The Montréal Biennale: L’avenir (looking forward)

A compelling hallmark of this Biennale was its title, theme and perhaps its teleology, if finding a coherent teleology underlying most or all the work exhibited could be justified. “L’avenir,” the French half of the bilingual title, is an idea developed by French philosopher Jacques Derrida. Literally translated as “future,” Derrida employed the term to identify the uncertain character of what is to come. Who has not felt a certain frisson when listening to what Derrida says in the voice-over for the Kirby Dick & Amy Ziering Kofman documentary Derrida: “In general, I try to distinguish between what one calls the future and ‘l’avenir.’ The future is that which—tomorrow, later, next century—will be. There is a future that is predictable, programmed, scheduled, forseeable. But there is a future, l’avenir (to come) which refers to someone who comes whose arrival is totally unexpected. For me, that is the real future.” Similarly, in the works presented here the ‘real’ future—that is, the well-imagined future—is that which is repletely unpredictable and unexpected, the Other who arrives on my doorstep without my being able to anticipate the time or tenor of the arrival. So if there is a real future beyond this other known future, it is “l’avenir” in the sense of the coming of the Other, which I am unable to foresee.

Althea Thauberger, still from Preuzmimo Benčić, 2013–2014, digital film, 57:14 minutes. Photograph: Milica Czerny Urban. Courtesy the artist, Musagetes and Susan Hobbs Gallery, Toronto.

For the most part, the works in this exhibition shared an immanent spirit of progressive and retrospective critique. However, some took, as might be expected, a very dark and dystopian turn. This meeting with an unnamed Other certainly applied to, and achieved resonance in, some of the most salient and unsettling works in this vast exhibition.

One such standout was Kelly Richardson’s magisterial Orion Tide, 2014, installed not at the MAC (where it arguably should have been) but at a satellite outpost—the Quartier de l’innovation on Peel Street in downtown Montreal. This new two-channel video installation was immensely moving. It showed a vast apocalyptic desert landscape at twilight from which seedpod spaceships erupt like missiles, seemingly out of the husk of the earth itself one after another, into the sky. As I stood transfixed in front of it, I thought involuntarily of the Rapture, wholesale Terran exodus, the arrival of aliens, Christopher Nolans’s Interstellar. It segued so much with what we think about the future, since everything we think is so obviously speculative, and so often wrong even when most well-informed, and thus this artist beautifully incarnated Derrida’s remarks concerning the arrival (or departure) of someone or something totally unexpected and quite beyond our ken.

Equally enticing, and worth the price of admission in its own right, was Ann Lislegaard’s brilliant and evocative sci-fi opus Time Machine, 2011, at the MAC. This work invoked HG Wells’s novel of the same name. Here, a computer-animated ‘glitch’ fox—the glitch endowing it with an endearing stutter and visual instability—tells us of his visit to some future tense. It is not easy to make out his itinerary. It is as though he has been subjected to some temporal or spatial radioactive warping. An abiding strangeness effortlessly brings Derrida’s words to mind: here is the future lying in wait but one we cannot foresee. I would argue that this work, along with Kelly Richardson’s, set the auratic mood for the whole Biennale, with its emphasis on critique.

Lynne Marsh’s trenchant analysis of the still uncertain European geographic and political climate, Anna and the Tower, 2014, at Arsenal art contemporain, shows an air traffic controller at the Magdeburg-Cochstedt international airfield. Filmed on location at this still-idle former Russian airbase about two hours from Berlin, with the control tower as proscenium stage, protagonist Anna delivers sundry air-to-ground instructions and commands in a scripted performance in extensia and by rote. She seems frozen in time between an inertial now and a future that has still to unfold.

