“The North End Revisited: Photographs by John Paskievich”

At a time when many in the arts are choosing to challenge the photograph’s uniquely indexical relationship to reality by producing visual versions of alternative facts, it is refreshing to see John Paskievich’s The North End Revisited, a book containing photographs characteristic of the kind of indisputable “factness” that until recently distinguished the photographic from all other imaging media. The book features almost 200 black and white photographs of people and places in that part of Winnipeg located east of the Red River and north of Portage Avenue where, in the 1950s and ’60s, Paskievich grew up as an immigrant child. The book also contains supporting essays by Stephen Osborne and George Melnyk, as well as an interview with Paskievich by Alison Gillmor. This is the third iteration of this work, with a far slimmer volume, A Place Not Our Own: North End Winnipeg, being published in 1978 and a further version, titled simply The North End, which appeared in 2007. Together with many images from the 1978 book, The North End included a number of new photographs, to which this latest offering now adds a further 80. Contrary to what one might expect, what results goes well beyond mere repetition, being instead a renewed response, a true revisiting in the way of an expanded and subtly nuanced dialogue with a longstanding acquaintance.

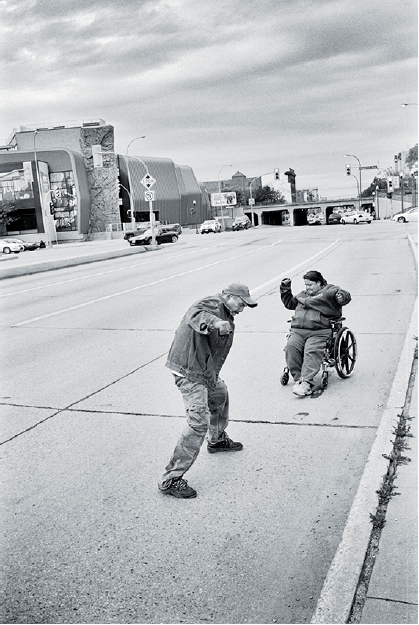

John Paskievich, Main Street and Higgins Avenue. Black and white photographs. Courtesy University of Manitoba Press.

While both the earlier books contained many excellent photographs, within the category of black and white photographic documentation or, more accurately, purported documentation, neither book was especially remarkable. They were each just one book among many that dealt with similar subject matter in similar ways. Time, though, has a way of changing everything, and in the last 10 years, let alone 40, little in the arts has been changed more by technological innovation than the understanding of photography: how it is perceived, practised and valued. Ultimately, it is this that makes this most recent expression of Paskievich’s work significant— not just the subject matter or the consistent intelligence of his image making—but the way his photographs and the book in which they are contained counter what the intersection between photography and art has come to mean.

In these days of casual, smartphone gestures, selfies and the contrived mise en scène productions of self-styled camera artists, Paskievich’s photographs and the manner of their presentation could easily seem old-fashioned, a throwback to those immediately pre-postmodern years of the 1970s when, in the West at least, the so-called straight photograph had become an art world darling; when photographers like Robert Frank, Garry Winogrand and Josef Koudelka were being hailed for their ability to transcend film’s stubborn documentary insistence by wresting meaning from the democratic renderings of seemingly ordinary photographs. Not surprisingly, Paskievich cites all of the above as influences, and this is certainly apparent throughout his work, slipping stylistically forth and back as it does between street photography, semi-formal portraiture and what I would call highly educated snapshots, all expressed within a photographic style suggestive of the documentary. Yet, Paskievich’s photographs are both less than that and more. While they do seem to fall, at first look, within the broad parameters of documentary, there are reasons to question the rigour of their conformity to that approach. For photographers consciously working in a documentary mode, image choices tend to become a contest between the kind of dispassionately complete rendering that documentation requires and aesthetics. For photographers who consider themselves artists, it is almost always the latter that wins out.

Higgins Avenue at Main Street.

Lorne Avenue at Austin Street.

Paskievich is well aware of this, even going so far, in the course of Gillmor’s carefully considered and perceptive interview, as to minimize documentary intention. Instead, he describes documentation as being only one factor affecting his primary goal, which is to make an interesting photograph, meaning, one must presume, a rendering that conforms to a kind of established pictorial or aesthetic standard. Achieving this photographically has traditionally involved carving timespecific chunks out of the universal continuum, never an easy task, especially when the photographer’s main focus is people living their lives and interacting with their environment. Inevitably, the intrusions of potential narrative and the random dispositions of an unruly world conspire to threaten pictorial intent. It is a credit to Paskievich’s ability that so many of his images retain a substantial proportion of their documentary relevance while simultaneously succeeding as aesthetically satisfying objects; a feat greatly aided by viewer acceptance of his photographs as having a direct and unmanipulated linkage to their origins—as being true representations. The other and more obvious indication that Paskievich doesn’t have an overriding commitment to the documentary process, however, is the titling, which ranges from the barely adequate to the wholly redundant.

Identifying specific sites and providing the location in the form of street names would be a minimum documentary gesture; however, without dates, not even the year in which a photograph was made, it becomes a challenge for the viewer to interpret the content and set it within a larger social, political or historical context. Titles like Man leaning against tree or A man filming in the snow, when associated with photographs that show precisely those things, are entirely superfluous.

These are relatively minor concerns, though—more observations than criticism—for what truly matters here is not so much individual photographs but their collective effect: how, together with the aforementioned interview and the essential context provided by the Melnyk and Osborne essays, Paskievich’s book evidences the evolution of an admirably enduring relationship between a man and a place. Such long-term commitments have always called for more than just persistence; for an artist, they also require considerable courage. This is especially so today when an artist’s success increasingly demands the unceasing production of the fresh and the new. Too often it seems that the sparkly simplicity of a surface skim rather than the shaded complexity of the deep dive The North End Revisited so obviously represents is what is expected. In that regard, I would suggest that, more than those he cites as influences, Paskievich’s true commonality lies with the likes of Eugène Atget, Fred Herzog and Itchiku Kubota, artists who, throughout their lives, and to similar effect, relentlessly focused upon an intense exploration of a particular singularity. ❚

The North End Revisted: Photographs by John Paskievich, University of Manitoba Press, 248 pages, paper, $39.95.

Richard Holden is a photographer and writer who lives in Winnipeg.