The Body’s Mystery and Journey

An Interview with Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans’s embrace of the idea that “if one thing matters, everything matters” easily leads to a practice where if one thing is worth photographing, everything is worth photographing. This aesthetic approach offers an exhilarating freedom. It has “allowed” him, a word he uses frequently in conversation, to take photographs of many things and to make photographs from strange things. His abstract images come about when he feeds paper through a developer that is contaminated with dirt and chemical traces of silver. The process results in an extraordinarily seductive series of camera-less images called “silvers,” which are resolutely material and imaginatively suggestive. Their abstract nature provokes our representational inclinations. We see them as worlds that are both wondrous and wounded.

Tillmans won the Turner Prize in 2000, the first photographer to do so, and with the prize money he purchased an industrial printer. Then in 2011 he made CLC 800, dismantled, a photograph of the now obsolete and deconstructed 10-year-old Canon copier. The machine that made images becomes an image itself. The photograph is an example of the flexibility with which Tillmans engages the world around him. His instinctive fluidity is now manifesting itself in the audio and video work (one aspect of this emerges in what he calls “audio photography”) that are now integral parts of his art production. In his “paper drops,” which he began in 2001, he treats the photograph as an object. Every single thing for him is a possible other thing; thinking about one medium puts him in mind of another medium.

Wolfgang Tillmans, wake, 2001. Images courtesy the artist; David Zwirner, New York/Hong Kong; Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne; Maureen Paley, London.

Wolfgang Tillmans, outside Planet, view, 1992.

In one way, taking and making images is only one step in a process of seeing that includes the art of installation. Installing his photographs is another critical meaning-making procedure. He understands that any one of his images, in whatever scale, changes when placed in a relationship with any other single, or any number of other images. Among contemporary photographers, no one is more effective than Wolfgang Tillmans in activating the space of the exhibition. His mind does not easily settle, and the resulting exhibitions have about them an air of reassuring and comfortable restlessness.

Wolfgang Tillmans’s first museum survey exhibition, “To look without fear,” opened on September 12, 2022, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, where it remains until January 1, 2023. From there it will travel to the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto (April 15 to September 20, 2023) and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (November 2023 to February 2024).

The following interview was conducted by phone to Germany in two parts, on Monday, July 25, and on Friday, July 29, 2022. Border Crossings would like to thank Julia Lukacher, the director of communications at the David Zwirner Gallery in New York; Stephanie Katsias, the senior publicist in the Department of Communications and Public Affairs at MoMA; and Alison Midgley from Studio Wolfgang Tillmans for their help in setting up and co-ordinating the interviews.

BORDER CROSSINGS: How many works are going to the show for MoMA?

WOLFGANG TILLMANS: In the end, there will be something like 350 across all the rooms, ranging from a postcard size to the largest print, which is eight metres by five metres. Even though the exhibition has been very carefully planned in design and model, I take more than I’ll need. The organization beforehand is only to make sure that I have a plan that allows me to respond to how the space actually feels and unfolds. All three spaces where the exhibition will be installed are, of course, very different. I conceived the system of the three sizes of my prints, which we call small, medium and large, and it’s a shorthand that I have consistently used since 1992. In their unframed versions they are incredibly lightweight and easy to move, which allows me to take more work than I can hang. Because of logistics and transport costs, it wouldn’t be right to take tons of heavy material with me, half of which I’ll not be able to use, so the flexibility is part of the concept.

