The Malcolmson Collection

A quiet but palpable sense of discovery hovers over The Malcolmson Collection. In the passage between the foyer and the east gallery of Presentation House, we come across a veiled image and, lifting the small piece of grey fabric, we see the oldest work in the show. Titled York Minster from Lop Lane, it is an 1845 salted paper print by William Henry Fox Talbot. Age is a significant factor here: Fox Talbot was, of course, one of the inventors of photography, and the architectural subject of this early street scene is now fading into a ghostly haze of tone and form. Dissolving into the irrecoverable past.

The Fox Talbot print is one of 110 historic and contemporary photographs chosen for exhibition from the esteemed collection of Ann and Harry Malcolmson of Toronto. Every old print in the show is vintage and many are rare, the work of both acclaimed and anonymous photographers from Britain, Europe, the United States and Canada. In addition to salted paper prints, there are albumen prints, calotypes, cyanotypes, photogravures, wax paper negatives and gelatin silver prints on view, along with a small selection of books, albums and portfolios. Chromogenic and inkjet prints by contemporary photo artists such as Thomas Ruff, Ian Wallace, Evan Lee, Scott McFarland and Jeffrey Farmer introduce interesting inflections of colour and attitude into the otherwise monotone assembly, while Mark Lewis’s DVD Gladwell’s Picture Window insinuates flashes of movement.

Man Ray, Untitled [Solarized Portrait], c. 1930, gelatin silver print.

Shot on 16 mm film on a sunny street corner in London, Lewis’s work is an almost magical congregation of second-hand images: passing cars, pedestrians and bicyclists are seen as reflections—and sometimes double reflections—in the curved glass window of a commercial art gallery. The paintings on display behind the window seem to be partially dissolving in the shimmery layers of rebounding light and reflected motion. Complicating the optics, the camera swings up, down and sideways.

Much as Lewis’s work seems to allude to the earlier photographs of Lee Friedlander (something artist Adam Harrison has pointed out), it is also possible to find a reference here to the history of landscape painting through the 18th-century device known as the Claude glass. Although Lewis has created a streetscape, he stimulates our thinking about the way cultivated personages were once advised to view a landscape, framing and composing a scene using the convex surface of a hand-held mirror. Lewis’s art summons up not only the history of picture making but also its present, with evocations of the ways in which our perceptions are technologically mediated. So much of contemporary life is viewed second hand through glass—not as reflections, but as photo-digital images seen through computer screens, TV screens, video screens and the tiny screens of hand-held electronic devices. A Blackberry is now comparable to Claude’s little mirror—as if direct visual experience were incomprehensible, as if every image and sensation must be reduced, framed and processed through some other medium or device before they make sense to us.

While many photographic methods, styles and subjects are represented in the exhibition, Presentation House Gallery curator Helga Pakasaar has identified a few prevailing themes and ideas. The exhibition, she writes in her curatorial essay, demonstrates that “photography is an act of drawing with light.” A literal case in point is Roger Parry’s 1931 Untitled (Photogram), an abstraction of squiggly and spiralling lines of light drawn down the dark surface of the print. Pakasaar observes that the visual effects particular to the physical properties of photography contribute to the “poetic and elegaic mood” present in the show.

