The Incredible Lightness of Bee-ing: An Interview with Aganetha Dyck

It’s Aganetha Dyck’s confirmed sense that we inhabit, collectively, one interconnected world, that any situation, any changes, all assaults, are felt globally. But the large world is difficult to comprehend or know well. A better plan, a more manageable approach, is to hive off some segment, some microcosm to represent this large world, to have a part stand in for the whole and select, for close scrutiny, one small subject. For Aganetha Dyck this subject is Apis mellifera, the honey bee. Metonymy isn’t a tactic she’s newly applying. In early work she presented felted sweaters—compact, woolly, person-shaped carapaces cavorting in unnerving and amusing disarray wherever she installed them; in another body of work her elaborated, decorative, bound and embalmed cigarettes implied, always, the absent smoker; more recently, the garments and accessories of her wedding party installation were redolent with beeswax and absence. In each case the objects referred to, and represented, other subjects, made us look elsewhere, further, and question what it was we were seeing. And in each case, whether we had answers or not, the work served to amplify the present and ask, in what way do we gather intelligence, how do we reconnoiter the world around us? With the bees as agent, it seems Aganetha Dyck has found the ideal sleuths.

It’s been a long-standing conceit and misconception that women are more material than men, more a part of nature, more intuitive, less rational, but Joseph Beuys had no difficulty identifying with nature. On the contrary, he sought out a physical association with animals as a way of gathering from them what was intuitive, what he believed to be a superior form of intelligence. For Aganetha Dyck, work is willful and conscious and full of intent; instinct is really another way of defining applied intelligence. People would tell her she worked intuitively and she believed that such a person was not a thinking person. Then she came to realize that she thought about what she was doing a lot and that it was very complex. However, the intentionality of her work doesn’t mean she fails to acknowledge the role the bees play; she identifies them as collaborators. Deferentially, she attributes a good portion of the finished work to them but recognizes, as an artist, that it’s difficult to yield credit. They’re integral to the work—there’s no question there—but the intention, the first gesture, is hers; primum mobile, she sets it in motion.

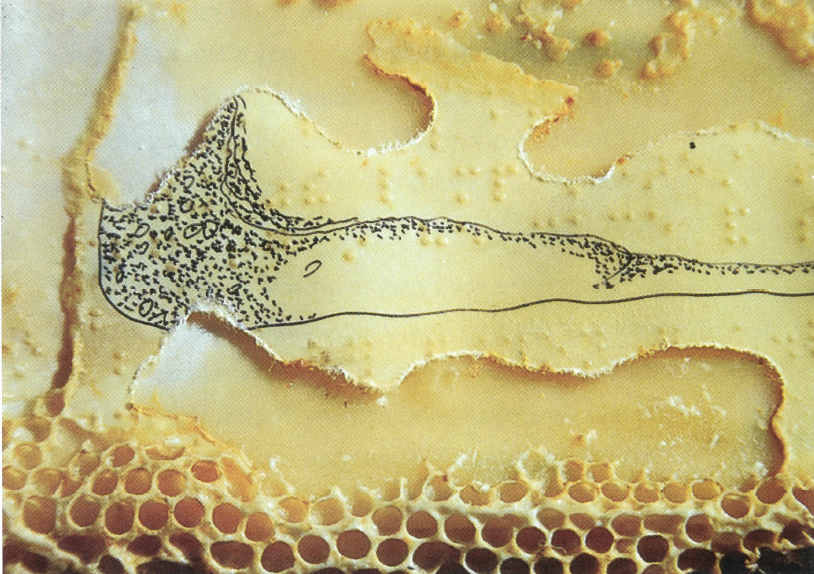

Bees working on line 1 of the Braille/poem, 1999. Photograph: William Eakin. All photographs courtesy the artist.

Poet Emily Dickinson, seeking to conjure a prairie, identified the necessary components: “To make a prairie it takes a clover and one bee, / One clover, and a bee, / And revery.” For William Butler Yeats, seeking peace, he’d need to retreat to Innisfree where: “Nine bean-rows will I have there, a hive for the honey-bee, / And live alone in the bee-loud glade.” Both recognized and named bees as collaborators in achieving peace and prairie. Aganetha Dyck, in wishing not to undervalue their creature intelligence or industry, could call her work a project of autorenschaft, or multiple authorship, and be comfortable with that designation.

In The Creation of Feminist Consciousness (Oxford University Press), Gerda Lerner cites Emily Dickinson as someone whose art brought her into being. Speaking for Dickinson, she wrote, “My weakness entitles my speech to heightened significance, not only because I am ‘God’s trumpet’ … but because I am common, like household chores, like the dailyness of women’s lives, like the humble bees and birds and meadow flowers.”

When Aganetha Dyck moved with her husband and small children to the town of Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, she was expected to participate through volunteer work in the community. Assessing what was possible, she discovered a comfort with, a felt affinity for, the town’s Art Centre. Through the domestic task of providing meals for visiting curators and artists, she began an association which led to meeting artist George Glenn, who was teaching art and, incidentally, looking for someone with whom to share studio space and rent. The crocheted pieces she was making on her own were sufficient to earn his invitation. He and Margaret Van Walsem, who also shared the large space, became Aganetha Dyck’s teachers and mentors. They gave her permission as an artmaker, she said, and while it’s true that encouragement helps and is often the necessary impetus, Aganetha Dyck gave herself permission. She noted other artists and their technical proficiency and their schooled knowledge; authority and its imprimatur are tyrannies under which women have always operated. But using homely skills and the daily materials at hand, acquiring technique and establishing process for herself, Aganetha Dyck pulled the domestic rug out from under that argument, made art and was an artist. In housework there are no hierarchies; it’s all work to be done, ordinary work which requires attention to close, small matters. In art too, Aganetha Dyck is interested in “the power of the small.” Appropriate in this age of contagion and fragility, she’s referring to bacteria and viruses, and she draws in her attention to focus on a single drop of honey. “In this,” she tells us, “is the history of all beekind.”

Poem/Illustration, detail.

