“The Carnegie International”

The “Carnegie International,” established in 1896 by Andrew Carnegie for the purpose of collecting the “old masters of tomorrow,” is the second oldest show of international contemporary art in the world, having begun a year after the Venice Biennale. For the first time since its inception, there is a three person curatorial team, which includes Dan Byers, Tina Kukielski and Daniel Baumann. Thirty-five artists from 19 countries are featured in an exhibition that challenges the familiar format of the “International.” The curators have used this opportunity to explore their own institutional history as well as to engage with the local community.

Approaching the museum, you encounter a dense, forestlike installation that bisects the plaza and façade of the building. Colourful ribbons hang and wrap around the outstretched “branches” of Phyllida Barlow’s Tip, 2013. Nearby Lozziwurm, 1972, a usable play structure designed by Swiss artist Ivan Pestalozzi, hints at what will be discovered inside while also engaging the museum’s youngest visitors. The strangely affecting experience of entering the museum leads to an expectation of a highly immersive “International,” similar to Douglas Fogle’s 2008 “Life on Mars.” Instead, the curators have opted for works of a more intimate scale. The show is installed throughout the museum, including the unlikely settings of the café and coatroom, and even crosses into the Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

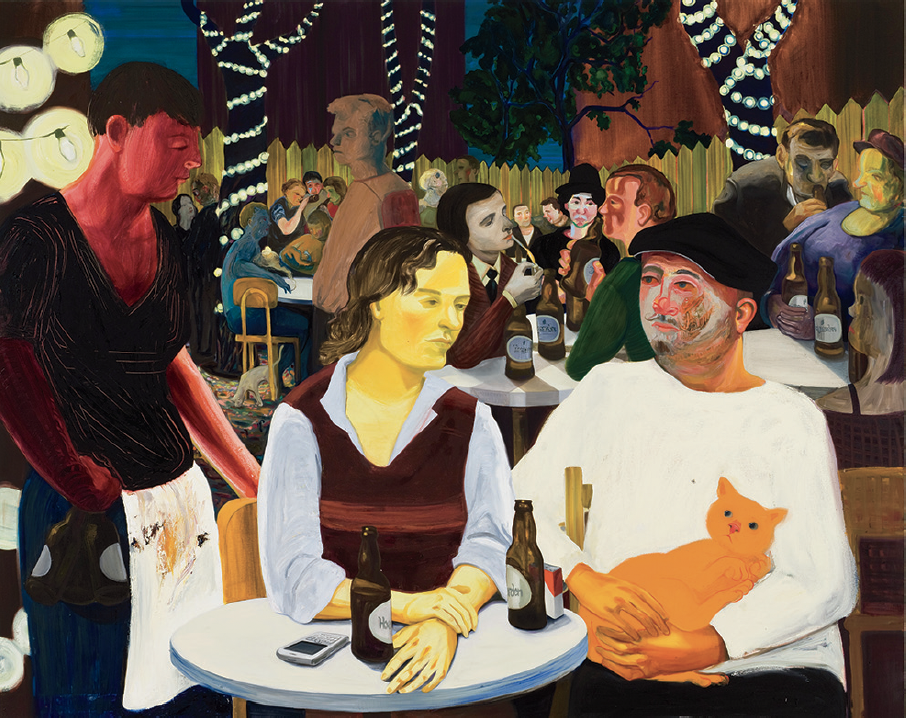

Nicole Eisenman, Beer Garden with Ulrike and Celeste, 2009, oil on canvas, 65 x 82 inches. Hall collection. Courtesy the artist and Koenig & Clinton, New York. Photographs: courtesy Carnegie Museum of Art.

The curators have pursued the laudable yet challenging goal of moving the exhibition beyond the museum walls to engage with the citizens of Pittsburgh. In early incarnations this endeavour was avoided to ensure the show lived up to its name and was not perceived as limited to the local. In the globalized contemporary context, this new effort reflects the broader re-evaluation of the significance of place. Engagement with the community has resulted in the artist collective Transformazium’s partnership with the Braddock Carnegie Library creating an Art Lending Collection. Artists, including the majority of those in the “International,” donated pieces to this program, which is intended to engage an audience who might otherwise not take part in the city’s art community. At the same time it also examined the value of art distinct from its monetary worth.

Local participation is a component of Zoe Strauss’s Homesteading, 2013, which involved the photographer’s setting up a temporary portrait studio in Homestead, Pennsylvania. This borough used to be home to one of the largest steel mills in the world, which in the 19th century had been key to Carnegie’s financial success. Since the closure of the Steel Works company in 1986 the population has dwindled, and there has been no meaningful replacement for the industry. Over a six-week period Strauss photographed people with connections to Homestead, and the resulting portraits and complementary video work form her contribution. This type of community project necessitates sensitive collaboration to ensure that the disenfranchised are not further exploited. However the small-scale portraits disconnected from individual names, in essence anonymous, convey an unequal relationship.