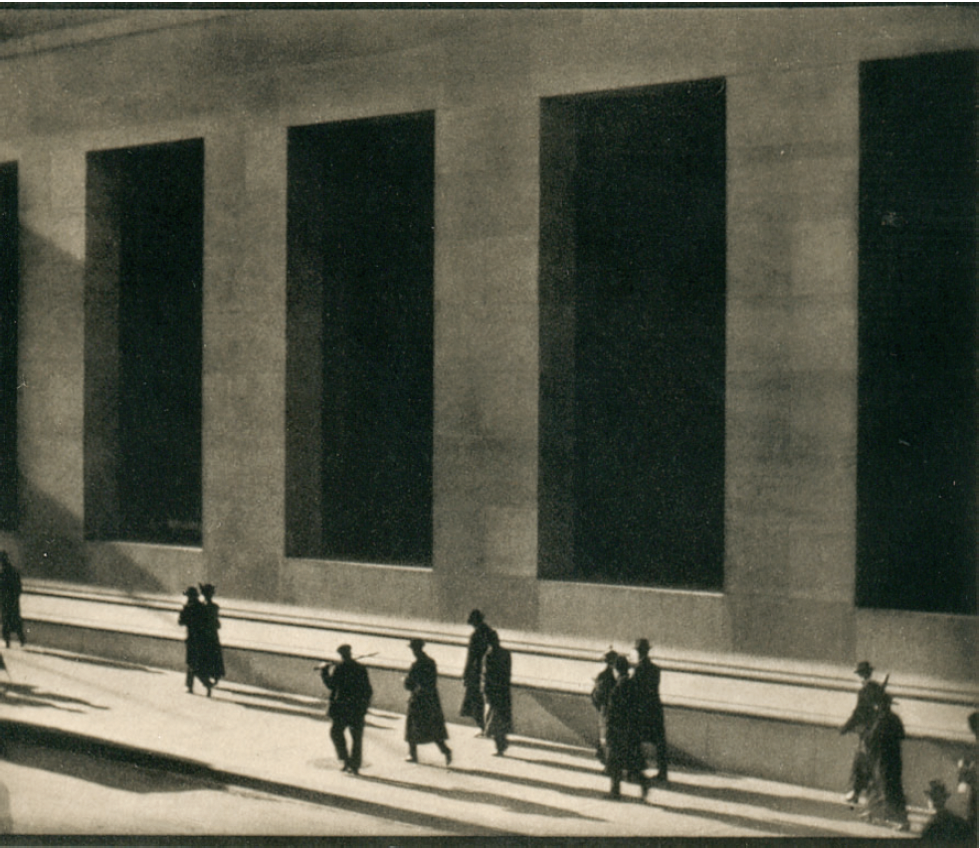

Paul Strand, Wall Street, 1915, photogravure.

In establishing their photographic collection, the Malcolmsons were drawn initially to experimental images from the early 20th century. (There are a number of Man Ray works on view, mostly studies of women altered through various technical means, including solarized photos, “Rayographs” and odd, fun-house-mirror-style distortions.) From this early Modernist start, the Malcolmsons expanded their collecting in either direction: backward into the 19th century and forward into the 21st. Many of the pioneers of photography and their heirs are represented, including David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, Adolphe Braun, Charles Marville, Gustave Le Gray, Charles Nègre, Julia Margaret Cameron, Eugène Atget, and Peter Henry Emerson.

Some of the giants of Modernist photography are also here, such as Edward Weston, Walker Evans, Manuel Alvarez Bravo, André Kertész, Joseph Sudek, Bill Brandt and Margaret Bourke-White. The images on view range from the familiar—Alfred Stieglitz’s 1907 Steerage and Paul Strand’s 1916 Blind Woman, for instance—to the little known. Among the latter, Hollywood Premiere, a 1956 gelatin silver print by Robert Frank, depicts a bored young woman in a movie theatre box office. (This work, too, plays with reflections, refractions and figures partially seen through curving glass.) A number of quite remarkable anonymous photographs also have been vetted into the collection, including an 1860s interior shot of a Japanese tea room.

Also anonymous is a tiny 1920s glass positive of a light bulb. The work, which is installed in, rather than on, the wall and backlit beside the projection of Gladwell’s Picture Window, is exquisite in its singular focus, its clarity and the scientific and allegorical possibilities of its subject. The image of the clear glass bulb, the glass on which it is printed and the window-like installation are all reiterative of the window element in Lewis’s DVD.

Hans Bellmer, La Poupée, 1937, hand-coloured, gelatin silver print.