She explains a recent project titled “Working in the Dark” as dealing with “translation, transcription, transformation and transmutation.” Based on bees’ transferring experience and information non-verbally, the work questions the possibility of some mutual bee-person language—a means of communication that could find common ground. Since scientists believe bees are not sighted in ways familiar to us, they are, in effect, working “in the dark,” reading the world through other senses. Like Braille, it’s a form of script. Aganetha Dyck finds both unreadable. In a creative attempt to decode these communications, she invited Di Brandt to write a poem for her. This was transcribed in Braille on 54 paper tablets, one for each line, and placed in the hives so the bees could reinscribe the tactile text in their own language. The poet began, “& then everything goes bee / sun exploding into green / the mad sky dive / thru shards of diamond light/ earth veering left then right / then left…”

Every day, like a mantra or prayer, Aganetha Dyck draws bees or bee parts, small drawings, meticulous and tender. She calls them tiles, often covers them with melted wax, or waxes the paper and inscribes the smooth surfaces. The bee, under a glaze of caramel, under a tint and patina of age, in warm ochre like Joseph Beuys’s familiar drawings done with ferric chloride, cartoons of joy, of sheer pleasure, of scientific, anatomic curiosity from an earlier time, over and over—these drawings.

Bees work in multiples—repeating their perfect waxy forms, committed to geometric symmetry, little hexagonal chambers. Over and over—the same artful production, early intuitive anticipators of Walter Benjamin’s “art in an age of mechanical reproduction.” Repetition brings a certain succour and tranquility, and there’s an almost sublime achievement in directing attention to one topic, with care. Aganetha Dyck continues to interrogate her world—immediate and more distant. She sees the pieces and parts as an entity. Around her, working with her, are the bees pointedly stitching it whole.

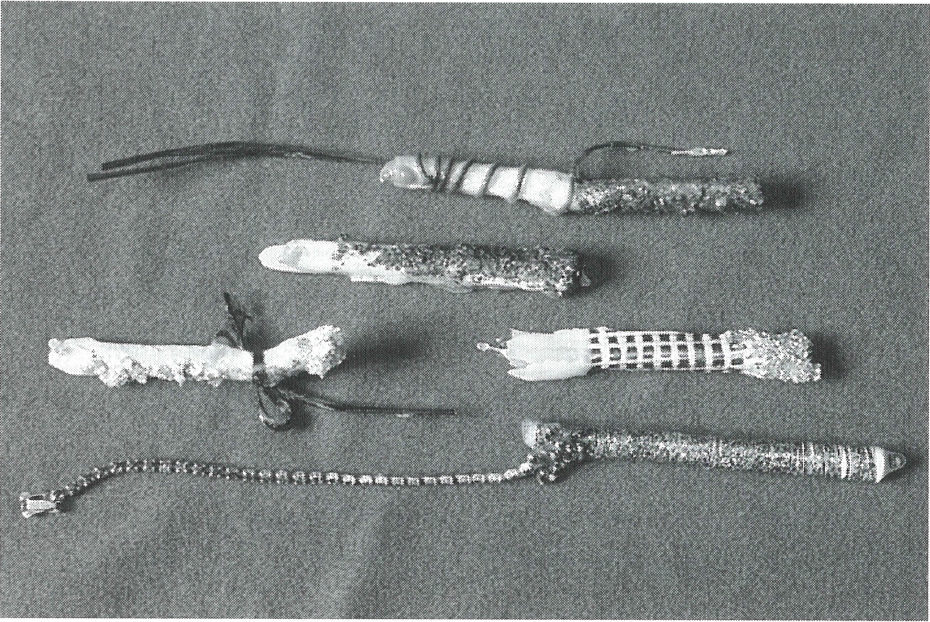

Altered Cigarettes, 1988. Photograph: William Eakin.

This interview was conducted by Robert Enright in Aganetha Dyck’s Winnipeg studio in March 2000.

BORDER CROSSINGS: I want to talk about your birthplace and what it was like growing up in Marquette.

AGANETHA DYCK: My father was a welder and a farmer. If your father’s a welder you have lots of toys. My grandparents lived half a mile from our house, through the woods and along the river. All the fairy tales like Red Riding Hood and all those scary things were in there. It was great fun to tear through the woods to go to grandma’s house. It was really beautiful. I had a very good childhood. But we were very poor. We lived in a two-room log house. Dad had a fishing line in the river because we were survivors. We had an old airplane in the yard that we played in all the time. It was a bomber, but the funny part was, we didn’t know what it was. We didn’t play at dropping bombs on anyone, or on the cows or anything. We didn’t know about those things. We came from families who didn’t do that. Dad bought the airplane so he could strip it for parts, like wash lines. He’d buy machinery and it wouldn’t suit his method of farming, so he’d improve on it.

Did you help your father with chores?

I was the worst farm kid—I was scared of cows and chickens. My mom said I had to learn how to eviscerate a chicken but I wanted the rubber gloves like they had in the city. I would not do it. I also milked the cows from a distance, as far away as my hands would reach. I couldn’t wait to get out of there after I was a teenager.

How did you arrange that?

By going to junior high and high school. I stayed with grandma, who was then in the city. I liked the farm but I didn’t like the barn and anything that went with it.

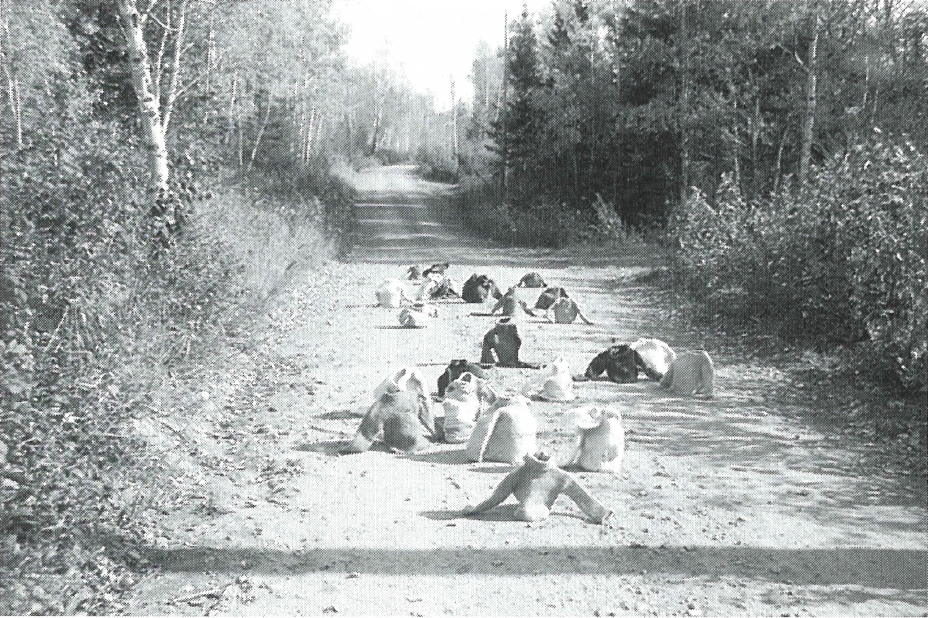

Shrunken Clothing on a Road, 1976-1981. Photograph: Peter Dyck.

