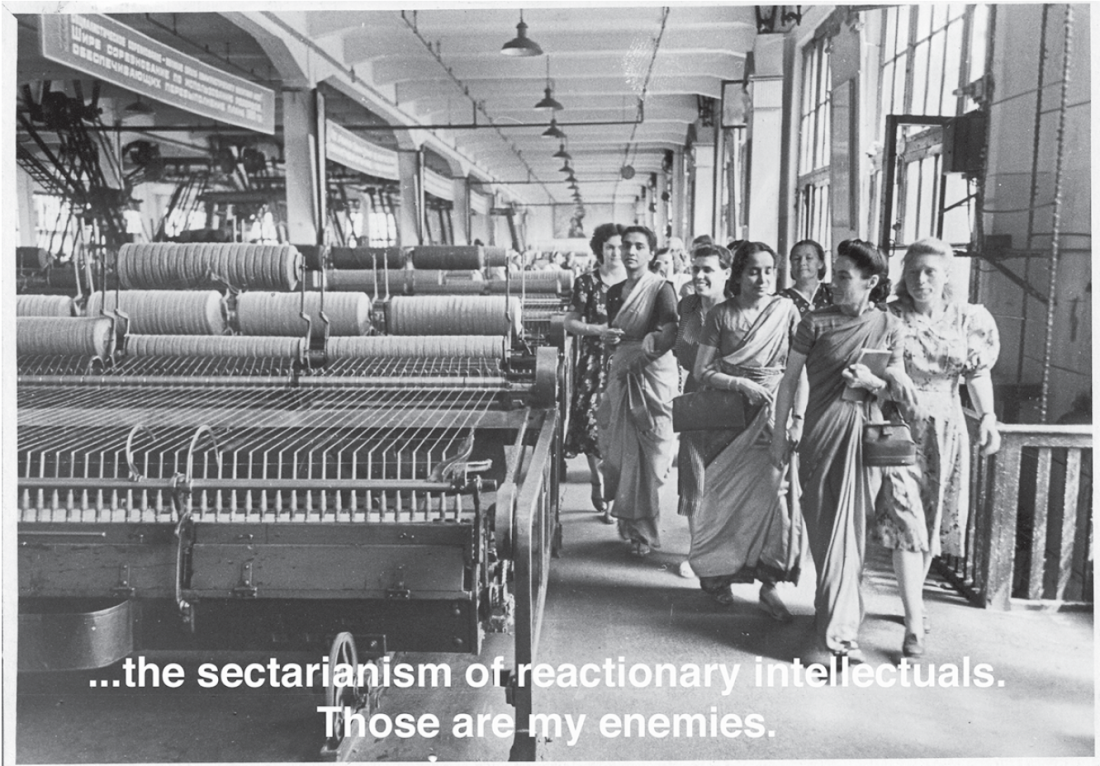

The Otolith Group, film still from Communists Like Us, 2006. Courtesy of The Otolith Group and LUX, London.

“Thoughtform” assembles the Otolith Group’s major works for the first time. In addition to their best-known work, the Otolith Trilogy, the exhibition at MACBA includes the newly commissioned Hydra Decapita as well as The Inner Time of Television, an installation that simultaneously screens 13 chapters of the acclaimed filmmaker Chris Marker’s 1989 television series The Owl’s Legacy. Entering the exhibition, viewers are greeted by 10 unremarkable pastel drawings and, after peering around the corner at the spare, archivally tinged projection, video and timeline that share the first exhibition hall, the unassuming pastels start to seem a bit bizarre. Step a little closer, however, and they offer the first thread to begin unravelling this densely layered exhibition: while the artist signed the work in the mid-’90s, the wall text reveals a different story.

With titles like Protocol Division and Biohazard Facility for the Visitation and dates ranging from 2013 to 2024, the works aver to be a commission on behalf of the so-called “Institute for Extraterrestrial Cultures,” revealing the Otolith’s penchant for the modalities of science fiction in a cleverly subtle disguise. Indeed, the aim of the time-travelling experiments in Chris Marker’s short film La Jetée provides valuable insight into how Kodwo and Sagar instrumentalize the tropes of science fiction in their work. For the Otoliths, images function as emissaries in time that “summon the past and the future to the aid of the present.”

The Otolith Group, film still from Otolith, 2003. Courtesy of The Otolith Group and LUX, London.

This idea of sending images as delegates into the future appears explicitly in the video Communists Like Us, a film that incorporates images from a trip to Maoist China by the National Federation of Indian Women—a group that included Sagar’s grandmother—paired with subtitles from Godard’s iconic agit-pop film, La Chinoise. Fictitious characters emerge alongside historical figures and lesser known, but nonetheless real, people throughout the works in “Thoughtform.” Anasuya Gyan-Chand (Sagar’s grandmother) and the Russian cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova appear several times in different works, as does Anjalika Sagar herself and Dr. Usha Aderaran-Sagar, a distant mutant relative from the future. In Otolith I, Aderaran-Sagar narrates the past via Anjalika Sagar’s archive, recounting not only meetings between Gyan-Chad and Tereshkova but also the pervasive sense of dread around the invasion of Iraq in 2003. Within the Otolith’s shifting, non-synchronous poles of history and memory, it can be difficult to discern fact from fiction, and in some ways the voice of the fictitious filmmaker in Otolith III, a film inspired by Satyajit Ray’s unmade 1967 film The Alien, is instructive for viewing the Otolith’s work in general. “For my movie to succeed,” the filmmaker says in a voiceover, “the actors need to undergo a great unlearning. They must listen to witnesses without proofs. To sound with no images. Stories without narrative. Memories without cause.”

Indeed, “Thoughtform” demands a manner of looking: a willingness to forget and to unlearn. States of suspended confusion elicit a porous relation to space and time. Despite the group’s roots in the political radicalism of the ’60s and ’70s era essay film, the exhibition’s dense amalgamation of films, illustrations, slideshows, pastels and sound works reveals an approach that is more dreamlike than didactic. Still, the Otolith’s approach to the notion of balance reveals its deep entrenchment in the experimental documentary tradition, focusing itself not on the even-keel of so-called “fair and balanced” information but on the interplay between the real and the imaginary, the historical and the fabricated, and the intellectual and the emotional. ❚

“Thoughtform” was exhibited at the Museu D’art Contemporani de Barcelona from February 4 to May 29, 2011.

Jesi Khadivi is a writer and curator living in Berlin where she co-directs the project space Garden Parachutes.