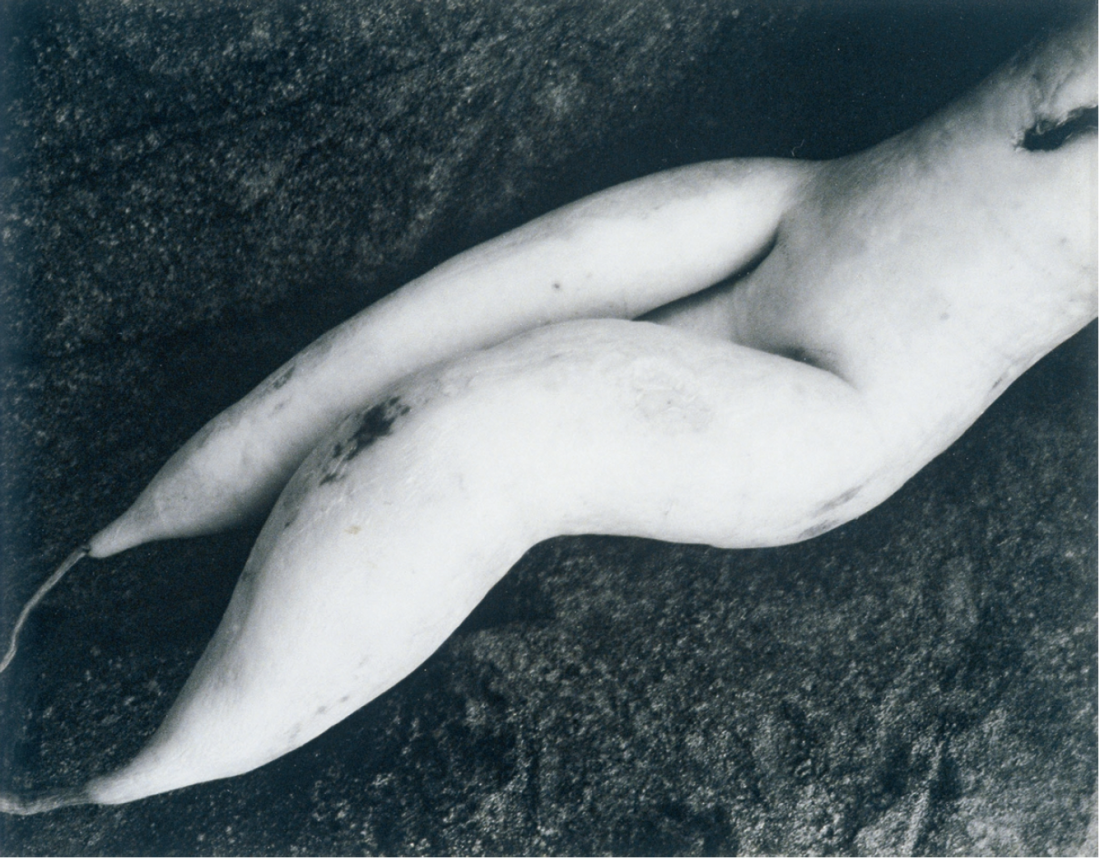

In installing the collection, Pakasaar has established many such thematic and imagistic resonances, so that chronologically disparate portraits are mounted together, as are images of trees, street scenes, archeaological sites, industrial forms, crowds at circuses, parades and political rallies, and so on. In one grouping of photos, for instance, Edward Weston’s anthropomorphic White Radish, which closely resembles the lower half of a female nude, is reiterated in a number of works hung nearby. These include Nude on Floor, Paris, an anonymous work from the 1950s, Frantisek Drtikol’s 1932 Cut-out Figures, Prague, Jaroslav Fabinger’s Blonde, c.1930, and Hans Bellmer’s 1937 La Poupée. It’s difficult to look at the early modern nudes in the show without noticing how many of them are made headless through some compositional device or other. And it’s impossible to look at Bellmer’s doll, with its conjoined-twins combination of female legs, hips, abdomens and genitalia, without perhaps thinking “misogyny.” All representative, I suppose, of a certain age and attitude in the male-dominated history of photography.

A rather lovely antidote is provided by Aenne Biermann’s Untitled (Nude study of Anneliese Schiesser), c.1931. Here, it seems as if the bare-breasted portrait subject is that—a subject, not an object. And there is unexpected delight in the way the delicate fringes of her black eyelashes are echoed in the dark fringe of her underarm hair. Again, there’s that sense of quiet discovery.

Also evident among the images here are intimations of mortality. Bare branches, broken windows, empty streets, all singing the elegaic note that Pakasaar has observed. And there’s a more direct address of death, too, through images of Arab funerary inscriptions, a burial mound in Algeria, an execution ground in China and a withered, partially shrouded corpse in Mexico, its lips drawn back in a ghastly grimace.

Edward Weston, White Radish, 1931, gelatin silver print.

The fugitive quality of the photograph—the ephemeral capture of light reflected off a face, a pond, a pane of glass, the peaceful or violent passing away of the subject followed by the brief life and eventual fading of the photograph, too—all support Roland Barthes’s remarks about how closely the photograph is allied with death. In Camera Lucida, Barthes asserts that photographers are “agents of death,” even while supposing themselves to be committed to the act of preserving fleeting aspects of existence. In this exhibition, death is both text and subtext.

Some cultural theorists believe that a sense of mortality also informs the impulse to collect, to gather together large numbers of like objects, to put the stamp of taste and order and ownership upon them, to register them as precious and to preserve them. But that stamp is fleeting, too, ephemeral, fugitive and, like the Fox Talbot photo, hanging behind its protective curtain, destined to fade gradually away. Destined to join the other ghosts that haunt this time and place. ❚

The Malcolmson Collection was exhibited at Presentation House Gallery in North Vancouver from October 1 to December 20, 2009.

Robin Laurence is a writer, curator and a Contributing Editor to Border Crossings from Vancouver.