The Contradictorian

An Interview with Alanis Obomsawin

We live by the stories we’re told, and we live to tell stories. The stories that Alanis Obomsawin heard about her Abenaki people, and about herself, when she was nine years old and the only Indigenous child in a school in Trois- Rivières, Quebec, was that she belonged to a savage race of liars and murderers. That was textbook Canadian history, accepted as truth and taught by the Catholic Church. What began to dawn on her at the time, and what later became apparent to her as a singer, performer and filmmaker, was that it was necessary to present alternative stories about “Indians” in ways that were not destructive and punishing. The production of these new, truthful and celebratory stories became her life’s work. Throughout her “distinguished” (my inclination is to move closer to something like “legendary”) career she has focused on educating, in the broadest sense of the term, a viewing public about the lives of Indigenous people across Canada. “I’m always thinking of teaching,” she says in the following interview, “information is very important and it has to be accurate.” She describes this process simply as “my way of working.”

Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance, 1993, dir. Alanis Obomsawin. Photo: Shaney Komulainen. © 1990 Shaney Komulainen. All rights reserved. Courtesy National Film Board of Canada.

Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance, 1993, dir. Alanis Obomsawin. Photo: Shaney Komulainen. © 1990 Shaney Komulainen. All rights reserved. Courtesy National Film Board of Canada.

That way of working resulted in her first film with the National Film Board (NFB), an enchanting 13-minute-long documentary about children called Christmas at Moose Factory in 1971. It’s accurate to say that children are her favourite subjects; her films often feature the complications of their lives, and she has made a cycle of films on children’s welfare and rights. Christmas at Moose Factory was an auspicious introduction, and it signalled the beginning of a career that now includes 60 additional films.

The most recognized was Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance, 1993, her dramatic documentary on the Oka Crisis, when Canada teetered on the edge of a cultural war in a 78-day standoff between Mohawk warriors and the Canadian army. Obomsawin was filming inside the blockade and her memory remains clear about how that felt. “If I were to tell you that I wasn’t afraid, I’d be lying. … it was very dangerous.”