In the current “International,” galleries that usually provide a white cube context are transformed by an overwhelming installation that places the amorphous forms of Vincent Fecteau’s sculptures alongside a grid installation of Joseph Yoakum’s drawings and Pierre Leguillon’s pseudo-scientific A Vivarium for George E. Ohr, 2013. The curators’ installation establishes new dialogues among disparate artists and works, engaging audiences in ways that almost require an interactive experience. A second work by Leguillon might be missed since it is displayed in the Museum of Natural History’s Botany Hall. Those who make the trek beyond the limits of the art galleries will discover Jean Dubuffet Typographer (diorama), 2013, alongside flora dioramas. This setting highlights the artist’s interest in establishing new systems of classification and reveals unexpected connections among objects of different orders.

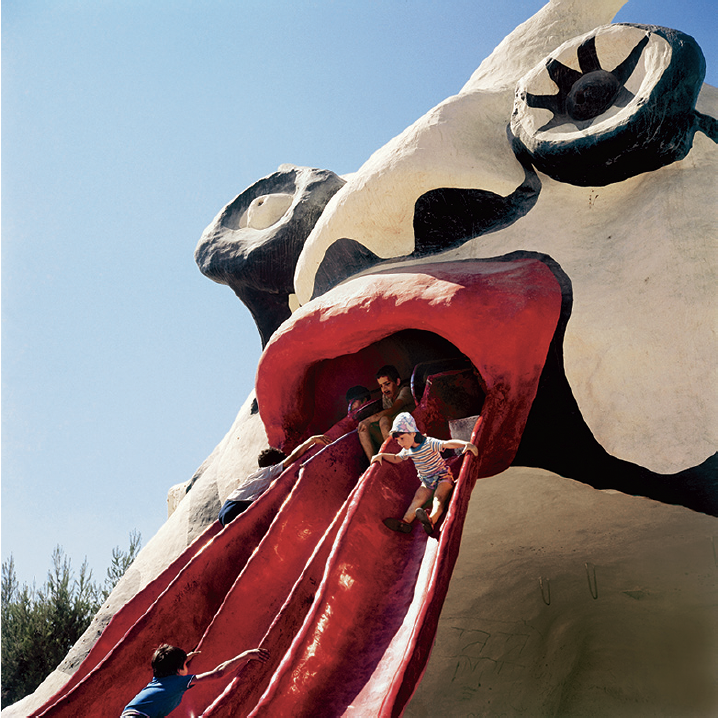

Niki de Saint Phalle, Golem (Mifletzet), Rabinovich Park, Jerusalem, 1972, metal and concrete construction, 354 x 551 x 630 inches. Collection City of Jerusalem.

The familiar and renowned Hall of Architecture, installed much the same way as it was more than 100 years ago, is transformed by Gabriel Sierra’s minimalist intervention, which has turned the previously moss green walls a vibrant purple. The addition of minimalist sculptures could be missed among the grand plaster casts that dominate the space. This work, particularly striking for people familiar with the space, creates an uncanny experience that further dislocates the simulacra of great architectural and sculptural monuments.

Likewise, the nearby Hall of Sculpture, a replica of the Parthenon’s interior, is entirely altered by the installations of Pedro Reyes and Nicole Eisenman. Reyes has continued his practice of transforming guns into “instruments of life”—in this instance self-playing musical instruments that intermittently perform concerts. The work of Eisenman, winner of the Carnegie Prize, is displayed around the upper balcony. The selection of 19 paintings form a mini retrospective that is complemented by her new exploration of sculpture: rough plaster figures that are a shocking juxtaposition to the perfection of classical figure casts.

For the first time, the exhibition includes a reinstallation of the modern and contemporary permanent galleries elucidating the development of the collection, which is inseparable from the “International.” This engagement with the exhibition’s history continues in the premodern galleries where there are identifying labels on all works that were purchased from “Internationals” since the show’s inception. Visitors can follow the development of the collection from the acquisition of Winslow Homer’s The Wreck, 1896, to works purchased this year, effectively positioning the current iteration within the institution’s history.

Zoe Strauss, Half House, Camden, NJ, 2008, colour archival inkjet print. AW Mellon Acquisition Fund. Courtesy the artist.

The Lozziwurm, encountered in front of the museum, is a component of “The Playground Project,” a unique exhibition within the “International.” It is displayed in the Heinz Architectural Center, a context appropriate for a show exploring the evolution of playground architecture in Europe, Japan and North America. A somber note is struck in the nearby video installation by Ei Arakawa and Henning Bohl. This sci-fi film follows a family-like unit as they travel throughout the now infamous Fukushima prefecture and visit the kindergartens and playgrounds, supposedly safe places for the innocent, designed by architect Mitsuru Senda.

Unquestionably a successful show, it is at times unwieldy due to the many disparate components. At the same time it is these innovative changes and additions that will be the lasting legacy of “Carnegie International 2013.” The curatorial team has transformed the exhibition as an institution through an examination of its history, and by forging new relationships with the citizens of Pittsburgh—endeavours that would likely meet with the approval of Andrew Carnegie himself. ❚

“2013 Carnegie International” was exhibited at the Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, from October 5, 2013 to March 16, 2014.

Krystina Mierins is a Toronto-based independent writer.