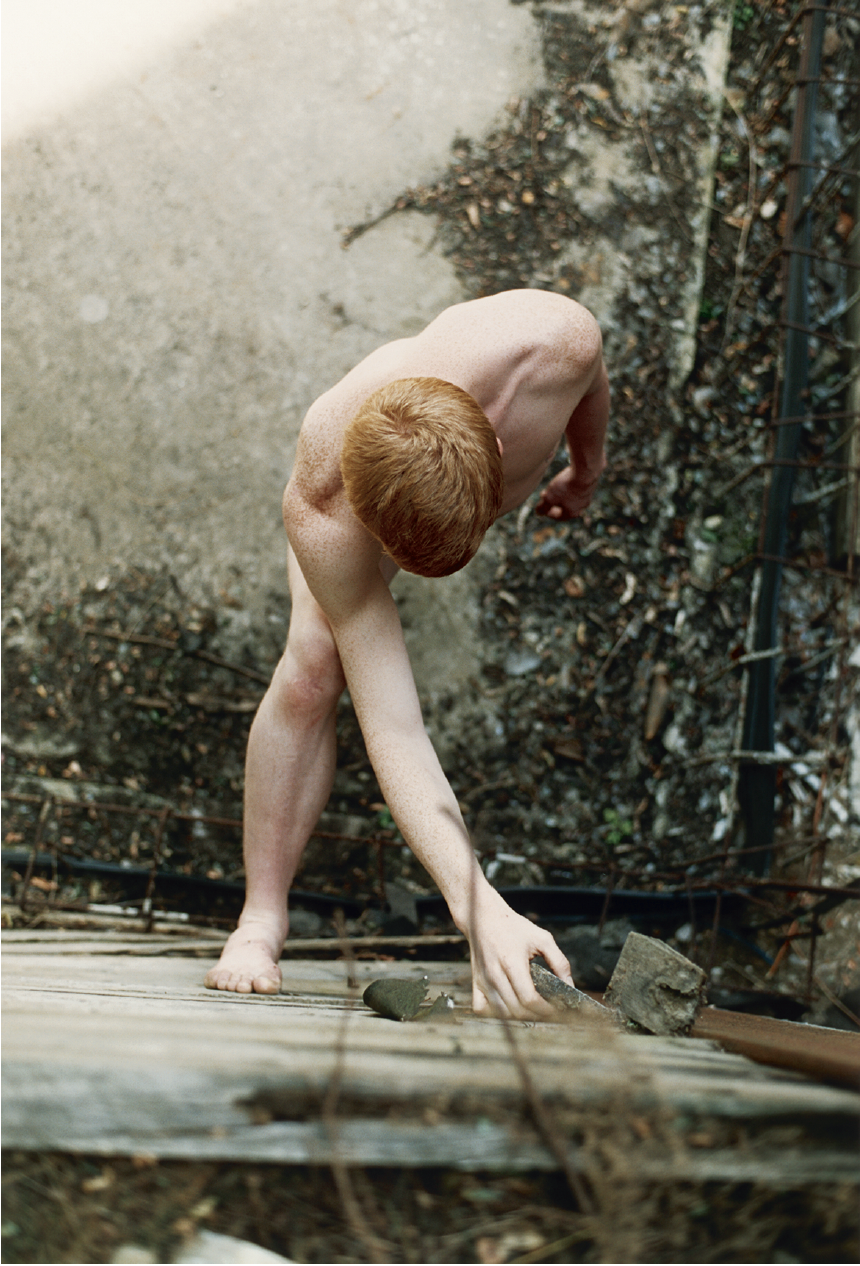

Wolfgang Tillmans, Dan, 2008.

Wolfgang Tillmans, Still life with Juan Pablo’s tree, 2021.

It seems as if you never really intended to be a photographer. I assumed you wanted to be an astronomer. Why did it take you so long to get to photography?

There were lucky coincidences at play in my youth. One was that I wasn’t artistically talented. I wasn’t the one in school who could draw particularly well, and I wasn’t recognized as particularly musical, so I didn’t have the pressure of being the artist in the family, or having to be the artist in school. Instead, I was developing my own value system, so to speak, between high art and pop art and pop music. I started to make my own language. The other thing that was fortunate in hindsight was that I come from a family of avid amateur photographers, going back to my great-grandmother. I never felt compelled to use photography as a medium to express my deviant teenage interest. That’s why it took me until I was 20 before I bought my first camera. A few photographs did emerge from when I was 17 and 18, and they have been exhibited and are considered part of my oeuvre.

You discover this Canon photocopier and you get entranced by what it can do, and it’s as if you buy a camera so you can feed the machine. You come at photography through a different technology.

I guess the printed page and ink and toner and anything that can be put on paper have always had a strong allure and attraction for me. The more you care about a graphic medium, the more you realize that it all is about how the ink, or whatever material it is, sits and connects to the base. Whether it’s a drawing, a photocopy or a photograph, it’s a carrier of image information. This is an intensely man-made process, even when it’s machine-made, and somehow, I’ve been sensually very aware of that. What that means is not so clear, but in music we would not question such attractions, like the electric guitar has an incredible texture and sound that has a value in itself. Just like electronic music synthesizes the very nature of its being strangely generated, and that is part of its attraction and meaning.

In the music video Make It Up As You Go Along (2016), the most attractive images are printing cylinders with ink rolling off them. There’s a sensual quality to looking at the machine as it works.

Yes. It’s impossible to know if people who grew up without any knowledge of technology would find these mechanical processes visually stimulating or meaningful, but I guess because we are surrounded by them, the technical workings of machines are part of our visual curiosity. I guess we are all familiar with the outside of cars, or we are familiar with books, but we don’t know what goes on inside a car or inside a printing press, and when you actually take a look, it has more poetry than you thought.

Your aesthetic is so profoundly non-hierarchical. How did it develop?

I developed that photographic language in those first three years after I bought the camera in ’88, ’89 and ’90. By the end of ’91, stylistically, I had found the lens language. I was fascinated by photographic styles in the 1980s like cross-processing, when you put a negative film through a slide process or the slide film through a negative processing machine. In the second half of the ’80s particularly, there were all sorts of effects—an extreme wide angle or extreme colours—that photographers were trying out on every story and on every portrait. Also, in terms of expressiveness, I felt that young people were often depicted making funny gestures, almost as if they were excusing themselves for being in this passing phase that is called “youth,” and I felt, no, I’m not in a passing phase. I’m who I am and I’m serious. I’m not just some fun consumer. I always took myself seriously, but I wanted to express this seriousness in a neutral visual language that, of course, was not neutral in the landscape in which it landed. It became very recognizable. I wanted to strip back to a clearly readable effect and to show things as they are. It’s too simple to say that I just wanted to show ordinary things as dignified. I also wanted to show extraordinary things as dignified but in a naturalistic way. I don’t want to ever bring things down. The mindset embedded in the zeitgeist of the early ’90s was a general, more sober rejection of ’80s glitz and glamour and a need to look at how things really are, knowing that there is no such thing as how things really are. The moment you depict them, it’s already an interpretation. So what I wanted to get at was personal and embedded in that time, but I also come from Germany and in particular from the Rhineland, where there has been a photographic tradition of August Sander and Bernd and Hilla Becher, and the Neue Sachlichkeit art movement of the 1920s. But there wouldn’t be Neue Sachlichkeit without naturalism and Gustave Courbet, so when you look back there always have been artists who wanted to cross hierarchies. In the late ’90s I looked at Caravaggio paintings wherever I could find them; his painting the dirty feet of saints is such a non-hierarchical gesture.

Wolfgang Tillmans, young woman, Chemistry, 1992. Image courtesy the artist; David Zwirner, New York/Hong Kong; Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne; Maureen Paley, London.

You have that beautiful photograph of a flower with five small reproductions of Caravaggio paintings sitting in what looks like an industrial window.

That was exactly from the time when I looked at him.

What Sander wanted was to document an entire culture and the Bechers were equally ambitious in assembling their typologies of industrial structures. Was your aspiration when you started out, and subsequently, to encompass that larger vision or was it something more modest that focused on intimate and restrained details?

As it stands now, the project is in its fourth decade and is anything but intimate. It’s sprawling and all-encompassing, including the fold of a T-shirt, the aesthetics of what astronomers see through the biggest telescope on Earth and the surface of the visible world. It all somehow became a part of what I was doing. If I had started all that at the same time, it probably would have been an unmanageable project, but because I work in elliptical, circular ways, I end up coming back to similar subject matter 10 years later. It all accumulates in an attempt to make a picture of what it feels like to live today. I guess it’s not more modest in outcome.