Did you have a religious upbringing?

With a twist, I think. We were Mennonites who went to church every Sunday and we went to German school to learn the language, but every Saturday we followed the hockey teams around Manitoba. We loved hockey as a family. And then we also went to all the movies at Portage la Prairie. We’d go to a movie and then the hockey game or vice versa. And my father believed in dancing. He even bought a schoolhouse for the young people of the church so they could dance. We didn’t have cars that we could head out to Winnipeg in and maybe he didn’t want us to. So we had record players and people with instruments and we danced.

Did you have any inkling as a child that you were interested in art?

I don’t think so, except that I was a big Elvis fan as a young teenager. We had to clean the house every Friday and I would redecorate the log cabin all the time. There were things that weren’t done on the farm, like wine-coloured drapes. In those days they were all flowers. So I dragged my mom to Eaton’s and we got this wine-coloured material. We loved them. How much interior decorating can you do in a log cabin? I wanted to be modern. I’d also move furniture, probably to improper places.

You were a benevolently mischievous child, then?

I was a mischievous child, yes. But the mischief was usually in play.

The Large Cupboard, 1993, studio installation. Photograph: Ernest Meyer.

What was high school like for you?

I failed Math so I had to take Business Education, which I passed, and then went on to become a business machine operator a year after high school. I was already 19 years old and I didn’t really have a guy I was going to end up with for the rest of my life. So this job was okay but people looked at you and wondered why you weren’t attached. Education wasn’t important.

Obviously you met the guy, an event which pretty well changed your life.

That changed my life. We were 20 years old, got married and had a baby. As luck would have it, our children were the type who didn’t like TV—they watched only one 15-minute program a day as they grew up. Nothing worked for me, I had to play with the kids. I was pretty sad.

You first started making art in Prince Albert, didn’t you?

Yeah, I think I was 37 or 38 years old. My husband was an Eaton’s store manager and, you’ll never believe it, I was a size seven and had a bouffant hairdo. Every week I’d go to get my hair done. It was so tiring. Then it was the feminist movement and people were wearing Why Not buttons. When we moved to Prince Albert we were courted by everybody, the Kiwanis and Kinsmen, and I was expected to be a corporate wife.

Would you have been fancy people in Prince Albert, coming from Winnipeg?

I don’t know if we felt that, but it was Peter’s position in the community that was important. I was just this appendage over here, but I couldn’t join anything because I didn’t fit in. I didn’t have white gloves. I don’t fit into a lot of places. I thought, they’re expecting me to do volunteer work, and I had three little kids, so I went around town, it’s not a big town, and I saw the Art Centre and I just fell in love with it. I thought, I can volunteer here, so I did. George Glenn’s studio was in the basement across the street in the Harold Building. He was my first mentor. He had his MFA from Chicago. My job as a volunteer was to feed the people or take them around in the community. Carol Philips came up and people from Regina and Saskatoon to see the art in PA., and to meet George and people like that. When they came, they came to our house for lunch or for dinner. When George came to my house, I was just crocheting to keep busy. I didn’t know anything about art so I was reading as much as I could, and I was crocheting a mother and child but it was a pig. It was pretty bad, but it was sort of in the round and it was out of copper wire from the inside of a car engine or something. I had other things that I crocheted, I don’t know, walls and things. George really liked what I was doing. I guess he was desperately looking for someone to share his studio because he couldn’t afford the whole thing. He asked if I wanted to share space. So thats what I did. I went down there but I didn’t know what to do so I started shrinking clothes; it makes me laugh but I did do that.

The Pocketbooks for the Queen Bee, 1991, installation, Winnipeg Art Gallery. Photograph: Ernest Meyer.

There’s two versions of the story: that you shrunk the clothes or that you discovered the shrinking process because someone accidentally ended up shrinking something.

I was apprentice to a weaver, Margaret Van Walsem, and it didn’t fit my personality at all. I’m trying to think of how that worked. It wasn’t me, it was an elderly lady in her 90s who was a sheep farmer, and it was from her that we purchased the sheep fleece for weaving. Under Margaret’s very strict rules, it was expected that we get this ugly fleece, pull it apart to get out all the dirt, then wash it, dye it and spin it. This lady had a beautiful marino fleece and she asked, ‘Do you want me to wash it for you?’ and I thought, oh good, she’s going to do this. But she threw it in the washing machine instead of her clothes. You know, on the farm you had white bundles and coloured bundles, and the fleece was the first one she threw in. She phoned me and said she was very sorry but the fleece was stuck around her agitator and she couldn’t get it out, so I jumped in the car, took my knife and scissors, and cut it out. It was really gorgeous; it was shaped like the agitator. And it was just as hard as a rock. I was very excited.

I guess Margaret wasn’t.

