The Downtown Show

There’s an uneasy freedom inherent in not being considered part of America, something New Yorkers realized on October 30, 1975, when their bankrupt city was denied federal aid and The Daily News tabloid ran the infamous headline, “Ford to City: ‘Drop Dead!’” President Ford’s fake statement would echo a truth to the city’s artists, who felt it not only as the country’s opinion of New York but as uptown’s opinion of downtown and its younger, poorer, desperate generation making art out of anything. A few months later, the Ramones’s first album—a perfect marriage of pastiche and minimalism—made all that came before it sound tedious. It would be a clarion call that started a decade’s worth of invention and purpose, until Reagan’s re-election in 1984 and the establishment of New York as avarice central.

David Wojnarowicz, Untitled, from the series “Rimbaud in New York,” 1977-79, gelatin silver print. David Wojnarowicz Papers, Fales Library and Special Collections, New York University. Courtesy the Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh.

Without romanticizing hell-on-earth living conditions, Paper magazine editor Carlo McCormick’s “The Downtown Show: the New York Art Scene, 1974-84” presents a stunning version of the city’s worst years, through the works of 175 artists whose work made evident how flatlining finances, coupled with nascent and new languages, resulted in a defining moment for art and culture. Political in its scope, the show speaks of a time when artists and classes who had never communicated before were all pushed into the same squatted storefronts by circumstances best summed up by Vito Acconci’s 1976 installation Where We Are Now. With a boardroom table extended as a gangplank through an open window storeys above the street, Acconci’s work is as detailed a fiscal report as is needed, and photos from it are placed in a perfect gesture of nihilism at the beginning of the show.

Large and unwieldy blocks of time past are ripe for the ham-handed reductions and glib wall cards that often turn big exhibitions into lifeless kiosks, but “The Downtown Show” has turned the unwieldy to an advantage. The result is something cramped, complex, loving, messy and brilliant—like a neighbourhood. Rather than ordered chronologically, the work is divided into thematic salons. That’s a problematic approach, but the selection is done with permeable borders, allowing the influence of previous eras and transformations into the thesis. Within 10 feet of the “Body Politics” salon we go from documentation of Carolee Schneemann’s Interior Scroll performance—a moment marking a joyful, feminist break from the structuralist 1960s—to the Georges Bataille-inspired burlesque of Karen Finley’s I Like the Dwarf on the Table When I Give Him Head and its intuiting of the effects of Reaganomics and conservatism on 1980s bodies under siege from poverty and HIV.

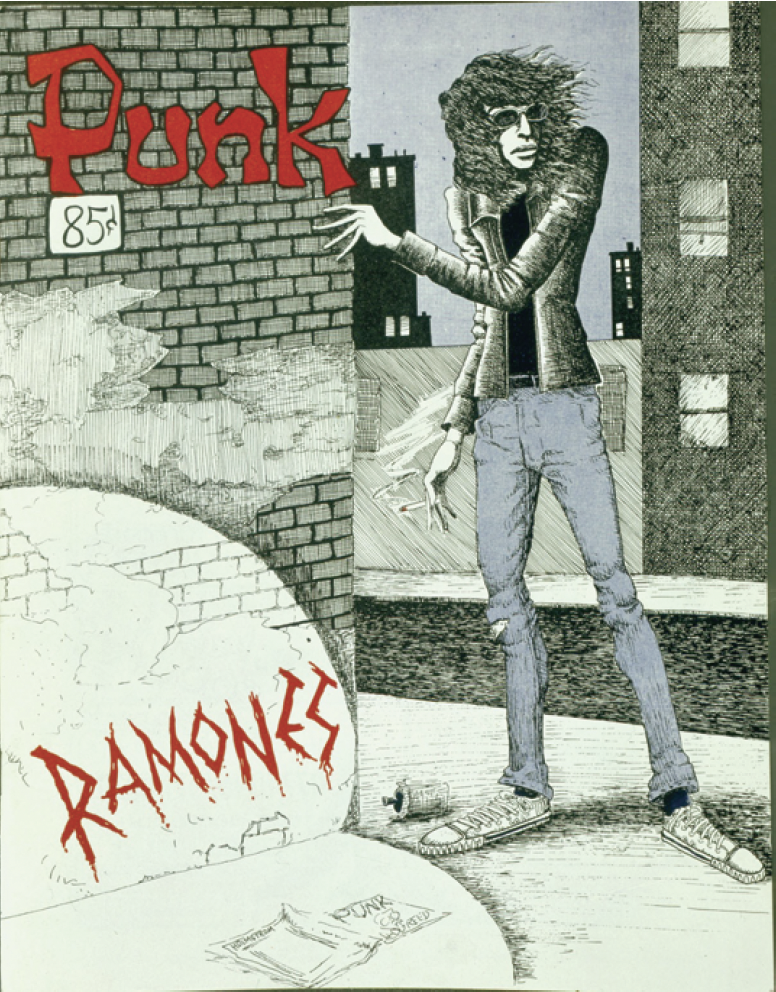

Front cover of Punk magazine, no. 3, April 1976. Fales Library and Special Collections, New York University.