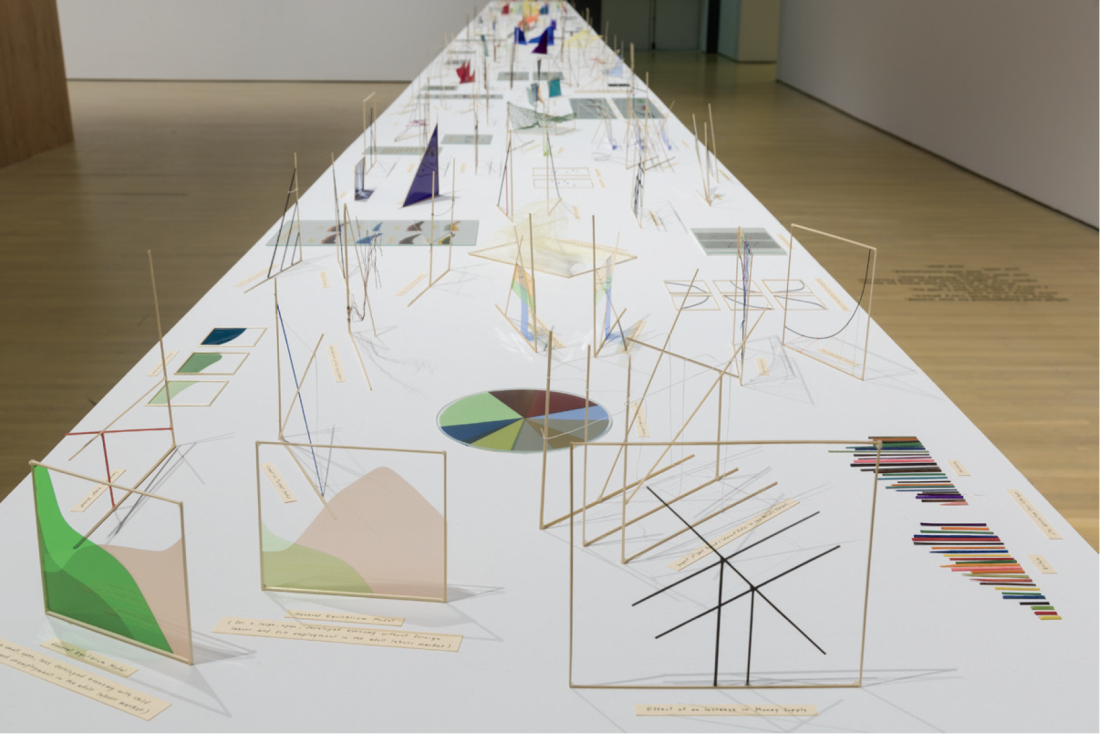

Richard Ibghy and Marilou Lemmens, The Prophets, 2013–2014, installation view, mixed media, table, 125 x 1300 x 81 cm. Photograph: Guy L’Heureux/La Biennale de Montréal. Courtesy the artists.

One of the most powerful—and unavoidable, given its visibility—installations was Krysztof Wodiczko’s video, Homeless Projection: Place des Arts, 2014, which projected homeless people outdoors onto the upper reaches of the buildings of Place des Arts. This powerful inditement of inequality and impoverishment was a clarion call that also sounded the exhibition’s preoccupation with critique.

Another unforgettable contribution to the exhibition was the North American premiere of the latest film by well-known Iranian-born American artist and filmmaker Shirin Neshat, at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Entitled Illusions & Mirrors and shot in 2013, it stars the Israeli-American actress Natalie Portman, whose performance was luminous and moving. The installation had an oneiric atmosphere, as we were led through a labyrinthine and haunting reverie, following actress Portman as she pursues a man—or the memory or precognition of one—across a blurry beach and into a mansion where shadows of the past, or actual people, or people yet to be born, await.

Known for her trenchant socio-political critique, Emmanuelle Léonard’s video Postcard from Bexhill-on-Sea, 2014, showed empty beaches at the British resort town while a voice-over from elderly residents and visitors was riddled with wistful regret for a past long since lost, even where inflected with a truly adult dose of racist and fascistic maunderings. Here, Léonard the wily ethnographer works her magic and pushes the envelope of retrospective critique using the real-world words of indigenous dwellers in Bexhill-on-Sea. In her other work in the Biennale, La Providence, 2014, Léonard interviewed, to moving effect, retired members of Montreal’s sisterhood of Grey Nuns—with the ever present promise of imminent death hovering somewhere in the foreground.