When Margaret and George came in I said, look, and they looked, Margaret said, that’s felt, and I said, I want to do this, this is great. So she asked me, why don’t you prove that you can make something out of this, not just throw it in the machine? She also explained how they shrank the Hudson Bay blankets, and that’s why they’re so warm. At that time I was taking pottery, so she said, ‘Why don’t you weave a giant cup?’ I thought, God, this is too hard, so I took a jersey blouse or something, wrapped it with wool and made it look like a cup. I bought a machine and threw the Jersey in. I took it out and it was a cup. So I said to Margaret, ‘This is a cup, I can do it.’ Then I thought, I don’t really want to make cups because there are already a lot of them around, so I decided to try something else. I figured I’d find something out there in the public. I thought, what about clothes? Nobody wants wool clothing because it’s super wash time. I went to the Salvation Army and they were throwing out tons of woollen clothes. Some were moth-eaten. I took them all and just started washing. I didn’t tell anyone. When they were small enough I’d sit them in the basement studio—I was in the back—and when I had a number of them I made George a cover for his teapot. I really wanted him to see it but I was scared because he had his MFA and I didn’t know what I was doing. He finally asked me and I said, ‘Well, I’m shrinking clothes.’ So he came, and while I didn’t see it at the time, it was this amazing sight. He said, ‘If you were in New York, you’d just take off.’ So Margaret and he both said, ‘Go with our blessing, do anything you want.’ And I did.

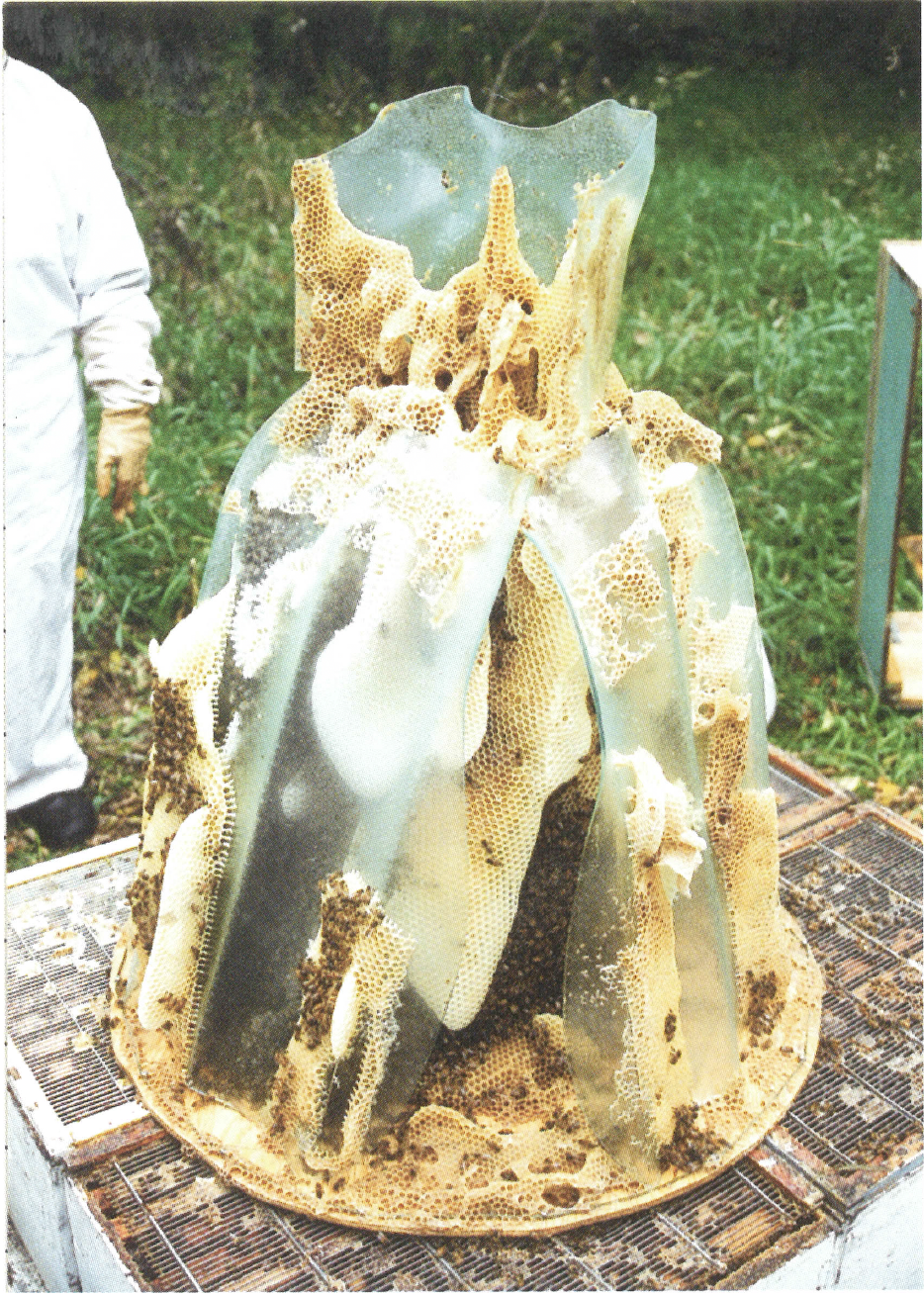

The Glass Dress/Skirt, 1998, detail. Photograph: Peter Dyck.

That’s when you began to arrange the small pieces of clothing so that they looked like clusters of people. Did you establish scenarios for them? Did you imagine stories?

They were just people to me. Then someone would come along and say, ‘Do you want to shrink my sweater?’ because it was old or something, and then there would be something of her in this sweater, because our bodies make a shape. I started to see that quality in those clothes but Margaret kept talking to me about having a technique. I noticed that the painters in the area all had techniques. They knew what they were doing. I didn’t know what I was doing, so I thought, okay, I guess I have to go back to felt, which I did. Then I received a Canada Council grant—for me that was a huge amount of money—and I purchased refrigerator-sized boxes of beautiful clean fleece. I experimented for two years and felted hundreds of things.

So you taught yourself how to use the material you were working with?

And make the shapes I wanted. I just knew how to do that. I’d make trees, I’d make anything I wanted. It was a good time to go through, although maybe it would have been better had I gone to school or something. But that was the way I worked.

Was the approval of George and Margaret a big lift for you in the sense that it gave you permission to call yourself an artist, even though at the time you seemed to have no idea what you were doing?