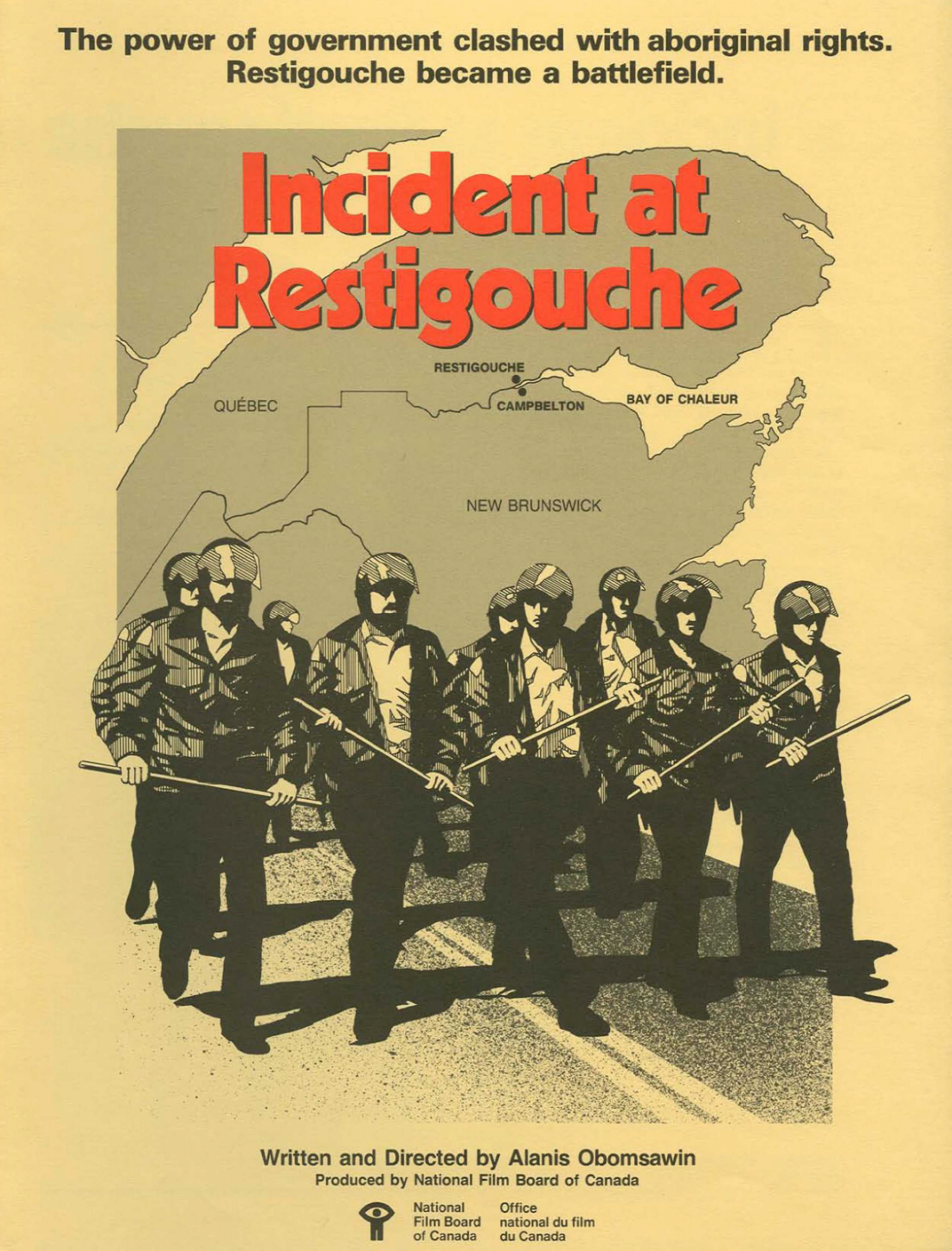

Obomsawin consistently brings a passionate intensity to all her films, whether one-minute vignettes about wild rice harvesting in Kenora and throat singing in Povungnituk, or seven-minute short documentaries on canoe making by an Atikamekw Elder in Quebec or basket weaving among the interior Coast Salish in British Columbia. Her documentaries on the politics of salmon fishing rights among the Mi’kmaq of Restigouche, Quebec (Incident at Restigouche, 1984), and contested fishing and hunting rights in Burnt Church, New Brunswick (Is the Crown at War with Us?, 2002), are among her most persuasive and telling films; what they reveal is how often provincial and federal governments make decisions based on systemic racism. The title for her 96-minutelong feature about the Mi’kmaq in Burnt Church is framed in the interrogative. The naming asks that rhetorical question.

Nowhere is the gap between Indigenous and settler attitudes more apparent than in an interview Obomsawin conducts in her own home with Lucien Lessard, the fisheries minister for the Province of Quebec in 2000, who ordered 550 armed members of the provincial police into the community to make arrests. Obomsawin is an advocacy filmmaker, but in this dialogue her normal position as discreet interviewer turns into the accelerated role of an unstoppable interrogator. Lessard appears condescending, foolish and equivocating, and Alanis forcefully makes his lack of sophistication and unacknowledged racism apparent to any viewer of the film. It is an extraordinary encounter and should be a textbook case for any journalist and filmmaker who wants to learn the dynamics of how an interview can be conducted. (It can be seen on the NFB’s website, where most of Obomsawin’s films are available for viewing.)

Obomsawin regards words and the sound they make as “sacred.” Her quest to set in place words used in new ways, whether spoken, written or heard, involves the creation of new narratives, narratives in opposition to established colonial tellings. Her stories are not simply opposed to convention; they are complete contra-dictions. She is not against the practice of diction; she is just firmly committed to changing the words in the story. That is one measure of what she is against. In that respect, she is this country’s most eloquent and influential contradictorian.

Alanis Obomsawin’s exhibition “The Children Have to Hear Another Story” first showed at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, from January to April of this year, and will travel to the Vancouver Art Gallery and then to the Art Museum at the University of Toronto through 2023. It is accompanied by a 272-page exhibition book/catalogue called Alanis Obomsawin: Lifework.