When you say that, my mind goes to the great American poet Walt Whitman. In the 24th poem of his “Song of Myself,” he goes from his sense of being what he calls “a kosmos, / Turbulent, fleshy, sensual,” to the minutiae of “beetles rolling balls of dung.” The scale of your work also moves from the cosmos to the quotidian.

Yes. When I lived in New York in the mid-’90s, I was aware of Whitman and I can see those points of connection.

I’m going to mention another poet as a way of making a connection between space, perception and sexual politics. In one of your talks, you refer to the optical properties of the eye and point out that the cornea is good for colour perception but not good for light perception. So when you’re looking through a telescope, you have to look from the side to see distant planets and solar systems. You’ve also said that in German, “queer” means “from an angle.” So as a gay man, you have to come at things from the side. I realized that you were queering astronomy.

I haven’t thought of it in that sense, but I’m always open to new readings. I have to admit I always thought there was something sexy in the nerdiness of astronomers.

Wolfgang Tillmans, Lutz & Alex sitting in the trees, 1992. Images courtesy the artist; David Zwirner, New York/Hong Kong; Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne; Maureen Paley, London.

Wolfgang Tillmans, Alex & Lutz holding each other, 1992.

It made me think of Emily Dickinson, another 19th-century American poet, who operates in an entirely different spatial register from Whitman. In poem number 1263, she writes, “tell all the truth but tell it slant, / Success in circuit lies,” and at the end of the poem, she concludes, “The truth must dazzle gradually,” but that idea of seeing things slant is also the way you’ve suggested that, as a queer man, you had to come to the world. You couldn’t confront it directly because it was a hostile world.

I like the quote as well as the idea.

When you were documenting club culture in the late ’80s, you weren’t there as a chronicler but as an individual experiencing it. I assume you didn’t go there to take pictures; you went there to be in the space and the pictures evolved out of that presence.

Yes. In the beginning I wanted to tell i-D about how excellent the scene was in Hamburg, and out of that came a larger desire to communicate what I felt was a genuinely liberating and progressive togetherness. In the early days of ecstasy culture, it really seemed if everybody would have that experience, the world would be a more peaceful place. It probably sounds super-naïve, but, to be honest, I still believe in this peaceful power of ecstasy and the dance experience.

You’ve described the club scene as “an experimental chamber for human interaction,” but you also said it was a utopian ideal of togetherness. In every way, socially and sexually, it seems to have been a significant time for you.

Yes. But I use the term “club culture” as if it is one thing, but it is so many things, and the particularities of what I experienced or what the world experienced in the late ’80s and early ’90s were this very egalitarian version of nightlife. It was not all about club membership and what you wear. It is 30 years ago, and I can’t say that nightlife today is exactly the same as it was then. What was liberating for me might be intimidating for somebody in 2022 and it may not be so egalitarian. I was in Toronto in 2016 and after the talk, two 18- or 19-year-olds came up and asked, “How does one do a rave?” and when I inquired about their experience of nightlife, I realized that the whole idea of a party in an empty, unused warehouse didn’t exist for them. Most city centres just don’t have any unused empty space. I guess it’s all part of a bigger consideration now and many things play into it.

Do you look back on house culture with some sense of nostalgia because it was so special and vibrant and inspirational?

I do. Things were less commercialized and the world has become more economized. But good things have happened in the last 30 years and I’m not part of the doomsters. A lot of equality has been achieved only in the last 10 years, so why be nostalgic about a time when, for example, gay marriage was not even in the cards in the ’90s? It’s just a very different time.

Your intention wasn’t to be a documentarian, but now you realize that you did capture a sense of the time that is important for us to know about.

Yes. I never saw myself as a chronicler, but that had to do with being young and not wanting to do that. But I saw it from the inside and I see that those editorial projects were journalistic in essence. So while I’m not referred to as a photojournalist, I’m actually proud of having done some meaningful documentary work.

Were the first photographs you sent to i-D magazine the Lutz and Alex pictures?

No. That was in 1992. First, it was simply reportage on the nightlife from Hamburg. When I lived in England, I didn’t want to do any editorial work as a student, but at the end of my studies I reached out to i-D again, and then I did this reportage on techno in Europe. Its title, Techno is the sound of Europe, beautifully expressed the positive postwar European vibe of unity. After that, I contributed on a monthly basis in 1992, and the Alex and Lutz photographs appeared then. Even though I conceived, styled and photographed them, I could not have done so without Alex and Lutz’s collaborative input. They were so unusual that the magazine put “a fashion story” under the title “like brother, like sister.”

Wolfgang Tillmans, Kate sitting, 1996.

Wolfgang Tillmans, Kate with broccoli, 1996.

You never seemed to be interested in being a fashion photographer in any conventional sense.

The reason I’m hesitant to give a casual answer is because it might sound like I’m suggesting that fashion photography is something bad when it is a field of great expertise and craft and energy and excitement and something from which I’ve drawn a lot of inspiration. The definition of fashion photography is so varied. On the one hand, I’ve always been interested in clothes and the meaning of clothing, and, on the other hand, the particularities of fashion industry photography were never something that I was any good at, or had any interest in. But my work has been very influential on fashion photography, it has also been published alongside fashion photography and I have always looked at fashion and clothes. So I can’t say that I’ve had nothing to do with it because I have had a specific and unique position towards it.

I think of your work as being innocent. It starts in those early photographs of Lutz and Alex, and what seems to run through it is an openness to possibility. That quality strikes me at its core as being generous and innocent.

Innocent? The thing is, you cannot claim that yourself. The moment you do, it’s not innocent, so I find it hard to wholeheartedly say yes to this. It’s something others have to say. But what I could say is that I have an openness for the outcome. Many people look only for the outcome they want, which is natural, but I think the biggest challenge is to accept evidence that is different from what we expect. It’s similar when you make art. One has to make peace with the outcomes that one gets. I try to control as much as I can and I’m careful to know when to stop and when to accept the outcome that I get.

Wolfgang Tillmans, Venus transit, 2004. Image courtesy the artist; David Zwirner, New York/Hong Kong; Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne; Maureen Paley, London.