What I found so generous was that they both really accepted me. We had a little coffee room and every time there was coffee they’d call me. I was hesitant because one day I had walked in and George said, ‘If this painting doesn’t work, I’m cutting my ear off.’ Margaret laughed and laughed and I said, what’s funny about that? She said, ‘Well, you know, van Gogh.’ I didn’t know who that was. That’s when I really knew I had to do a lot of reading. After that we always had these discussions. They were like a school for me. I studied drawing with George, and he taught me a little bit about art criticism. I took every course he gave at the community college. I learned how to draw, I learned a little bit about art history and I learned how to see. Then because of Peter’s job I was elected to City Council as an arts representative. I was the Organization of Saskatchewan Arts Councils’ rep for our region. It wasn’t me, it was who I was married to. But I was learning a lot. I met all the curators and every time they came to the studio they’d want to put my work into a little exhibition somewhere. Art took me over. The kids went to school and I’d go to the studio; I’d come home at lunch and then go back to the studio. It just changed my life.

Bees working on Glass Dress, 1994. Photograph: Peter Dyck.

How long were you in Prince Albert?

Four years. I studied with George for a year. But they gave me the permission. Every once in a while I’d go on a tangent that didn’t make any sense, and if I invited George to my space, he’d say, ‘Well, that doesn’t work, does it?’ He wouldn’t ask me why or anything, he’d just say, that doesn’t work.

And was he right?

Oh absolutely. I even knew it deep down. When I got to Winnipeg George said, ‘What are you going to do?’ and I said, I’m going to get a studio. I had one within a week. I phoned Don Reichert; I didn’t know him from a hole in the head, but I knew I had to get into this art community as fast as I could. I asked him to the studio, because I needed support for a Canada Council grant, and he came.

Was it moving into this space where you found the buttons?

Yes, it was up on the fifth floor. I was sharing studio space with three other artists. And Wanda Koop was next door. I don’t know if it was curiosity, or whether it was a show I’d had at the Oseredok Gallery, but she stopped me on the street one day and we talked. She wanted to see what I was doing and she said, ‘You’ve got to get out of here, you should be out by yourself somewhere.’ She felt I was too cramped. I said, ‘Where will I go?’ and she said, ‘I don’t know but get your own space.’ She and Suzanne Gauthier took a lot of time with me; it was sort of like George and Margaret all over again. They were very supportive. And every time Wanda had visits from curators she would send them to my space. I met Jack Butler when I had a show at Plug In with all the shrunken clothes. I met Max Dean at that time. Max was putting a garage up at the WAG. I was just frantic to meet these people. I wanted to know what was going on in the community and I wanted to be in it. I was going down the stairs one day from the fifth floor and I met this very tall, handsome man. I’d seen him before. He’d always go high up and I’d hear him puttering up there. One day he said, ‘Are you an artist?’ and I said yes. He said, ‘Do you want space?’ This was right after I had talked to Wanda. So I went upstairs and it was all buttons up on the fifth floor. I said, ‘What is this stuff?’ and he said, ‘Well, I’m a button dyer and manufacturer’ And it was like my paint had arrived. I thought, how can I get these buttons from this guy? I don’t have any money. Then he said, ‘I’ll rent you the whole floor for $150, if you buy the buttons from me for $500.’ I didn’t have $500 but I said okay. We had just moved not long ago and we’re not poor, but we never had enough money so that you could just grab $500. But I said, ‘Okay, when do you want the money?’ Because I had looked at these buttons and I thought I just had to have them. They were so amazing, leather, glass, everything. I walked down the stairs with him and I went to the Royal Bank. When I think of it, it was really embarrassing because I didn’t even change. I walked to the corner and I said, ‘I need to see the manager right now.’ I guess they let me in, thinking, my God, we’ve got to get her out of here. But they didn’t. They said okay and there was a glass room where I went and sat down and the manager said, ‘What can I do for you?’ I said, I need $500. They gave it to me without Peters signature. To this day I don’t know why. It must have to do with how passionate you are about something.

The Glass Dress, 1990-1998 Photograph: Peter Dyck.

Did you tell the manager that you wanted to buy buttons with it?

I told her that I wanted to buy this whole floor of buttons and that I was an artist. I took all the stuff I had. She put it up on her desk and said, ‘When do you need the money?’ So the next day I bought them. Then I found out he should have paid me $500 because the space was such a mess. He would have had to pay someone a lot of money to haul everything out of there.

Did you know that buttons were going to be what you would use for the next number of years as an artist?

I did but I didn’t. I was felting and I had to move all that material. I moved upstairs right away and got the Mennonite Theatre to rent half the space, because of the $150 rent plus the $500 that I now owed. I just opened boxes and I traded for a whole year. All I did was trade buttons or Christmas baking for art supplies. I can’t remember the names of all the people who actually traded—lots of artists. It seemed like there were billions of buttons. People could choose a box of buttons and give me whatever they wanted. It would be something I could use, paint or glue, or coffee. Then I didn’t know what to do with them. Everybody had ideas: sew them all over my clothes, glue them all over the wall. But early on in my career, George had said, don’t try to be who you aren’t. You can only make art from who you are and where you come from and what you think. So I thought, okay, George, here I go. First I did the laundry, now I’m going to do the canning. So I did and I loved it. Wanda really encouraged me. I made about 20 jars and had a visit from the Manitoba Arts Council for a Major Arts Grant at that time. I remember there were three jurors—one was Gordon Reeve—and two other people whom I can’t really remember. I had a wall where I had stuff that I wanted them to see. Gordon was firing questions at me in a language that I understand now but didn’t at the time and my patience was going. In those days juries came to the studio to interview you for the grant, and I thought, I have to be nice to these people, I have to say the right things. So I was really nervous. Anyway, he kept asking me this one question and I said, ‘Gordon, you’re going to have to ask that in a different way or not ask it any more because I don’t understand you at all.’ I thought, I’m not getting this grant, but I did. I got the grant to can the buttons. It started off the way our foremothers or fathers would have done, with a canner and jars, and then I thought, I don’t have to do this because that’s not what it’s about. It’s about saying something, it’s about art, it’s about what I want to do. So I would do anything I wanted with the jars. It didn’t matter.