Isabelle Hayeur’s video and photoworks of post-Katrina New Orleans offered the yin to Leonard’s yang with a devastating analysis of American domestic policy concerning the aftermath of the hurricane which wreaked such havoc on the city. It was rife with wounds still untreated and unhealed. Hayeur shows images of the Louisiana shoreline that in themselves prophesize a very bleak future for this region on account of accelerating climate change and government apathy. The Bayou Terrebonne images are particularly compelling.

Abbas Akhavan, Fatigues, detail, 2014, taxidermy animals (American red fox, screech owl, northern flicker, white-tailed deer, red-eyed vireo, North American porcupine, Nashville warbler, Blackburnian warbler) and education activity. Courtesy the artist, The Third Line, Dubai and Galeri Mana, Istanbul.

Richard Ibghy and Marilou Lemmens’s The Prophets, 2014, at the MAC, an over-the-top installation of more than 400 tiny sculptures based on graphs and charts taken from economics journals and other sources, presented a voluminous, quirky and vastly distracting dilation on the future of labour and industry. The 13-metre-long table replete with fragile models (that seem to subvert the ‘authority’ of the data presented) is an incisive assessment of sundry economic models while offering, through art—panacea, divertissement and creative dovetailing. Their other project in the Biennale, The Golden USB, 2014, exhibited at VOX, centre de l’image contemporaine, is like a time capsule inspired by the Golden Record that was included in the inventory intended to be found by ETs on the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecrafts. This iconic solid gold USB memory stick was not without a measure of bracing humour and lent wry relevance to the proceedings.

Jillian Mayer’s 400 Nudes consists of images of her own face pasted onto 400 nude selfies posted by women on the Internet, printed samples of which could be taken home by Bienniale voyeurs. This work presented an insistent and extended critique of a culture mired in online pornography and narcissistic exercises in Snapchat, Instagram, so forth. The flip side of this contribution was a work far more pornographic and frankly harrowing in its invocation of violence and man-made mass death. I refer to Paris-based Swiss artist Thomas Hirschhorn’s profoundly obscene and not for the squeamish Touching Reality, 2012, in which a female hand traces through and occasionally zooms in on a selection of photographs of desecrated mangled human bodies on a hand-held tablet. This work brought the tremendum up close and personal.

John Massey’s Black on White, 2014, marked this maverick artist’s welcome return to Montreal. He essayed, in a suite of six prints of digitally scanned collages, a work of striking cacophony, the underlying methodology of which marked a new watershed of creative skill. In this spontaneous deconstruction of language, with its knowing nods to Gutenberg, Italian futurism and Net-mindedness, Massey performed a wonderful seppuku on language and image alike.

Abbas Akhavan, Fatigues, detail, 2014, taxidermy animals (American red fox, screech owl, northern flicker, white-tailed deer, red-eyed vireo, North American porcupine, Nashville warbler, Blackburnian warbler) and education activity. Courtesy the artist, The Third Line, Dubai and Galeri Mana, Istanbul.

The four curtains that randomly moved around the room in which the Masseys were installed—frustratingly blocking the viewing of some of them at any given moment, so that the entire array could not be taken in simultaneously—was understood at first as being a collaboration between the two artists—but no. Noted British conceptual artist Ryan Gander’s love of pranks and enigmas, his irreverence, playfulness and conceptual intrigue were all on display in Tomorrow’s Achievements, 2014—his moving curtains a procedural cryptogram that incited patience and encouraged viewers to decipher and engage.