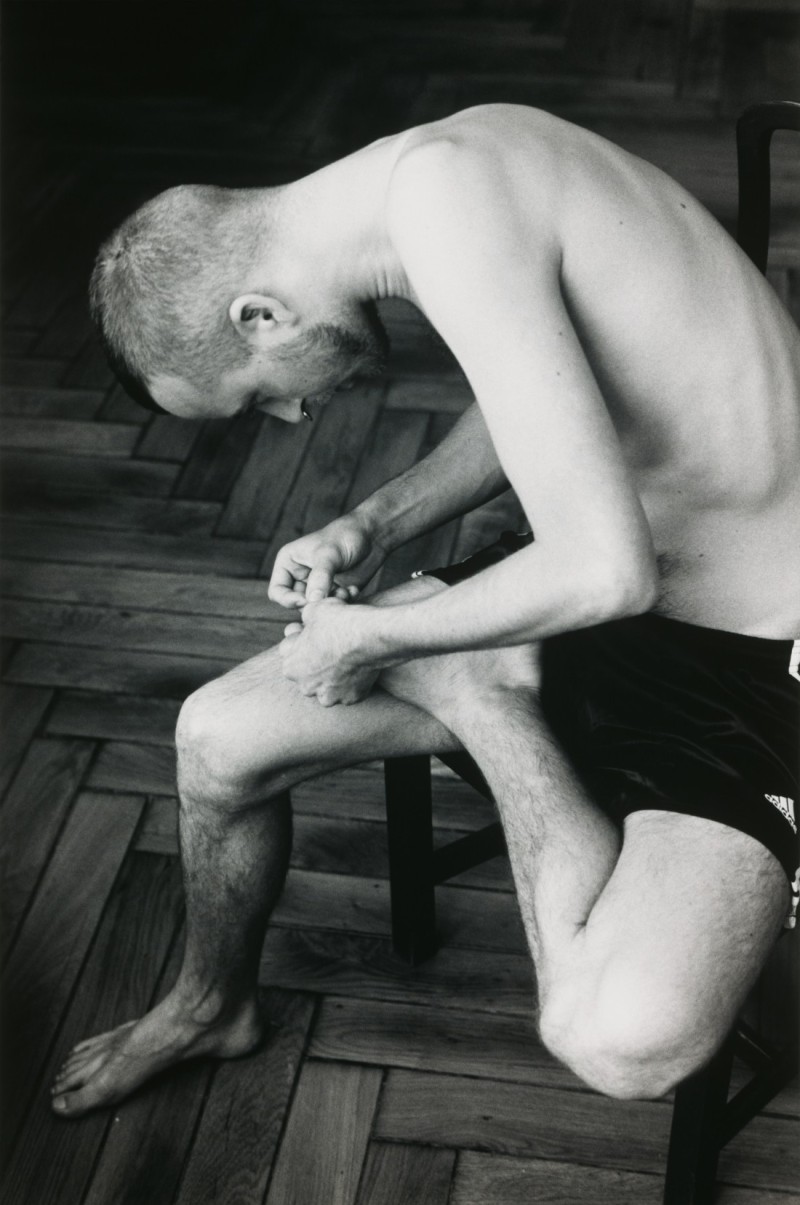

Wolfgang Tillmans, Anders pulling splinter from his foot, 2004. Image courtesy the artist; David Zwirner, New York/Hong Kong; Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne; Maureen Paley, London.

A photograph like astro crusto, a (2012) could be read as a memento mori, a reminder of death, but its brightness and cheeriness resist that reading. It actually becomes a very positive image. I assume that’s a conscious choice you make about what it is your lens captures.

Yes. The memento mori “thing” is potentially in so many things, like the temporalness of life and of any given moment. A strong presence and a connectedness to that has been very clear to me from an early age. I’m happy that I have made peace with the full tragedy of life because it’s absolutely unavoidable and quite overwhelming. I turned 54 this summer, and my parents are starting to get very frail, some friends are dying from diseases and there are freak accidents. Basically, death is all around us.

I look at the “Urgency” series and I see the surface as thin blood. The read for me is wound more than wonder. Are you okay with that reading of such a beautiful work?

If it is readable only as that, then I wouldn’t have done them. In my art I’ve always claimed freedom and liberty in being allowed to make something that looks red and fibrey and liquidy and still not see blood in it. I’m allowed to photograph a sunset and not see a cliché in it. I try to see innocent inquiry and that allowed me to turn some stones that others might not have even bothered turning. If I had been afraid of the “Urgencies” being only about blood, it might have stopped me from doing them. I never saw them as bloody, even though, of course, it’s bloody obvious to do so.

But it’s so subtle. It’s like the bleed of the red from the centre of a turntable into very black water in one of your music videos. The black water picks up the suffusion of the red tones.

I was wondering what video I have that includes turntables. You know what it is? It’s a cooker, an electric stove, and the red is the fast-boiling plate. It’s fascinating that you read them as turntables.

My misreading came out of their shape and your interest in music. But what caught my eye was the subtle shift of one colour into another. That bleed seems to be very carefully calibrated.

Yes, that is true. Don’t use this as a headline, but it’s all about colour. We can’t always say what colour means, but the fact is, most of us see colour all our lives. We are constantly evaluating it, like what colours appear at what time of day? What are their light sources? Not equally, but we are all subconsciously and subtly well-versed in reading colour. I’m like a super-colour reader, so I cannot have it as a central consideration in everything that I compose and bring together.

The range of your palette is extensive. In the lens-based photographs from Fruit Logistica, there is an extravagance of colour that is almost overwhelming. In the camera-less work in the “Lighter” and “Silver” series, you move from multicoloured surfaces to monochromatic ones.

With “Lighter,” because there is no lens, the image is made with light. And the folding and shaping of the paper in the darkroom influences the angles at which the light shines on them, so they are really a depiction of their sculptural form. I choose the colours through a trial-and-error mixing of different light sources of different colours—a red, green, blue or yellow. It’s not so much a depiction of colour, as almost a making of colour in the first degree.

Wolfgang Tillmans, installation view, “Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear.” Courtesy the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Emile Askey.