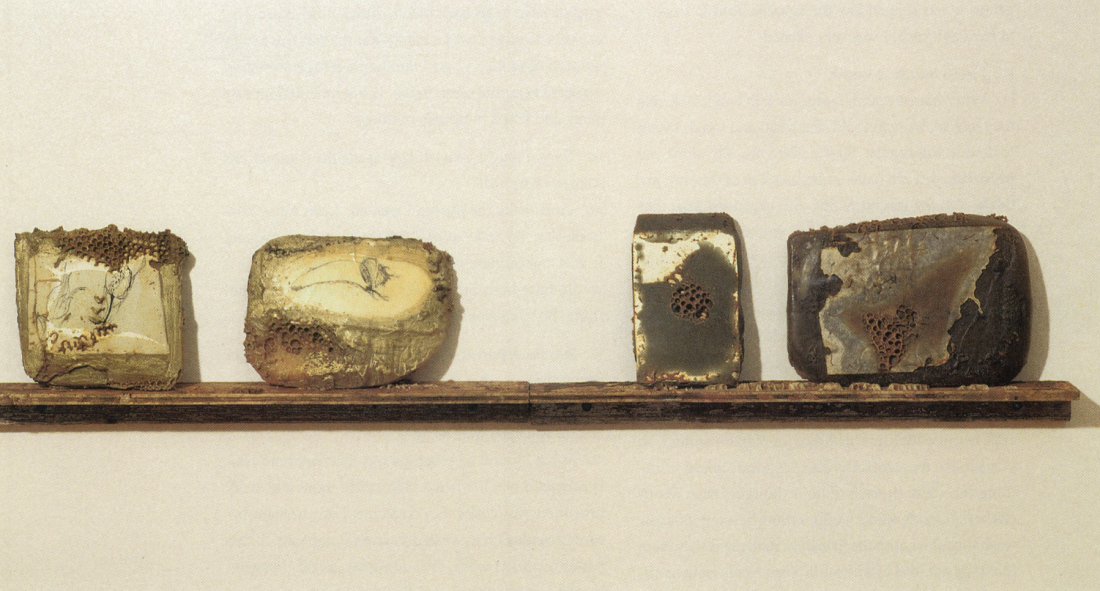

Tile Detail, 1998. Photograph: Guy L’Heureux.

Did you prepare the buttons? I mean, were they cooked or baked?

I baked them. I baked them in the house when Peter travelled and one day I started the oven on fire, which wasn’t very much fun. But luckily I had a very intelligent nine-year-old son who grabbed the fire extinguisher and put it out. My friend, who’s a psychologist, had phoned from Prince Albert and said, ‘Why don’t you make a button pie just to get yourself into the domestic mood?’ Anyway, that didn’t work. Then I had an uncle who was a scientist at the University of Manitoba and I phoned him and asked, why do these buttons start on fire? And he said, ‘Well, why don’t you research what chemical they’re made of?’ I told him that some of them smelled really bad, and he said, ‘You have to remember that not everything that stinks is bad for you and not everything that smells good is good for you.’ That was the end of his conversation. It was so bizarre, but he said they could be really dangerous, they could be toxic. Wanda would come to the studio and she’d say, ‘I don’t like the way it smells in here.’ So I’d throw out the plastic ones that were deteriorating.

Was there a point where you were able to put them unaltered into the jars?

Finally. It took a lot. I did everything to them I would do at home to prepare food, because I was taking what George had said literally: you can only be who you are and where you come from and what you know. And dammit, I was a really good homemaker. Honest, I really was. So I tried to do that in the studio, taking it to such an extreme, and it worked for me. Then after, I would invite people into the studio. People are generous in this community and I think if they know you’re serious about doing something, you can have great conversations.

Was there a point where you actually thought of yourself as an artist and recognized that the processes you were going through in the studio were artistic processes?

Yes, that point came. I think I had a drive that was beyond worrying. I wouldn’t have survived without art. They’d have to put me away, I couldn’t survive in a world where I couldn’t speak. It’s a way of saying something, it’s communication, and I couldn’t have done it at home. I just don’t know what I would do all day. I was also very fortunate that my husband, who is a European male, would ask what was wrong if I wasn’t ready to go into the studio in the morning, so he must have known that I had to go. So I did most days. I imagine that’s what all artists go through if they really want to be artists. Sometimes it scares me to think back. Our daughter said to me, ‘People used to come to our house and just couldn’t believe what was going on,’ and I said, ‘What was going on?’ You just don’t notice it when you’re in it, right? But I didn’t have time to worry about it. My mother got a lot of flak from her sewing circle. They’d say, ‘Everyone has shrunk clothes, what’s the matter with her?’ Stuff like that. It was hard on her. My dad came to Plug In to my exhibition one day, I remember. He was this tough guy and he said, ‘I come in here to see if this is art.’ My father knew nothing about art but knew a lot about life. He just wanted to make me feel solid about it.

Drawing table, studio. Photograph: William Eakin.

It seems to me that you have intuitively worked your way through a lot of your career. Your discovery of the bees was something you happened upon. Is that about luck or is it about how intelligently you operate on your intuition?

I don’t know because sometimes I just take something that’s in front of me. I think, why don’t I look beyond my own little world? but it usually connects to the larger world. I couldn’t find regular wax that’s used for candles, and because canning is a big deal in Manitoba, I couldn’t find the wax that the canners use. So somebody told me there was beeswax down the road. I went to the bee place where farmers bring their wax and above the manager’s door was a sign that said Bee Maid Honey, that’s their brand name, and it was in honeycomb text about four inches deep. And I looked at it and I thought, now I’ve met the people or the creatures I want to work with because they’re sculptors. So I went to all the bee events in town. You go to the mall when they’re selling honey, and they have all their products there. I noticed that beekeepers are really inventive people and they would try out all kind of things in the hive, and I was desperate to meet the man who made this sign. So I said to the manager at Bee Maid Honey, ‘I’d like to meet the man who does this.’ And he said, ‘Oh, he makes signs for his friends all the time.’ He said, ‘I’ll tell Gary when he comes in here with wax and I’ll call you and you can meet him.’ It took a long time, I was finishing off some artwork, and all of a sudden the manager called and told me Gary had made some signs for me like Gary Bee Art, Hi Aganetha and Think Honey Art. They were real signs. So I phoned him immediately and he taught me what he knew about making texts in the hives.

The way he communicated with you was by leaving you a bee-made message?

