“The Durable Idiom”

Calgary’s TrépanierBaer is a commercial art gallery that curates its shows, making juxtapositions that are most often unexpected—for example, sculptors Evan Penny and Stephan Balkenhol or painters Carol Wainio and Ron Moppett—and that produces relationships among artworks in the inventory that are worth thinking about. Last spring Yves Trépanier, who had been ruminating on abstractionists in the gallery stable, brought out works by Eric Cameron, Christian Eckart and Stephane LaRue in an exhibition called “The Durable Idiom.” These are three very different artists, but the nature of the works and their complex interplay not only presented the opportunity for a pleasurable and fruitful game of compare and contrast, it also went a long way toward showing why some varieties of abstract art have had such long lives.

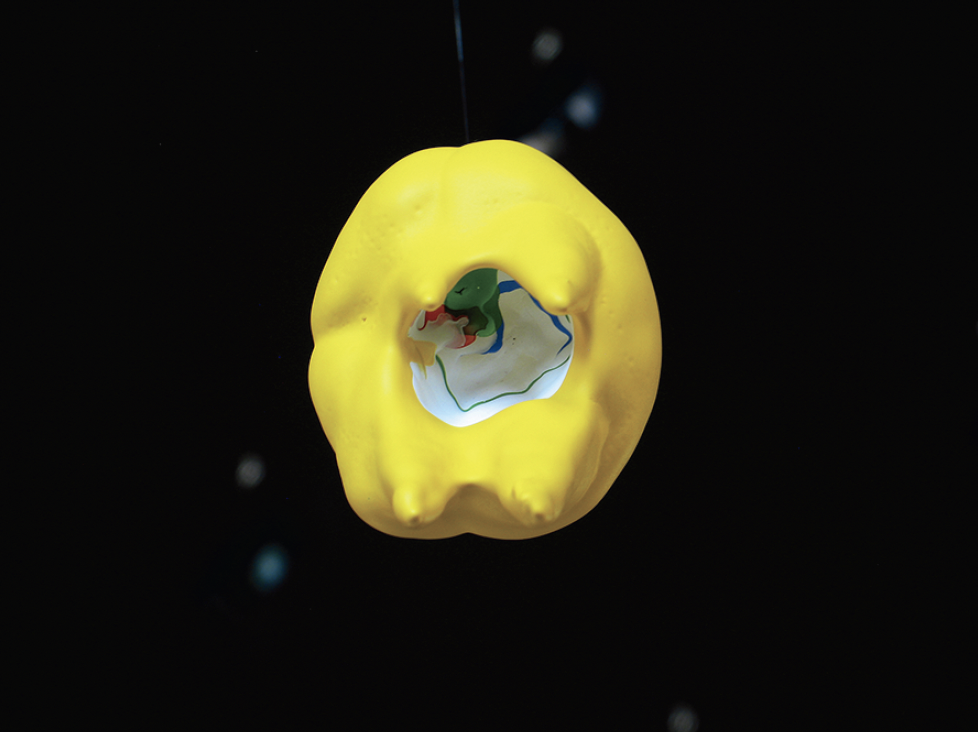

Eric Cameron, Thanatos 81, 2010-2011, latex on Remembrance Day poppy, dimensions variable. Courtesy TrépanierBaer Gallery, Calgary.

The news in the exhibition was Eric Cameron’s “Thanatos,” 2011, a new installation of 100 “Dipped Paintings” that hung in square formation, 10 by 10, about 86 inches above the floor, like a strange upside-down garden. One looked upward into these brightly coloured organic forms, which were each suspended from a 100-yard spool of fishing line. Cameron created them by dipping Remembrance Day poppies into vivid hues of Expressions latex paint multiple times and choosing a different colour for each layer. The two-dimensional plastic poppies slowly became thick and bulbous, with latex stalactites (or depending on their orientation, stalagmites) on the peripheries of their open inner cores. Like real flowers, the transformed poppies display aspects that are both male and female.