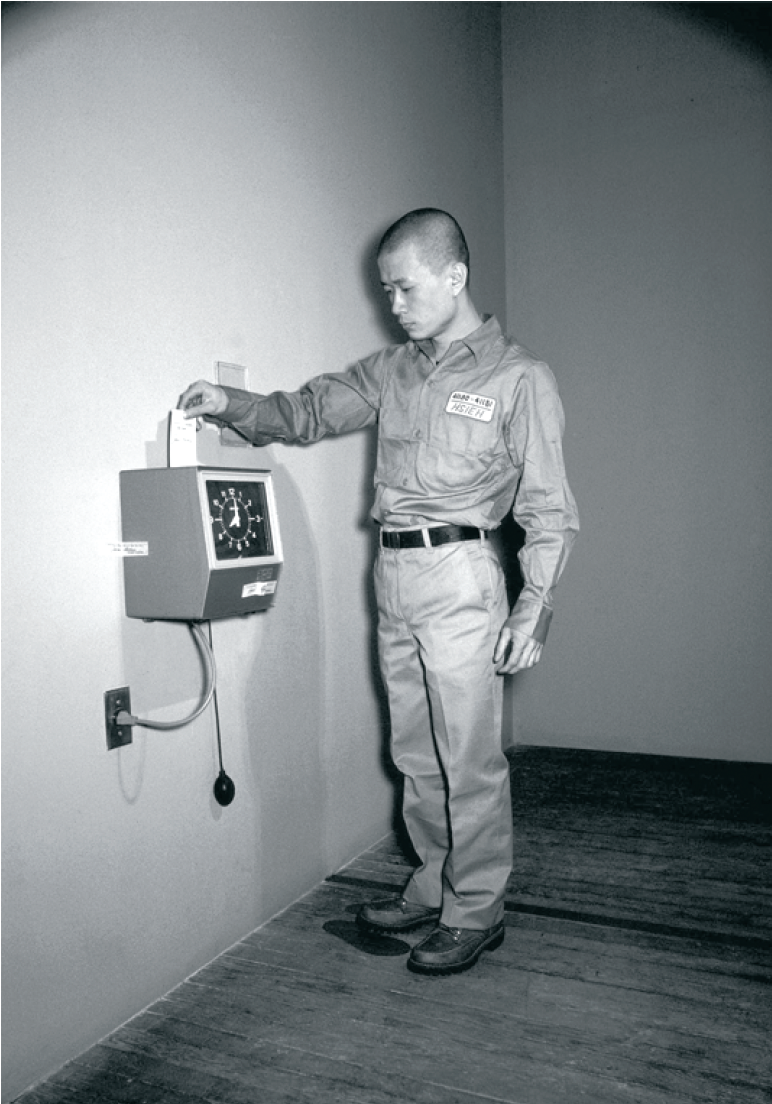

Still sorting out the 1960s in a way, the “Sublime Time” salon assembles the Zen slapstick of Jack Goldstein’s Suite of Nine 7-inch Records with Sound Effects and Tehching Hsieh’s One Year Performance (Time Piece) as progressions away from the supercilious austerity of minimalism. For all the lines it suggests, the exhibition’s secret is to draw outside of them. Several artists float from one section to another, and punk, in the form of flyers and constant soundtrack, is a note that hovers through it all—perhaps a little too much. In a gallery context, punk always carries the sad air of a zoo animal about it. But if one artist seemed to embody downtown’s hybrid fabric it was the late David Wojnarowicz, included here no less than four times. His mediums were a thief’s kit of Super 8, stencils and photography, and his work, such as the “Rimbaud in New York” series, was always autobiographical, political, but never easy.

“The Mock Shop” salon is the only misstep. By accident or design, it haphazardly connects the avantbusiness sensibility of Fluxus to the unreconstructed kitsch of Keith Haring’s Pop Shop, and in between is Jeff Koon’s vacuum cleaner and his clumsy stockbroker’s whimsy. But “The Downtown Show” is more than capable of auto-critique. With professionalism and high rents displacing smarts and free spaces, the scene began to respond. In the “De-Signs” salon of public detournements and street art, Jenny Holzer’s sign work It Takes a While Before You Can Step Over Inert Bodies and Go Ahead With What You Were Trying to Do retains its power. A witty and terribly functional chart titled Art for the Evicted, created for street posting by the Not for Sale Committee, compares the increases in rent on a single block as wine bars and galleries move in. It’s a harbinger of the party’s slow ending.

Tehching Hsieh, One Year Performance (Time Piece), New York, April 11 1980 to April 11, 1981. Courtesy the artist.

As a closing salon, “Broken Stories,” goes the farthest towards resisting nostalgia. In collecting Kathy Acker chapbooks alongside Richard Prince prints with the videos Record Players by Christian Marclay and Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman by Dara Birnbaum, McCormick succeeds in drawing out what these years left to artistic practice: the ability to mine narrative for lies and truth at will, and to turn away from art history as a given and confront dangerous and new instabilities. Basically, what the lazy would call “postmodern.”

While “The Downtown Show” is profoundly complete (the only thing missing is Michael Musto trapped in a vitrine) there’s a satisfying vagueness to its conclusions. In naming the show with hyphenated dates, a simplistic answer, for those who want one, is already provided: It’s over. The economic conditions that created it are gone, or just exported to the developing world for the time being. With the Internet radically reworking the notion of community, art can look beyond “Bohemia” to new definitions of locality. Those years, that town, did their job. Now, in the words of one punk who still ends his performances this way: “Go start your own band.” And that is the mission with which one leaves “The Downtown Show.” ■

“The Downtown Show: the New York Art Scene, 1974-84” was on display at The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, from May 27 to October 22, 2006. It is currently on display on the Austin Museum of Art, Austin, Texas, until January 28, 2007.

Brian Joseph Davis is an artist and writer living in Toronto. His most recent work has included the “Yesterduh” project at Mercer Union and the founding of the Centre for Culture and Leisure No. 1.