Yeah. It was really amazing because he didn’t know me at all, he didn’t know what I did. He just knew that somebody wanted to know how to make those signs. So Peter and I went down and spent a day with him and I learned a lot about how bees work. It reconfirmed all my thoughts that they worked like a sculptor does—they build and construct. Then I tried to read about their architecture and how strong it is. I learned that in Japan where they have earthquakes, the pillars they put in the ground are modelled on bee architecture. I was trying to find a reason for working with them. I decided to do it after I met Gary Hooper, and I went to the library to start researching bees and wax, and Louise May came into the library and asked what I was doing. When I told her, she said, ‘There’s a beekeeper out at SNACC. His name is Phil and he’s doing a degree in philosophy.’ I met Phil and began working with him right away. He’s just finished his Master’s degree on “Bees and Consciousness.” I went to his defense and listened to what he had to say and didn’t understand a word.

Bees altering a drawing, 1999. Photograph: William Eakin.

Were you still working with the buttons or had that exhausted itself? It sounds as if you were ready for the bees and that it was rather an abrupt shift.

No, I had completed the Library: Inner/Outer. I had wanted to finish it because I wanted to work with the bees. It was two years, trying to figure it out and experimenting. Phil let me use the hives after the beekeeping season ended on August 26. The beekeepers have to remove the honey and the bees have to be kept alive till freeze-up. So he let me use the hives in that time. I was teaching Artists in the Schools and I met beekeeper Henry Funk and he asked what I did as an artist, so I told him. And he said, ‘Come work with me.’ Beekeepers all want to work with an artist. I go to beekeepers’ picnics and get lots of information. They’re just very inventive people.

Do they want to work with artists because they understand the artfulness of what bees do? Is it that they have a natural affinity towards art?

I’m not sure. Unless they’re just a certain type of generous person. Since I made the glass dress I rent 10 hives every summer and I pay the beekeeper what he would get for honey. The nice part is that both Phil and Henry, whom I don’t work with very much—he’s an old-fashioned beekeeper, whereas Phil is right up there with the fanciest techniques—just leave me alone. If I want to use a certain material, I talk to Phil about it. He’s just a great guy, very young. And being a philosopher, he doesn’t say very much—he’s opposite to me. He told me, if you really want to learn something, just listen.

How were you able to distinguish in your mind, when you started collaborating with the bees, that what you were doing was still art? Had it changed because of the nature of the collaboration?

It changed because I couldn’t figure out who was making the art. The collaboration is really close and I’m terribly fond of the bees. And I don’t understand, it’s a language for me. I’m trying to understand interspecies communication, but it’s not clear yet. To give these insects or these animals the credit they deserve is really difficult as an artist. There’s a real tug in my head about that. Sometimes I put in an object and I’ve coated it with what I think will work and covered it where I don’t want them to work. I come back the next time and I find out they have made a decision for me. They’ve done something much better than I could ever have imagined. It’s on a totally different track. It’s a great thing. They chew my drawings up. Sometimes when I put a drawing in, they take away the part I thought should be torn up. But it’s a true collaboration with them because so much comes from them. So the beekeeper and I are observers of a sort.

Tiles on Hive Blankets, 1998. Photograph: William Eakin.

I remember you introduced brocade because you thought it would be lovely if they worked brocade. They worked it, all right, they chewed it up and spat it out. In the early years you didn’t know what they were going to do.

I do know what they will do now. I know what they will do on glass. I won’t give them leather or fur because it reminds them of mice or skunks. You don’t want to scare the bees or disrupt them. They don’t like corduroy, either. They also chew up plastic, so what I was doing was just making them work for nothing, which I don’t want to do. I’m trying to give them things that will matter. But I wonder how far this communication and collaboration will go before I’m not the artist at all. I don’t know how long I’ll work with the bees. Their language is quite amazing. They’re so warm and so tenacious.

Do you tend to anthropomorphize them? Do you see in them a farm of mechanistic humanity or is it that they are a different order of things?

They’re totally different.

Is The Extended Wedding Party the most ambitious piece you’ve done with bees?

It’s exhausting to think of it now. There was another collaboration in that project too—all the clothing that was sewn for that piece. Jake Moore came and helped. Wanda Koop’s mom—who storytold the whole time—and a lot of young artists, came to help. There’s no end to what you can do with bees. I just don’t know how long it’s going to work for us together. Could be for a long time, could be for the rest of my life. I don’t know.

The work that’s in the studio indicates a kind of archaeology in your relationship with the bees. It’s like the fragments are evidence of a relationship and a civilization that once existed. Do you see that as a possible reading of the work?

I guess I know how endangered they are, as endangered as we humans are. I mean, I don’t know how we’re most endangered, by pressing the red button of the bomb or through disease and our declining health. But the bees have so many enemies and now they have mites. Ninety-five percent of all the wild bees have died in the world. If it weren’t for the beekeeper, I don’t know where we’d be. They have mites: one mite eats the brain and the other one the contents of the bee’s stomach. And hives can go in days or overnight. Now they have a new bug that’s the size of a medium-sized cockroach. Phil says that if it comes into the apiary it eats the honey so the bees starve. I guess you could talk about it the same way we talk about global issues with humans. But I’m still really thinking of them since Manitoba is so filled with mites. What I started to do is ask the beekeepers to save me fragments from the hives that are deteriorating. So I’m collecting all those wooden things. I don’t know what to do with them but I think it’s going to become a little museum of pieces. I don’t see it as an end to the work but it might be.

Shoe, Beework, 1999. Photograph:William Eakin.

Do you still have this wonderful sensual relationship with the bees? Are they still as appealing to you as they originally were?

I think it started in 1989—about 10 or 11 years ago. I have great respect for them. I’m not afraid but I dress to the nines when I work with them. I’m also interested in the power of the small, including bacteria and viruses that are so tiny we can’t see them. Well, this little bee has so much power that if you’re allergic you could die from one sting. When I think of an entire hive, it’s almost too much power. Also the information that a drop of honey contains. I’m reading a book right now that says a drop of honey has the history of all bee kind. If you could analyse it, it would have all the information. The whole thing is so amazing: their sexuality, their mating, their dancing—all that is a closeness I don’t understand. And just to have a massage from the bees is the greatest thing I’ve ever done. I notice beekeepers will take a bee and put it on their hand. For a couple of years I thought, I wouldn’t do that, but they pick out the drones who can’t sting. There’s all these little things that you learn about the hive.