Wolfgang Tillmans, Freischwimmer, 2003.

Your work makes me look closely at things. A piece like Blushes #26, a tiny shape on a large surface, is an image that gets away with as little as it can. Then in Lighter, white III and IV, there’s even less to see. The surface is only tone. Do you read these two works as different gradations of minimalism?

They’re distinctly different languages that I usually don’t fit so near to each other on a wall. The “Silvers” also don’t necessarily hang right next to the “Freischwimmers,” even though at MoMA they are sometimes inhabiting the same space. But they’re not the same colour/space explorations, and I don’t upkeep endless amounts of these fields. It’s not that I invent two new ones every year. For example, the invention of the “Blushes” and “Freischwimmers” happened in 2000 and has been fuelling my interest ever since. I started to collect and create the “Silvers” from ’92; I named them only in 1998 and it’s been one ongoing exploration. I’m constantly experimenting, always trying out things and playing with my eye, playing with the camera, playing with paper, with a photocopier. In the end there are sometimes striking results that I choose not to pursue because they would add too much confusion. It allows me to hang 30 years of work in one exhibition, often side by side. They couldn’t be more different, and it’s unusual for works that were made 25 years apart to somehow hang together. But it’s only one result of carefully choosing what not to show, which probably goes for everybody. Half the work is deciding what not to show, what not to do, what project not to go down. Visually, there are a ton of great effects and things one could do. Initially, I always mistrust every picture, every photograph. Like, are you just trying to please me? For example, I almost deliberately overlooked the Tukan (2010). To filter out pictures that are too loud is superimportant, and then there are some loud ones that are really, really good.

Wolfgang Tillmans, o.M., 1997. Images courtesy the artist; David Zwirner, New York/Hong Kong; Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne; Maureen Paley, London.

Your work never has a Best Before date. It’s always good all the time.

Obviously, that’s something I couldn’t have planned. You can’t plan to stay relevant. It’s a humble hope that you can have. But I’ve never been afraid of being of my time. I recognize that other artists fear being too much of their time, but the fear of becoming passive is not a reliable way of that not happening to your work.

When you say “somehow Jurys Inn [2010] becomes a good picture,” you’re being slightly disingenuous. It becomes a good picture because of the way you frame it and pick up the colour harmonies of orange and tan in the details of the furniture and decoration. It turns into a good picture because you make it one.

I guess what I may amend is how unlikely it is that that room could make a good picture. Actually, it’s so bad, it made it even into the MoMA show.

Let me concentrate on something that is important to you: the body. The title of your recent exhibition in Budapest is “Your body is yours,” and your interest in the body is especially evident in Life Guarding (2020), a sensual video that moves from an almost classical collage of male bodies to edible things—eggplants and cucumbers and corn—that are all phallic. Were you pushing the notion of body as much as I’m reading it?

To be honest, I never see the phallic-ness of things in nature. No, that’s not true. In the market when I pick up some courgettes, their size and feel make me think what they could be. We can talk about flesh with fruit because what makes it so appealing are its fleshy forms. But the body is the single biggest mystery we have and it’s the vessel of our journey. I recently titled a couple of pictures The Body is the Journey, which 20 years ago I would have thought was too charged, or even too kitsch. But it really is. When I say the body is all we have, and the body is the mystery and the body is the journey, it may be amateur philosophy, but that doesn’t make the feeling that I have about it any less intense.

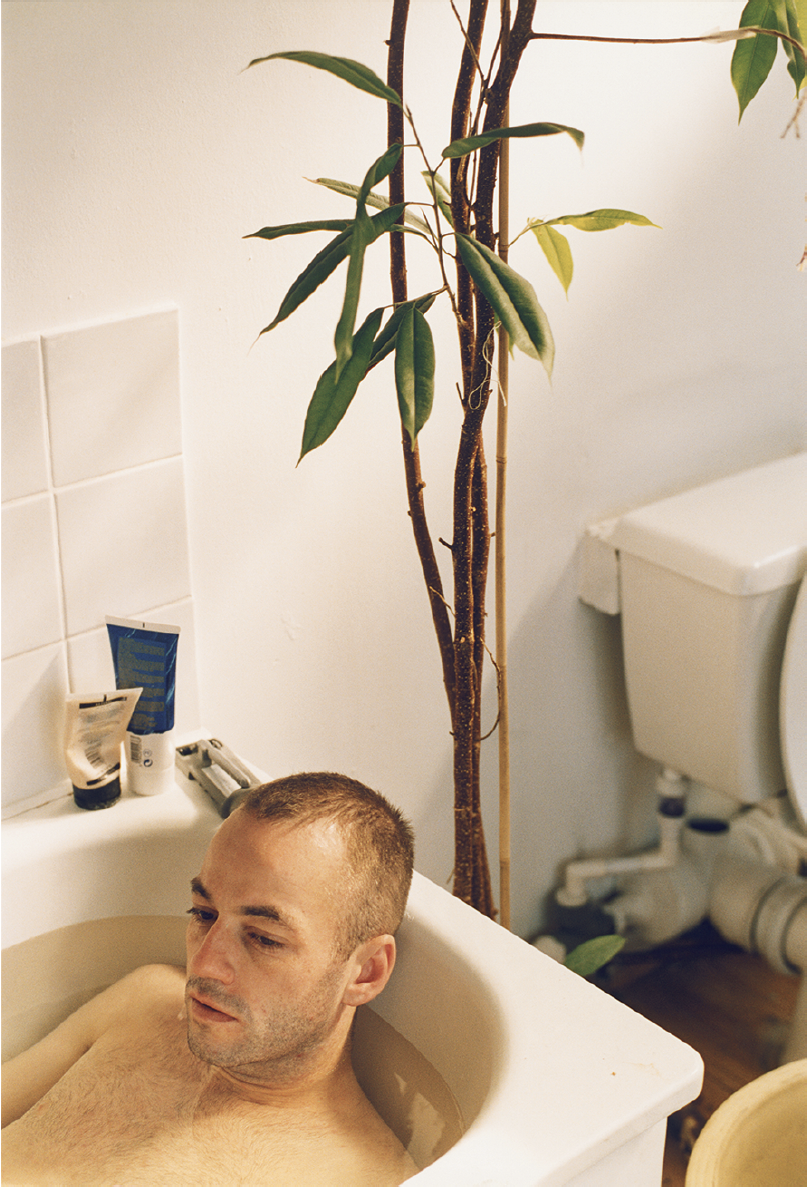

Wolfgang Tillmans, Jochen taking a bath, 1997.