The following interview was conducted by phone to Alanis Obomsawin’s office at the National Film Board in Montreal on July 5, 2022.

Border Crossings: I’m interested in the origin of your passion for storytelling.

Alanis Obomsawin: It comes from where I come from. When I was a young girl, my community didn’t have running water or electricity, and at night we’d use oil lamps and sit around the kitchen listening to the adults speak. Where I come from in Odanak, all the men would take off in the fall and go guiding for hunting and fishing, so when they told stories there were many encounters with animals. It was something that we really loved to hear. I heard lots of stories, but we didn’t have any images, so we imagined them. If you had three or four children listening to one story, you had four or three stories right there because each child imagined it in a different way. Storytelling has been with our people for thousands of years, and in all our communities in all the different nations, it has been a way of entertaining and teaching. That’s how you know your history.

Did Théophile Panadis have an influence on you? He himself was a storyteller and a dancer.

Oh, yes. He’s the one who taught me singing and lots of stories. He was my mother’s cousin and quite special to me. He also was very traditional. He spoke the language very well, as did my mother. I never learned English before I was 22 years old. It was a different time.

You joined the National Film Board in 1967. What was it like as a young woman to work at that institution in the late sixties?

It was difficult in a lot of ways. First of all, it was really a man’s world. Every time there was a problem, I thought it was because I was an Indian, but I never realized that being a woman was an extra problem. The main thing was that I really believed in what I was doing and I was so passionate about it. It came from the singing at first because that’s the way I fought back, and through that medium I was able to tell a lot of stories. So when I came into films I knew nothing about filmmaking. I learned here, which I do appreciate.

Christmas at Moose Factory, 1971, dir. Alanis Obomsawin. Photo: taken from the production. © 1971 National Film Board of Canada. All rights reserved.

It’s not until 1971 that you make Christmas at Moose Factory, a captivating, 13-minute-long film about the children in that community. What caused the four-year delay?

It didn’t happen like that. I went to Moose Factory in 1968 the first time and I gathered material through 1970. In those days the Film Board didn’t give me money, but they would match what I raised on my own. It was really very difficult.

You were the first Indigenous woman to direct a film there. Were you aware that you were making history in the position you had at the National Film Board?

I wasn’t thinking like that. I was fighting all the time for everything I did, every step of the way. I was doing it in the wildest way possible. But I was so sure of what I was doing, and for me the main thing was to get our people and our voice into the classrooms.

Was there something about documentary as a form for storytelling that you found particularly congenial? Was it suited to Indigenous storytelling because you could actually control the narrative for the first time?

It wasn’t exactly like that. There was a studio at the Film Board in those days called Multimedia. Everything that studio made was for teaching, and in classrooms they were using film strips. I wanted to get our voice in there. Through the Multimedia studio, I did these two educational kits in three languages. For me, that’s the best decision I’ve ever made.

You have talked about the difficulty you had in school as a child and how you ultimately had to physically fight the children who were tormenting you.

Yes. For the longest time I never did anything to defend myself. I was the only Indian in the school. In the classroom every time the teacher opened her book and said “L’Histoire du Canada,” I knew I was going to get beaten up that day. The classroom teaching focused on how awful we were; we were savages. We went around scalping poor white people who came here. This is what they were teaching. I realized that our children had to hear another story. That’s how I started singing and telling stories. I started with Scouts actually and eventually I made it to the school. So that took a long time, but it was incredible. That’s when I started doing these kits and it was a lot of hard work. It was the voice of a community. The first one was Manawan, Atikamekw next, and then French and English. It meant that it could go into any classroom. I was in heaven when I came out with those kits because now it was our voices in the classroom and the stories we were hearing didn’t put down our people and make them invisible like they always had been.

Christmas at Moose Factory, 1971, dir. Alanis Obomsawin. Photo: taken from the production. © 1971 National Film Board of Canada. All rights reserved.

You’ve said that in making films you were “pleasing your ancestors.”