Have you been surprised by the acceptance of your work? Now you exhibit a good deal in Europe. What’s it like for you to take this work and these ideas into other cultures?

I think because the bees are a global creature, it doesn’t matter where you go. In Britain it was fascinating because they have different-sized hives and the strange part was they said they had swarm hives, but I didn’t know what that meant. What it meant was they were capturing these swarms to add to their apiary, so these swarms were very, very angry. I had my first attack by a swarm of bees. As I said, I always dress completely in respect to their capabilities. I don’t know what happened. The beekeepers were there. I never went to those hives by myself because I didn’t know the beekeepers, the bees or the process over there. The beekeeper opened the hive to see what they were doing with the work we’d introduced and they just went for us. They chased me for maybe half a mile and I kept going into the woods. They were in my socks, even though I had on wellies with elastic around them. I had been afraid the day or the week before, and I was giving a tour to a group from Leeds University, art people, and this is when I got chased. When I thought they were all gone, I felt I was crawling. My shoes were full of live bees, and because of the layers, the stingers weren’t in there. They died having stung me, but there were hundreds of bees in my feet. The rest of me was fine.

Aganetha Dyck working with bees on site, 1999. Photograph: Meeka Walsh.

You ran for half a mile?

At least half a mile. I was covered, just like a carpet. Everybody had to leave, it wasn’t only me. It was terribly itchy. I was swollen but luckily not allergic. After that we taped our boots. I haven’t had that experience ever in Canada. It was amazing. Then in Rotterdam I worked with a beekeeper who had bees in an old churchyard. They were very holy bees, Catholic, I think, maybe Protestant. Anyway, they’d lived in green hives. I used to take the train every morning, which I’d get on at seven o’clock. I’d get on the train because the studio was so cold. I would travel and if I would see bees on the side of the railroad and it was close enough to stop, I’d get off and visit the bees. Once I got off the train and I spent a whole afternoon at a hive, talking with a man who looked after the bees. It was connected to a church and I wish I’d had a camera because the churchyard was all pink apple blossoms. It was out of a postcard. It looked too beautiful.

The drawing that you’re doing of the bee’s leg is really fine. I know you mentioned studying drawing with George Glenn in Prince Albert. But have you always drawn?

All the time. I’ve never shown the drawings because I always felt that I couldn’t draw. I know I can, but because I probably couldn’t draw you in the chair—you wouldn’t look right—I thought I couldn’t draw. Now I know I can draw because it’s like any other art. It’s what we make. I draw all the time.

Since you’ve been working with bees, have the drawings been primarily about bees and other insects?

Bees. When I was in Amsterdam I found a book which has a drawing of a bee and I make that drawing all the time. I’m getting really good at it too. I copy it. In the book the bee is much smaller, a quarter-inch or something. So I draw that bee every day. A bee a day because it’s such a wonderful drawing. The book drawing is sort of naïve—the bee has only three legs—and that suits how I draw, as well. Sometimes I just look at books and I also use a magnifying glass. But I have to get a microscope so that I can properly draw what I want.

Aganetha Dyck working with bees on site, 1999. Photograph: Meeka Walsh.

Do you conjure up the spirit of the bee every day? Is it a daily ritual, like bathing or like praying?

Sometimes in summer I don’t because I’m there with the bees, but in winter my only connection to the bees is to draw some part of them. I find some of the bee parts very sensuous and absolutely amazing. I think I’ve drawn all the bee parts, mostly from textbooks. Because I don’t have a good enough microscope, I sometimes can’t find a part on the bee, so I keep telling the kids that a good microscope would be a nice idea for my next birthday. You can do blind drawing while you’re looking in the microscope. It’s also a wonderful way of thinking when you’re drawing—figuring things out, coming to your next step.

Do you know what the next step actually will be with the bees? You say you don’t know if you’ll always work with them, but do you know what the next project is?

It’s continuing with the language and with the Braille, even though I don’t understand and can’t read it. I went to the CNIB and they said it would take a minimum of two years to learn Braille. I have lots of information but it’s like the language of the bees, I don’t understand it at all. Then I’d like to talk to bacteria, something even smaller.

Is it a question of wanting to understand smaller and smaller things and making them visible to us? You draw the bee’s leg in a scale that is large enough for us to actually see what it looks like. Is it about shifting the scale so we can actually read what the bee body is?

It could be, I’ve just started this series with the legs. I’ve drawn the stinger and all the different parts. I think I drew legs because they are important in society. I don’t know what I’m going to do with this “Rosetta stone” these big slabs of beeswax. I’m going to have them transcribed into Braille. It’s about breaking codes, cracking codes, and it seems like something society is really interested in understanding. I’ll show you the hive blanket—the blanket is like a hieroglyph. It may be that I’ll put a hive blanket in the hive. That won’t be a stone or a slab of wax. But I have to think of the material and I have to think of the process. That’s what I’m working on, but I have no idea how it’s going to happen. I’m also working on seeing light through them. You know, the bees’ flight patterns are basically drawings.

Aganetha Dyck working with bees on site, 1999. Photograph: Meeka Walsh.

They’re minimalist drawings like everything else the bee does.

When I make those drawings, they are as intricate to me as the leg and just as important. So when you watch the dance and flight patterns, you’re trying to get that from your pen onto your paper. For the longest time I didn’t know what intuition meant. I used to think that it was just luck. If you created something that was considered successful in the art world it was just one of those lucky things in your life. And I always thought that a person who worked intuitively wasn’t a thinking person. People would say, ‘Boy, you work so intuitively.’ No I don’t. I really do think about what I am doing. So it’s taken me more than 20 years to realize this is where I am and this is what I’m doing. It’s very complex.

Your work is research in one way, isn’t it? It’s a kind of exploration.

I think I explore a lot. You definitely explore because you don’t know what you’re trying to find out. I think I was very afraid. But I don’t know how passion works over fear. It overrides it, doesn’t it? Because you’re never self-taught. I wasn’t sitting in a room all by myself, coming up with things. I’m exchanging ideas all the time. I think that’s what I do with the bees, I exchange all the time. They’re pretty amazing. When you go to an apiary you’re leaving your space and you’re going somewhere where very few people go. Not everybody walks into that space. ■