The physicality of your work cuts across genders and desires. In the Trafó Gallery exhibition in Budapest, you included a club image called young woman, Chemistry (1992) of an attractive woman who has a thin line of perspiration running down her chest between her breasts. What is it about that image that you find so appealing?

I guess it’s this quintessential, sweaty club feeling of heightened body awareness that comes with ecstasy and community. It doesn’t all depend on ecstasy, but it is what connected at the time.

Do you distinguish between the way you appear in photography as opposed to how you present yourself in the music videos? In Fragile, the 27-minute-long visual album you released in 2016, you appear with Hari Nef and Ash B.

True. Around 2014 I took a self-declared sabbatical, which doesn’t mean that I did nothing. It was a very active year in which I had time to focus on a more performative side of myself. I had been making music and singing, and paused for 30 years and then I made a video called Instrument in 2014, a gallery piece where I’m in underwear, hopping from one leg to the other, which makes the rhythm I recorded. I play with the rhythm and with the sound and I become my own instrument. That was the first video I was actively in. Wanting to manipulate the sound of the stepping noises was really where I touched base again with making music. Things started from there, so to understand the lectures and the talks as a performative activity, I realized that either I have a very captive audience, or I do something that keeps an audience together for 80 minutes. I noticed again and again that these talks are freestyle talking over pictures, and in Toronto, Vancouver and in many cities, they draw several hundreds of visitors. The last thing is my interest in words and language, which I may have lived out in titles of single works and exhibition titles, but I’ve been more deliberate in bringing them all together, and that’s where I also stepped in front of the camera more.

Wolfgang Tillmans, The Cock (kiss), 2002.

Music seems central to so much of what you do, and it even plays into your installations. You think individual photographs have a tone or an individual sound, don’t you?

And colour is sound or tone and an installation in the exhibition space has a resonance. Each exhibition space has a resonance, and the colours that are put into it ricochet and sparkle or wink, but together they are something that I like in musical terms, like rhythm. Now that I think of it, it’s not such a surprise because we are looking at gallery walls usually in one direction. One goes from one side to another and then the next wall and the next wall, so it is a score. It’s a sequence—that’s the word. Nowadays, all the multi-tracks on a computer screen are laid out on a timeline and how they come in and out, switch in and out, is visually very striking. But it’s really a side thought. When I’m in my pictures, the main thing is it’s 100% visual.

In a conversation in 2020, you talked about the transformative magic and mystery of photography. Is it still that kind of process?

When it happens, it is. But then it is also in music and probably in all art. When things come together in a way that is larger than what you plan or intend, you have the humility to allow them to happen. The most important thing is to recognize things when they happen and to be open to that. For example, Lüneburg (self) is a 2020 self-portrait where I am in an iPhone that is leaning against the water bottle. Against all odds, I took a big SLR to this hospital where I had metal taken out after a knee injury, and I saw these strange bodies of glass, the water bottle, this transparent silicone wrapper and the glass screen, which was a window into my boyfriend’s bedroom, and I made this mini-sculpture. I see it, I know I did it, but now I am a third-party viewer and I’m just grateful that it happened. Every day millions of people make these mini-sculptures where they lean their phone against something for a video call. I can explain it all and at the same time I humbly recognize how unlikely it is to make a good picture of a smart phone.

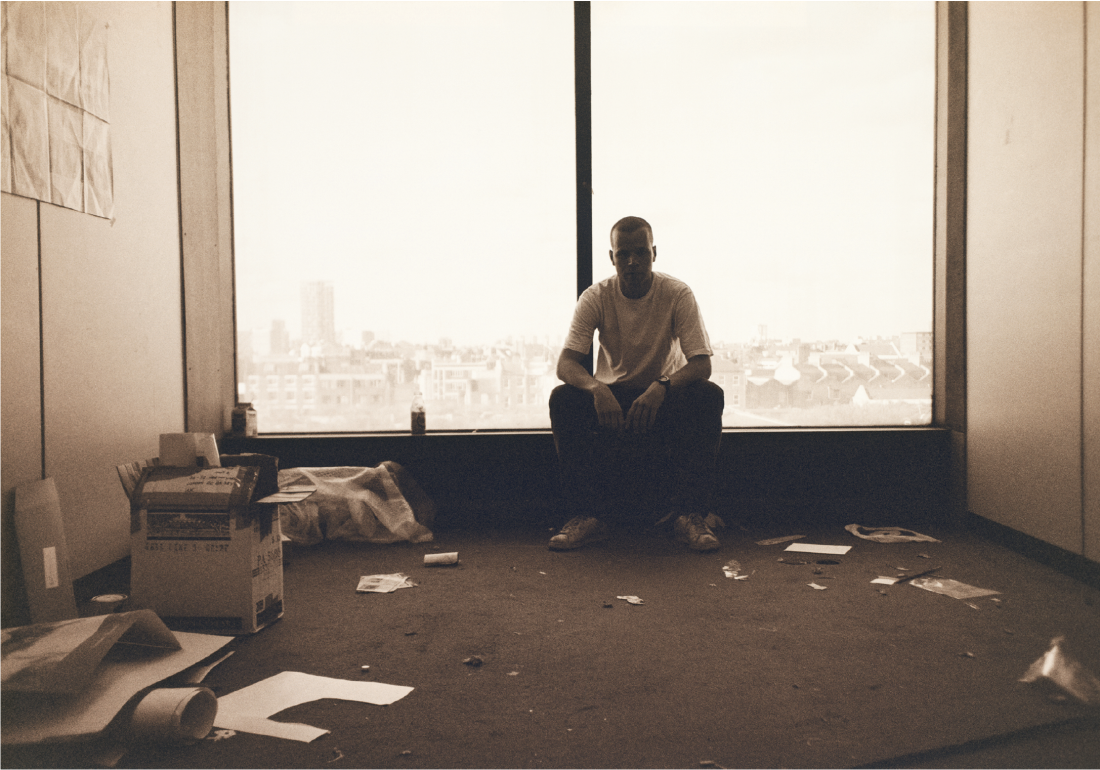

Wolfgang Tillmans, I don’t want to get over you, 2000. Images courtesy the artist; David Zwirner, New York/Hong Kong; Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne; Maureen Paley, London.

