The Matter of Art

In 2011 Winnipeg artist Toby Gillies received a Manitoba Arts Council Grant to work as an artist-in-residence with an elderly group of men and women who were in 24-hour care at the Misericordia Health Centre. The 8 to 12 people he worked with suffered from various physical and cognitive disabilities. He would meet with them two or three times a week. The art that has come out of the workshops in which he and the staff at the Misericordia have been engaged was on exhibition in the Ace Art Project Room for three weeks in November. The show, called “Still Life,” refers to the slowness with which the artists work, and it also underlines how lively they remain. The participants range in age from 65 to 105 years.

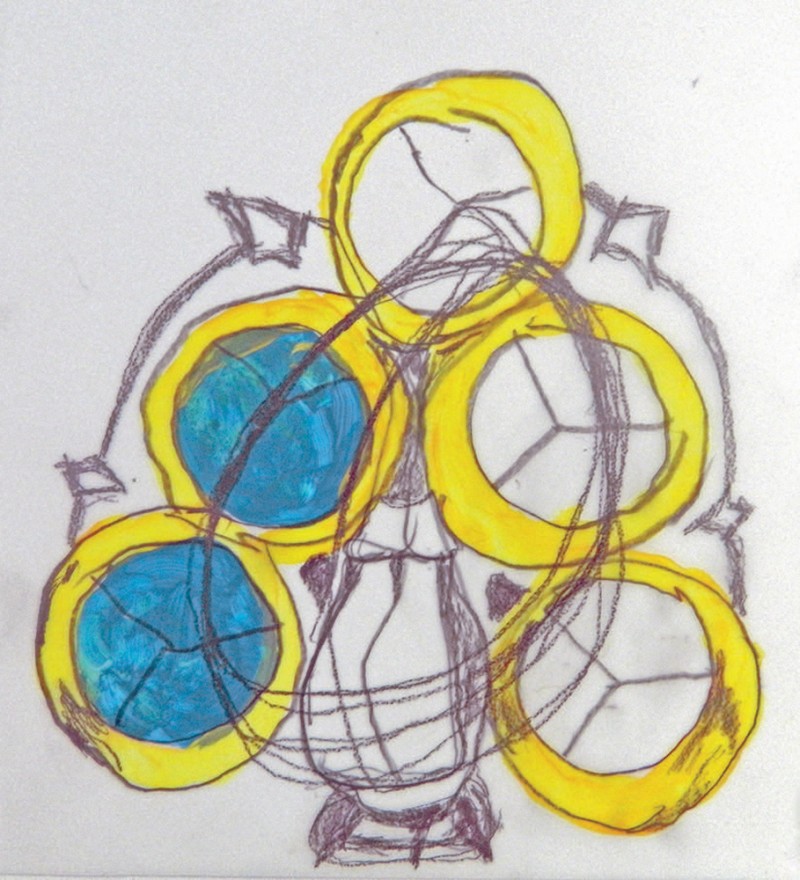

Frank, Time Machine, 2013, 5 x 5 inches.

“Still Life” is the kind of exhibition that makes you realize why art matters. Every one of the artists Gillies has chosen has been made better through the making of their art, just as we are in looking at it. The variety is remarkable: untutored, unselfconscious and utterly convincing. (The exhibition includes a pair of videos: in one the artists talk about their work and in the other, shot by Natalie Baird, we see their expressive hands making the work).

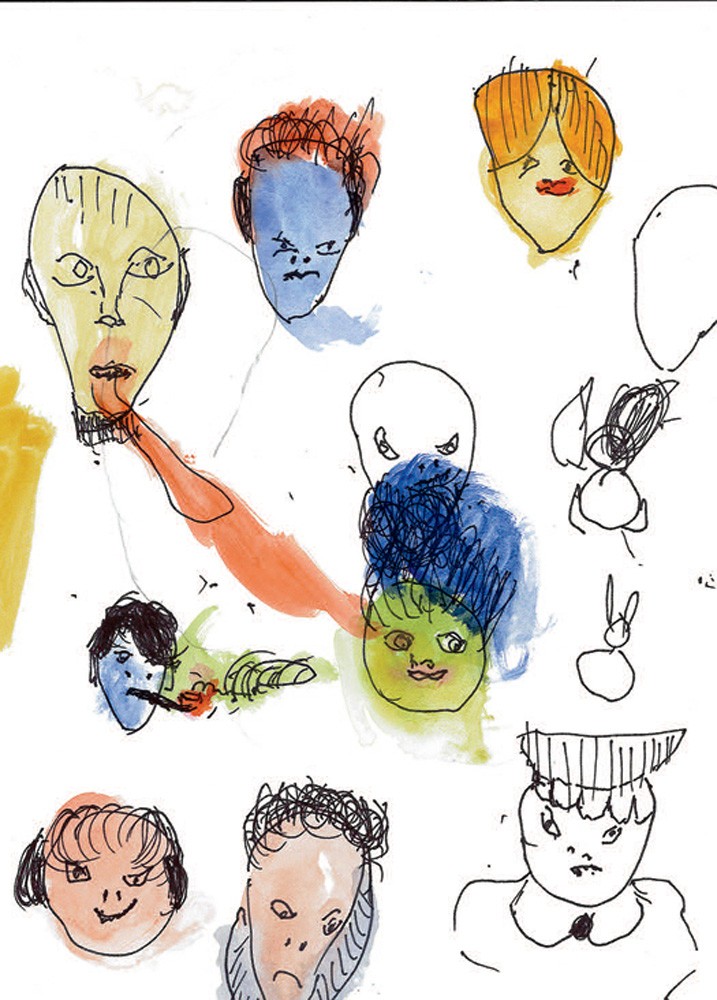

All the drawings seem to have an accompanying story. A series of expressive heads by Ina was the product of her attempt to paint a portrait of her dead daughter; each of the figures she comes up with morphs into a unique head study. Mary, who spent years in a German concentration camp, paints a beautiful series of abstracted coloured lines coming off two sides of a peachy stem; Angela who grew up on a farm, draws a gorgeous multicoloured small bird; and a cowboy and his horse meet another horse in a delicate unsigned drawing made by a former heart surgeon.

Gillies brings into the workshops art supplies and a modest library of books on art, natural history and botanical drawings. You can see their generating influence. To help Trevor, a stroke victim who spent much of his time crying, Gillies would turn the pages of a book on Renoir. After a while he stopped crying and began to paint; the shapes were Trevor’s, the palette was Renoir’s. Frank, who was suffering from severe depression, traced a watch ad and by repeating the image, constructed a collage of a time machine. It is a wonderful rendition

Ina, Drawing started as a portrait of my daughter, 2014, 10 x 12 inches.

Al, Fast Moves, 2012, 5 x 11 inches.

One of the most engaging drawings in the exhibition is called Fast Moves. It is one of the first pieces made by Al when he was in interim care. Through combining a page from an issue of Sports Illustrated and a piece of acetate and tracing over a pair of Picasso sculptures, Al comes up with a painting that works on our imaginations in the manner described by its title. In “Still Life,” this image moves fast. ❚

To order this issue, click here.