Yes, because it’s the story. We are storytellers for thousands of years. And it was us telling it, not a book written, in this case, by the Church. It was written by Catholic Brothers and I’m telling you, it was really racist. That’s when I realized that the hatred the children in school had towards me wasn’t something they were born with; they were taught to hate. And then you realize this is very serious. So I thought all the children have to hear another story. This is how I made up my battle. I did hundreds of schools over the years before making films.

You got to know John Grierson at the NFB, didn’t you?

Yes. He was teaching at McGill in the ’70s and he encouraged me a lot. I’d tell him about my experience in the classroom and he was very excited about it. I got to know what an incredible person he was. He wanted people to be able to go to the movies and see themselves, instead of seeing beautiful, rich people you could never identify with coming down stairways. It was his idea that poor people, and in this case Indigenous people, should be able to watch themselves because they have life and they are part of life. He was influential in persuading Mackenzie King to start a film unit here. He did the same thing in India, Australia and New Zealand. One mind; four countries. What he did is extraordinary. I feel very lucky to have had a chance to hear him. I took so much strength from what he said because we are used to storytelling and changing the minds of people through storytelling. This was very much a part of me. And to see the magic of images was quite special.

One thing Christmas at Moose Factory does very effectively is to combine drawings with sound. It opens with the close-up of a black and brown dog, and then you hear the howl of a dog and the camera pulls out and you see the animal tied to a post.

I was doing the sound when I went to Moose Factory. I was taping the things the children were doing, the weather and the wind, almost 24 hours a day. I was always making sound. I told the children so many stories and played games with them until it was like I was one of them. That’s when I said, “Now it’s your turn. You have to tell me a story.” They were at ease because I’d been with them so much and this is why they talk the way they do. They were not intimidated by me. It was as if I was part of the family. I’d been telling them stories for three years. They were themselves and their voices are just beautiful. The children all spoke Cree; their dialect was very charming and English was their second language. I went back there when I was doing Trick or Treaty? in 2013 and this woman with white hair comes up to me and says, “Do you recognize me?” and I said, “No, I’m sorry.” So she comes to my ear and sings a song that I taught the children at that time. She was probably in her eighties. It was very touching.

Incident at Restigouche, 1984, dir. Alanis Obomsawin. Photo: archive from 1981 used in the film Incident at Restigouche (1984). Photographer unknown. © Journal l’Aviron de Campbellton. All rights reserved. Courtesy National Film Board of Canada.

You have a fine instinct for how sound works in film. Does that come out of your being a singer and a performer?

For me, the word is sacred. It’s sound. That’s what counts for me first. When I started making films, I was singing a lot and telling stories all the time to children. Every time I would make a film, I would interview people recording just sound to find out what the story was before coming there with the camera. That’s how I start making a film. Unless I have to do guerrilla filmmaking because it’s different if you have to film something as it’s happening. But to prepare for working with the community, I first go in alone and do sounds, always. I never regret it because a person doesn’t have to feel intimidated by a camera and wonder, What do I look like? Is my house in order? All that stuff. You’re just talking and you’re telling your story. Often people say to me, “Oh, Alanis, I never told this to anybody.” And their voice changes; sometimes it gets very sad or very happy. You have all the different sounds that people make because of their feelings and you don’t lose the incredible intensity and quality and feeling of the words.

I was struck by your use of sound, like the marching boots of the police at the beginning of Incident at Restigouche. It’s very threatening and effective. You have an instinct for how sound can actually drive narrative.

Definitely. The first time I went to Moose Factory, I had taken the sound of the winds in every situation. There is even air at the bottom of a door in a rundown building, so it would make some kind of wind. I would take the wind in every way I could think of. I would tape people walking on the snow from far away; I’d see them coming and I would record them until they passed in front of me and continued walking away. You could feel where the person was, and you would have the sound of the steps for a very long track. For me, sound is magic. And it’s sacred. In Moose Factory I was taping the kids when they are sliding and playing. I was so happy because when we put the film together, we had all this sound that was so spatial.

…to continue reading the interview with Alanis Obomsawin, order a copy of Issue #160 here, or Subscribe today.