What is it about borders that interests you so much?

Because they determine so much in people’s lives. When it is not so clear what logic they were drawn by, or exist by, there is an arbitrariness that is intriguing. We can talk about borders as a change from one thing to another. In my spectrum, for example, I consider the line where water becomes a frozen border, or the line where water hits the horizon. Then there are physical borders between countries. I’ve never made work that tries to explain them in particular; it’s more about acknowledging how important they are and that they’re often irrational, especially between countries. So many borders have been drawn up without considering what the people who lived there thought about them. The border between what is visible and invisible is also a huge fascination. There is a border in space between what we can see and what we can’t see; or the notion of clothing being the membrane between the inner self and the outside. The outside of a building is a border. Can we read the inside through reading the outside?

The border is very fertile territory because it gives you so many possibilities of reading and rereading the world. The underlying theme of your entire exhibition in Porto was states of matter moving between gas and liquid and solid.

What I find intriguing in this interview with you, someone who has studied and looked very closely and well at the work and my strategies, is that rather than saying, “Yes, you’re right,” I feel encouraged to question all of this, or to at least question what is its relevance? What does it mean? I would say, this heightening awareness for how something feels is really my goal. That exhibition in Porto was at that point before the wave of Brexit and Trump crashed into land. The largest picture in the show was this dark seascape called The State We’re In, which showed the surface of the Atlantic Ocean bristling with energy, seeming as if it was about to erupt. None of it has stopped these political developments from happening. But that alone can never be the measure of art or to demand that of art. Judging art by its effectiveness in changing politics is asking too much.

Wolfgang Tillmans, hanging tulip, 2020.

During our previous conversation four days ago and again today, you have raised this question of epistemological doubt. You keep asking, “What does it mean?” From a viewer’s point of view, I would say your work is profoundly meaningful, but do I have more confidence in it than you do? I understand the humility, but I don’t quite know what to do about this constant questioning of whether you put meaning on the page.

In the last four weeks or so, I’ve been in a number of interview situations, and I can’t help but try to keep it an active engagement with my real thoughts rather than to wheel off premeditated thoughts. I have tried to use these interviews as moments to reflect, and I can’t bring myself to say, “You’re right, my pictures are really meaningful.” Maybe I should be more chill and say, “Yes, The State We’re In is an incredible history picture; it captured and expressed in its title something that thousands of people who saw it could really feel.” But what good is that for me to say? It’s not that I’m putting on an artificial humility, either. I mean, it’s real. Also, it might have meaning now, but you don’t know whether that will be retained over time. I find it interesting that the reading of works of art changes over time.

When I interviewed Nan Goldin last year, I remarked that her extraordinary work has made her part of the history of photography. Her response was to say I was being generous, but she didn’t share my certainty about her place. She has the same doubt about history that you’re expressing.

Maybe it is not right to put artists on the spot. I can say with certainty that Nan has made an indelible contribution to the history of picture-making. If you take the history of pictures of humans, Nan Goldin has a page in that. But why would she formulate it like that? You can humbly say yes, or there are master macho ego artists who talk about their own grandeur and importance in their lifetime. But it’s totally uninteresting, or at least totally unattractive. I don’t want to be around that person. I don’t want to hear it from him.

Wolfgang Tillmans, Zero Gravity III, 2001. Images courtesy the artist; David Zwirner, New York/Hong Kong; Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne; Maureen Paley, London.

Wolfgang Tillmans, it’s only love give it away, 2005.

One of the things that have characterized your work is a notion of fragility and vulnerability. I think of Nan Goldin in the same context. Why are those qualities so important in your work? Do they emerge because they are part of the human condition or are they something you actively seek out and then find ways to locate in your photographs?

What I pick up on is not something I deliberately seek out. It was more something that stuck with me and that felt like the central point on the path of finding my language, a language that admits doubt while aiming for a maximum of control, of mastering my art whilst questioning it and questioning my assumptions of knowledge. This goes back to me observing that some people, friends, other artists and politicians, seem super-sure of themselves. Maybe not. Maybe that’s also why I had such a problem being misunderstood as part of advertising and fashion photography in the 1990s. Fashion photography is all about projecting success and projecting control. The deliberate projection of a low-life, grungy aesthetic for the purpose of high-fashion marketing is highly self-assured and allows no room for doubt. It’s the total opposite of the DNA of my work. This doesn’t stop it from lying on tables in commercial production meetings and being used in mood boards for projects I know nothing about. I think if these probing questions seem a little uncomfortable, it has to do with the medium that I use, which is a very powerful, persuasive and eloquent one. It is being used as the main commercial opinion-making and style-making language of our time. To maintain this sense of openness and fragility over the years within a high-visibility world and context has been a lot of work and careful positioning and saying no to a lot of things.

I understand entirely this tension between the desire to control the result and the simultaneous admission that you’re not completely in control. But your purpose in whatever control you can exercise is to come away with what you call an “interesting image.” It raises a simple question for me: Do you always know that you have an interesting image?

I hope so. The thing is there’s so much hope in photography, which made the transfer to digital so difficult. Also, the psychology with film before digital was a triangle between the subject matter, the photographer and the result, which would come in a couple of days when you’ve seen the film. So there was a hope that you store in the photograph what you caught in the last minute, or five minutes ago. With digital photography, you look at the back of your camera and immediately see what is there. It took me a couple of years to unlearn looking at the screen as a tool to judge the quality of the work of the picture, and regard it only as a technical control panel to check an exposure, or if a camera shake or blur had occurred. Yes, sometimes I do feel it’s pretty much there in the moment; at other times, it takes some years for the picture to reveal itself.

