“The Great Parade: Portrait of the Artist as Clown,” edited by Jean Clair

This tome-thick collection of glossy plates and intriguing essays, meant as a catalogue companion to the exhibition of the same name, which opened in March 2004 at Les Galeries nationales du Grand Palais in Paris and is now running at the National Gallery of Canada till this September 19th, is sensationally capable of standing on its own as a book of wonders. It is so frightfully packed with riches from the disciplines of painting, photography, sculpture, film and criticism that one can only express awe at the scope and impact of the work assembled within its pages.

The exhibition takes its name from the famous painted ballet curtain Picasso peopled with classic clowns Harlequin and Pierrot, among other circus figures, for the 1917 Ballet Russes production of Satie’s Parade. National Gallery Director Pierre Théberge writes in his foreword how he was struck by the allegorical power these commedia dell’arte characters held for the roiling Spanish genius, and the ways in which they stood for “the many roles of the artist himself: critic, dissenter, outcast, wanderer, enchanter, acrobat, clown.” Eventually, Théberge and curator Jean Clair took the continual fascination among 19th- and 20th-century artists with the circus and its habitués as the subject of this vast and, at times, mystical study of the inexhaustible relationship between creator and clown.

The resulting collection boasts 211 pieces lent out to the show (all reproduced in the book alongside insightful and informative notes), work executed by the period’s greatest names in European and North American art, and which engages the saltimbanque and his enchanted environments to seduce the beholder with ineffable but palpable varieties of strange influence. Diverse visionaries bending their eyes toward the sideshow include Fuseli, Ensor, Arbus, Goya, Beckmann, Léger, Chagall, Doré, Sherman, Hopper and Dix, to name just some.

I’ve often read that filmmaker Josef von Sternberg studied the work of Belgian painter and lithographer Félicien Rops while prepping his great film The Blue Angel. Here is the proof. In Rops’s Venus and Cupid: Love Blowing His Nose, c.1878, we see the source of Sternberg’s backstage atmospheres, almost plagiarized in the film made a half-century later. An enigmatic Pierrot peeks out from the parting of a shabby doorway curtain, as in the film, to peer upon the deal-board toilette of “Venus,” a haunchy, topless showgirl purchasing with her fleshy flanks a firm grip on the edge of a costume trunk, the better to sit and supervise the nose-blowing of “Cupid,” a young boy decked out in sad, flimsy stage wings. The rancid artifice of these two burlesque gods and the thick, white, effacing makeup on the clown’s face load the latter’s voyeurism with all the leering lechery we hope we’re concealing while viewing this work ourselves. This moth-eaten comic cheerfully or ruefully sponges our own sleaze out and into himself, granting us an undeserved ennoblement in the presence of this picture, which we can enjoy alongside our lubricious enervation.

In work after work, dynamics of inscrutable carnival concatenation cast their antipodal spells. An uncredited photo portrait of Toulouse-Lautrec wearing the ruffled collar and conical hat of famed French funnyman Footit, but otherwise wearing his regular pince-nez and no makeup, seems to acknowledge this famed painter’s awareness of himself as a public figure poised halfway between important innovator and ridiculous buffoon.