Nicolas Grenier’s work Promised Land Template, 2014, functioned as a sort of exhibition hall within the exhibition hall, its wooden structure the housing for his always-salient critique of socio-political realities. Grenier is an exceptional painter, and the trio of paintings that was exhibited in the makeshift room (Promised Land Template, Incoming Flux and Rip Current) were at once beautifully rendered artefacts and brilliant articulations of the void at the heart of institutionalized methodologies which ensure suppression, extant power structures, strategies of border control and the hegemony of the State. Like Gated Community, 2009, and so much of his earlier work, Promised Land Template proposes a deceptively low-key, but in fact highly charged and effective criticism of authoritarianism.

In Preuzmimo Bencic (Take back Bencic), an experimental documentary film by Vancouver-based video artist Althea Thauberger, the artist persuaded authorities in Rijeka, Croatia, to permit her and a cast of 67 children between the ages of six and thirteen to occupy an abandoned 19th-century factory. The children perform the roles (and write and improvise the script) of artists, workers and others in a lovely and lovingly enacted work of theatre as they revisit the factory’s old role as a communal workplace in postwar Yugoslavia at a historic moment when its future is still so uncertain. Amidst so much bleak critique, this film was a rare beacon of hope.

Back, left to right: John Massey, Auto, 2012–2014, digital prints, 162.4 x 162.4 x 5 cm; Now, 2012–2014; Grind, 2012–2014; Futurissimus, 2012–2014. Courtesy the artist. Front: Ryan Gander, Tomorrow’s Achievements, 2014, four motorized curtains and processor, 4.6 x 11 x 8 m. Courtesy the artist, gb agency, Paris, Lisson Gallery, London and TARO NASU, Tokyo.

Amanda Beech in her Final Machine, 2013, focusses on a series of lectures given in 1967/68 by the French Marxist philosopher Louis Althusser at the École normale supérieure. They drew intense interest from the student body, coming to a close on the eve of the riots in May 1968. Beech’s three-channel video installation assumes the scaffolding of Althusser’s lectures as a sensible methodological framework, imbricating his political philosophy with transcripts of a CIA recruitment talk and other rogue source material. The narration, by a single garrulous American, is punctuated by gunshots that lend telling urgency to the pronouncements. Beech has methodically and deftly honed an analysis anchored in a nexus where sociology, politics and meta-fiction meet, merge and morph, empowering scepticism and fostering a post-political reality based upon the lessons and usefulness of philosophy as a means of knowing surrounding reality. “Final Machine” is knowing, taxing, edgy—and hugely compelling.

Finally, and to come full circle (at least geographically), Kevin Schmidt’s A Sign in the Northwest Passage, 2010−present, shown alongside Richardson’s Orion Tide at the Quartier de l’innovation, gave new meaning to the word ominous with his large free-standing cedar hoarding and its hand-routered, dire pronouncements from the Book of Revelation. Schmidt drove the sign from Vancouver to Tuktoyaktuk, Northwest Territories, where he installed it on the drifting ice of the Northwest Passage. This floating prophecy of the End Times was a haunting indictment of those responsible for climate change and a fair warning to us all of its consequences.

Other artists whose work in the Biennale deserves special mention include Nicolas Baier, Andrea Bowers, Skawennati, Lisa Steele & Kim Tomczak, David Tomas and the ubiquitous American senior artist and word-meister Lawrence Weiner.

As is apparent from the foregoing, the vast preponderance of work exhibited was installation and video-based. If I am remembering correctly, of the 50-some participating artists, over half employed video or film in some form. The total combined running time was simply unassimilable even over several visits. Excess may be a virtue, but here it obviated both message and potential. So, did the exhibition speak to painting? Sadly, no it did not. But it could have. After all, as was apparent in the work of Grenier and a bare handful of others, radiant critique flourishes in that medium, too, and thus it is unfortunate that the curators chose to look away from the promise of painting in addressing the uncertain future Derrida so eloquently spoke of. ❚

The Montreal Biennale: “L’avenir (looking forward)” was exhibited at the Musee d’art contemporain and various other venues, October 22, 2014 to January 4, 2015.

James D Campbell is a writer and curator in Montreal who is a frequent contributor to Border Crossings.