Wolfgang Tillmans, paper drop (star), 2006. Images courtesy the artist; David Zwirner, New York/Hong Kong; Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne; Maureen Paley, London.

You’ve also said that you learned the language of photography by degrading photographs. I thought of Shakespeare’s The Tempest, where Caliban complains to Prospero, “You taught me language and my profit on it is I know how to curse.” In the language of photography, I have a sense that your preference is for the degraded cursing language of Caliban, rather than for Ariel’s clear clean-speaking.

I think the way you explain it, I would agree.

An image like Shooting Cloud Fucked Up Chemicals (1999) seems a perfect embodiment of this tension of control and randomness. The Parkett Edition (1992–98), where you retrieve a collection of fuck-ups, operates in the same way.

Yes. That was a very important work, which since has been dispersed in 60 places and collections. It contains a lot of the seed and the roots of what the work is really looking for in this ever-shifting junction of what the camera sends, what the film records and what ends up on the paper. Reality is when you get down to really putting it to paper with chemicals in the darkroom and light and all the shifting parameters of what can go wrong in that process. You can overdo the process; you can give all the colour in one direction, or you can oversaturate the paper. The full spectrum of what is possible includes all the things you can wilfully do wrong or right.

In the process of feeding undeveloped paper through what is a dirty photo-developing machine, you get these gorgeous chemical traces. Is that an example of beauty emerging accidentally? Do you have much control over what the “Silvers” end up looking like?

I do to the extent of how long I let the processing machine “ripen,” which means collecting dirt and the residue of the silver photochemical process. Otherwise, the marking of the surface is more dependent on the rollers and the mechanics of the machine. It’s more a question of time: when to do them and at what temperature. Then the only bit of control is the colour, if there is any colour, and if the lights are dark or the lights are on in the room before feeding the paper through the machine. Because when a fully exposed picture is fed through the machine in a room with the light switched on and with fresh chemicals, it results in a black print. If there’s just the slightest bit of photochemical activity in the tank, it might result in the cream colour or in all the different variations of colour and hue that are in the “Silver” work. It’s something I’ve been doing for 20-plus years. I never write down recipes, nor do I do that with the “Freischwimmer” or “Greifbar” series. I build the colours afresh every time. Obviously, I have a memory of what I did in a previous session four months ago or eight months ago. But there is always a deliberate, new starting point to arrive at a new colour spectrum.

Wolfgang Tillmans, La Palma, 2014. Images courtesy the artist; David Zwirner, New York/Hong Kong; Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne; Maureen Paley, London.

Wolfgang Tillmans, Animalistique, 2017.

Do you distinguish between abstract and representational photographs? Are they different kinds of work for you?

They are different and at the same time, they all deal with photography as some kind of evidence of there having been light and/or processing agents. Like a computer that can read the effect of the light onto the centre, or some chemicals that can read the effect on film or paper. What connects them is that they all are tied together with that sense of evidence. Philosophically I have them on the same foundation and maybe that is why they speak together in an exhibition, even though I don’t necessarily have them side by side. Sometimes I do. For example, I have put the high-definition new digital photographs next to the large-scale “Silvers,” which I call “abstractions” for the sake of language, even though they are what one would have called “concrete art.” The process depicts itself in a way. It’s fascinating what photography allowed me to do in collaboration with the viewer’s eyes and mind. Works like the “Freischwimmers” and the “Urgencies” would not have the same potency if I had painted them on canvas. Because the only reference would be, “Oh, he put that paint there. He put that mark there. This looks like a tear or a stain or a hurting. He put that there with his hand and with a brush.” But because their appearance is photographic, the brain connects them to evidence of a depiction of reality. Something that is essentially painterly in language is connected in the brain to something in the physical world, of the ethereal underwater, of inside the body, of the skin. That whole expansion of my language is something that I was super-happy to have found and been able to use.

Wolfgang Tillmans, Lüneburg (self), 2020.

I look at a photograph like Blushes #10 and I think of a meteor shower. It immediately connects me to a cosmological perception rather than just looking at things that end up being made on a piece of paper.

Absolutely. That is intentional. But I didn’t seek it out as a huge dossier where I drew up beforehand what I wanted to achieve. It’s that the research and exploration and study into the material and the pictorial potential are what I was doing those years and I didn’t stop. I saw the potential and connected the dots. That’s what made them happen and what allows you to see that meteor shower.

Can’t Escape into Space is this amazing video you made on Fire Island in an empty club just before closing time. It raises the question of intention and how meaning gets made. I know you filmed it in 2018 and wrote the lyrics in 2020. It’s about change and space. So what do I see? I see a disco ball and radiating colours moving in space, and, suddenly, the disco ball and a series of other circulating forms remind me of a solar system. I’m literally out in space. Then at the end you make a risky move; you return to the pool table where you have placed the cue ball and a single red ball on the surface. Of course, I immediately think you’re still playing with the cosmic idea and they are two planets. I read the video through the trope of space exploration.

Yes, it is. Everything is so there in the world; I don’t have to artfully arrange them. I often only have to pick them up and connect the dots. Here you have me in a more confident mode. I’m not searching to build this all up from scratch at the same time and, of course, sometimes I am elaborately staging things. The beauty was I was looking at them as balls in outer space and the incredible thing is that it’s possible to make them look like that. By just thinking something, when looking at something, I am able to imbue the result with that note. I’m very happy when the work lands with you in the way that it did. I’m cautious because I can’t be sure it will happen again. When I really feel it, it is very much there, but in the next moment you can be greedy and you want to feel it, but, unfortunately, only the one thing is there. When I really feel it, then, yes, the pool table can become a solar system, and the folds of a T-shirt can become something much larger and much more connected than a mere moment on a chair in a room. But when it’s me wanting that to be more, then all you end up with is just the wanting. And that’s not a very attractive thing, in love and in life. Maybe that’s a good note to end on. ❚