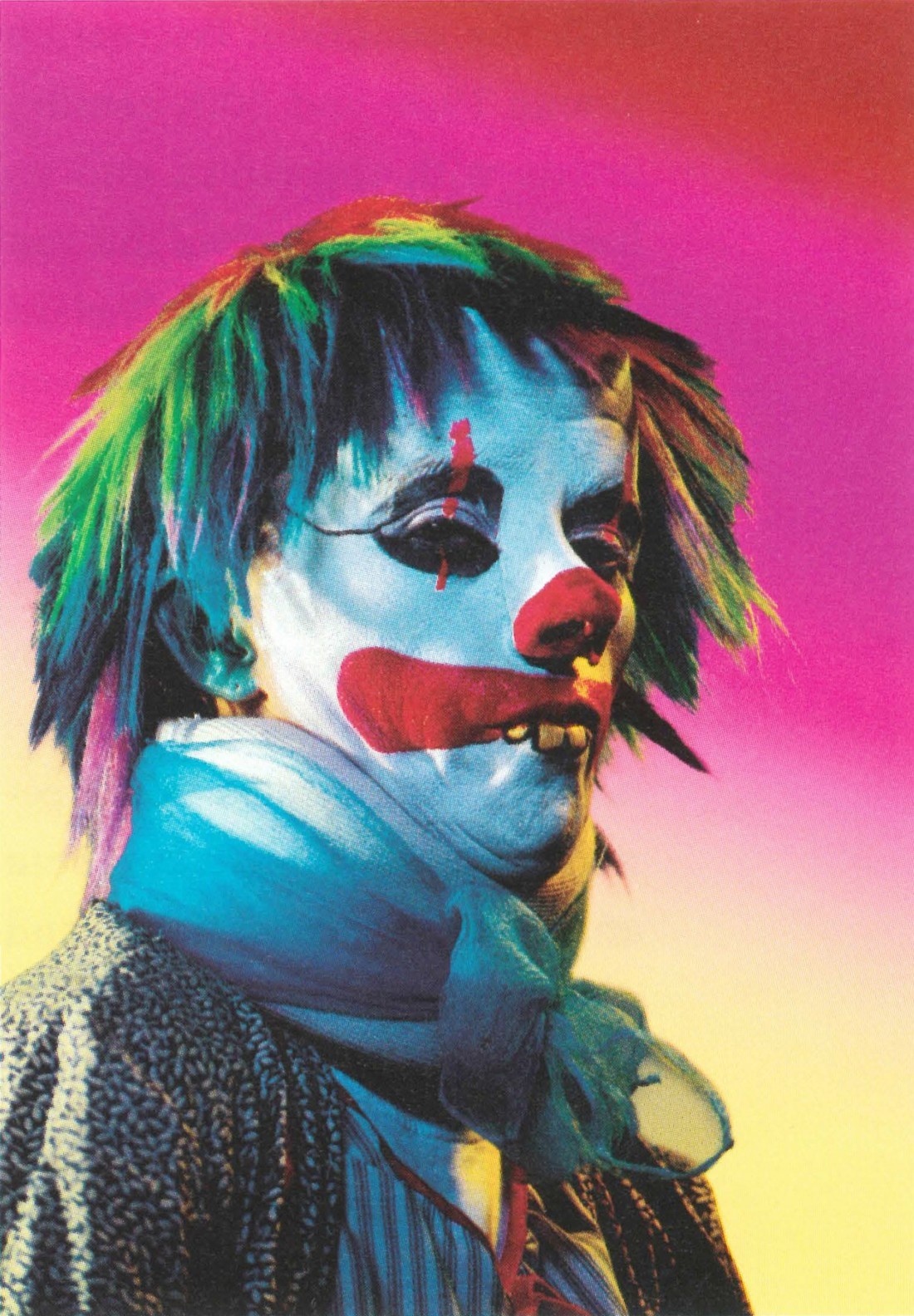

Cindy Sherman, Untitled 411, 2003, Dye coupler print, 114.9 x 79 cm. with frame. Courtesy the artist and Metro Pictures, New York. Photograph: the National Gallery of Canada.

We see a self-portrait by composer Arnold Schoenberg—one of some 60 paintings, or “Visions,” he made while studying himself in the mirror, scrutinizing the face at length until his features blurred for him, and for his brush too, leaving a sort of smudged mask with, instead of a mask’s empty holes, the piercing gaze of his eyes. The expressionist rendering of these eyes is suggestive of the emotion-heightening qualities of greasepaint used by vaudevillians, and the viewer quickly abandons the search for Schoenberg’s likeness in the portrayal, which gently mutates into the representation of an unknowable, melancholy clown.

Austrian-American photographer Lisette Model’s Alberta-Alberta, Hubert’s 42nd Street Flea Circus images, 1945, featuring a “half-man, half woman,” and her action snap of a nocturnal circus foot race run by men dressed in oversized bird costumes—the fastest, a sensational dodo helped along by an invalid’s cane—seem to grope alongside the hallucinations of contemporary night seer Weegee for the same black juices that one day would succour Diane Arbus. (On another page, Weegee himself shows up painted and apparelled in Barnum livery, wielding his infrared flash in pursuit of a masked colleague across some urine-soaked sawdust.)

Bent on arresting popular as well as high-brow entertainments on canvas, Edgar Degas inverts the habitual downward ogle with which he ogled ballerinas in order to capture the airborne arcs of a fetching acrobat, a ballerina of the air, in his Miss Lala at the Cirque Fernando.

The singular Alexander Calder sculpts from wire, working miniature circuses that he demonstrates as a most charming ringleader in mufti starring in a film directed by Frenchman Carlos Vilardebo in 1961, from which The Great Parade extracted some stills.

Alexandr Rodchenko manages to sneak a little mischief into his work, during a time of extreme personal repression by the state, with his uncanny photograph of Soviet clown Vitaly Laserenko—even Rodchenko’s camera seemed to see the world and arrange its shadows in kinetic Constructivist terms!

Picabia, Klee, Duchamp, Capa and Beuys! All in thrall at one time or another to the clown and his environs. These artists explore their mischievous and malignant ways back through the work in this overspilling collection to the ancient pathways of the jester in hope of finding the secret court space from within which they can best view their bemused audience, the world. As part of this chortling, queasy world, I am excited to be given the reverse prospect this invaluable book affords. Hold it in your hands and laugh! ■

The Great Parade: Portrait of the Artist as Clown, edited by Jean Clair; New Haven and London: Yale University Press, in association with the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, 2004, hardcover, 424 pp, $75.

Guy Maddin’s latest film is The Saddest Music in the World.