The female concavities are the unexpected effects of the dipping process, which initially built up downward-pointing convex surfaces. But, Cameron explains, “as the paint accumulated through repeated dippings and spilled over the edge, the undersurface became increasingly concave until a point was reached where the developing air pocket underneath prevented the paint reaching every part of the undersurface. All sorts of strange configurations of form (and colour) began to appear and would continue to develop until the tube of hardened paint underneath each poppy became so long the liquid paint could no longer reach any part of the concave undersurface. The results took me completely by surprise…”

Christian Eckart, Square Monochrome Painting, 1989-2011, acrylic urethene on aluminum, 60 x 60.” Courtesy John Dean and TrépanierBaer Gallery, Calgary.

By this time, Cameron had refined his methods for making “Dipped Paintings,” which he had begun years earlier because they took less time and labour to make than the “Thick Paintings” for which he is best known. Whereas the “Dipped Paintings” are made by lowering an object into liquid paint and pulling it out, the “Thick Paintings” are made by painting an object with hundreds of alternating layers of grey and white gesso. As the layers accumulate, the “Thick Paintings” begin to take on their own elaborate, aberrant shapes. The point at which Cameron loses the ability to make the works in either series conform to his intentions or expectations occurs because invisible natural forces of gravity and physics have taken over and have begun to act upon his fluid materials, eventually far exceeding the template of the underlying object.

“In each case, my first response was to try and eliminate the uninvited disruptions of the initially intended outcomes, until I came to recognize that the failure of my personal will represented a triumph of natural forces latent in art materials that had far greater and far more subtle potential for invention and expression than any contrivance of outcome I might aspire to. To explain what happened, I devised the terms ‘material mysticism’ for the process and ‘mystical materialism’ for the theory I built up around it.”

An emphatic materiality, albeit achieved by varying means, is common to all of the work shown in “The Durable Idiom,” a materiality so emphatic that it produces the painting-as-object. Cameron does this with innumerable coats of gesso or paint applied by hand to everyday objects that are subsumed into seemingly fantastical baroque manifestations. Christian Eckart employs sleek minimalist shapes that most often are manufactured in metals like aluminum or mirror-polished stainless steel, and coated with layers of hand-rubbed automobile lacquer or high-tech industrial paints. Stephane La Rue works with mostly natural materials such as birch plywood, linen or cotton, graphite and gesso to produce eye-twisting perceptual illusions of space in flat planes. He is the most traditional painter in the exhibition.

Stéphane La Rue, Intersections No. 2, 2010 (Detail 2), graphite powder on pine plywood, 14.33” x 24.5” (approx). Courtesy TrépanierBaer Gallery, Calgary.

For both Cameron and Eckart, the painting-as-object presents itself as a means by which to gain access to the invisible world that lies beyond the material world, call it the metaphysical, the spiritual, the divine or an alternate universe. Through his artistic labour, Cameron becomes a conduit for this invisible energy that is then embodied by his work. But if Cameron is the direct agent of mystical materialism, Eckart, who refers to himself as an “icon painter,” a maker of devotional objects, is more the archaeologist. His paintings are a kind of meta-painting, that is “an of or about painting.” What he questions and probes is the manner in which painting does or can address the primal human hunger for contact with the divine and for transformation and transcendence seen across centuries of art from the medieval times to the present.

La Rue’s spare and elegant paintings, by contrast, seemed entirely secular and formal, objects devoted to the history of minimalism and Modernism. In the 20th century, art displaced religion for true believers in abstraction. In the 21st, La Rue puts his faith in painting and the briefer glimpse into the sublime when suddenly a plane shifts and a space opens in a material object that is earthbound. ❚

“The Durable Idiom” was exhibited at the TrépanierBaer Gallery in Calgary from March 26 to April 23, 2011.

Nancy Tousley is an art critic, journalist and independent curator.