The Art of Unruly Ruling

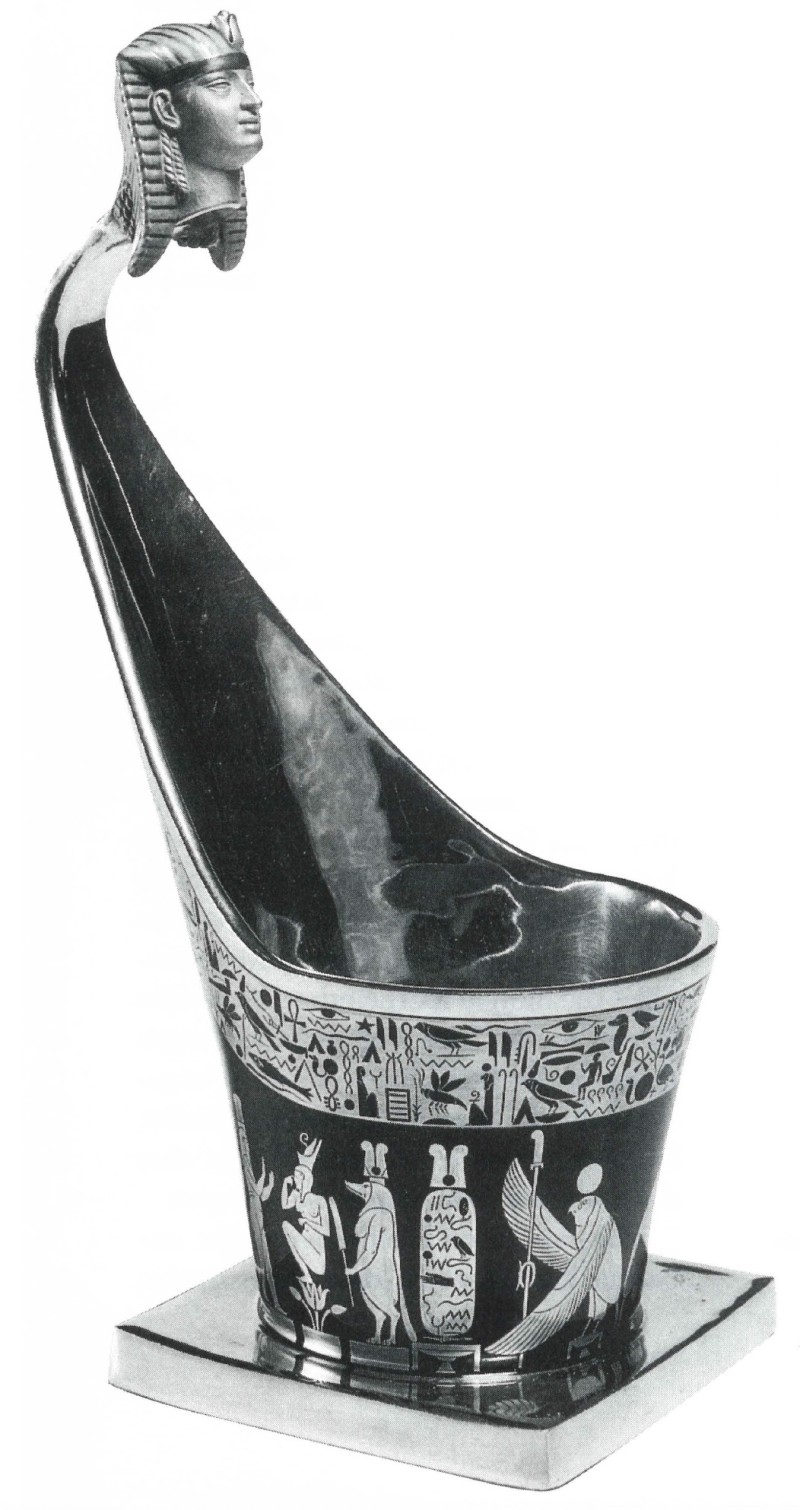

Cast off the shackles of ‘period’ and ‘national style’. Egyptomania, the frenzy for things Egyptian, is another kind of game whose rules long ago predicted what we now call ‘appropriation’. Certain cultural conditions encourage the production of art and interest in Egypt is one of them: a bottomless well of unfathomable mystery and palpable excess. The decisive curatorial factor before this embarrassment of riches was not the borrowing of Egyptian imagery but its transformation by European and North American artists of the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries. The exhibition traces the shift from polity to culture, documenting the subjugation of one powerful system of rule to another and the subsequent migration of an invented Egypt from the corridors of power to the drawing rooms of conspicuous consumption. Appropriately enough, “Egyptomania” the exhibition, has made a similar journey, from its inaugural staging at the Louvre in Paris to the National Gallery in Ottawa where the concept has matured and takes its ease in more generous surroundings. The catalogue lists 392 works (350 of which are on exhibition in Ottawa, the only North American venue for the show) including paintings, sculptures, prints, drawings, furniture, wallpaper, porcelain and jewellery. Punctuating this spectacular display are 25 solemn reminders of the civilization. Tactfully distinguished from their derivatives by the hieroglyphic symbols on their labels, the ancient objects are placed to stimulate both formal comparison and reflection on the evolution of symbols. The so-called canopic jar, for example, was designed to contain the entrails of the Pharaoh or one of his followers. As part of the process of mummification, it helped to perpetuate the life-force of the deceased. Such a friendly form was never meant for mourning, or so thought Josiah Wedgwood and others, rounding its profile to hold flowers, coffee or ink, or crowning the sons of Horus with nozzles to hold candles.

Canopic Jar, c. 1865, Josiah Wedgwood and Sons, Jasperware. Photographs courtesy The National Gallery, Ottawa.

From canopic jar to canopic vase is a relatively easy step. But tracing the spread of Egyptomania involves far more complicated mental gymnastics; we have to reach back to the Roman adoption of Egyptian cults in order to advance through the archaeological movements of the Northern Europeans and the adaptation of classical art and architecture fundamental to the Renaissance. In the 18th century, Rome’s synthetic Egypt formed part of the basic education of artists and architects who sketched and measured her monuments. Their subsequent emulations blended happily with copies and variants of Egyptian antiquities brought to Europe in the wake of the Napoleonic campaigns. Finally, add to these encounters the potent mixture of revolution and cultist revivals—the symbolism and ritual of the Freemasons and the mysticism of the Rosicrucians—which fuelled the desire for new pageants and mysteries, shaped the visions of oracles and designers, and spilled, finally, full-bodied onto the operatic stage. Egyptomania was, and is, an unruly phenomenon with sumptuousness its guilty pleasure.

The pretext, however, especially in painting, was directed by a higher order. Egyptian elements suited certain episodes from the Old Testament interpreted by Christianity as foreshadowings of the New. The finding of Moses by Pharaoh’s daughter, who saved the infant from slaughter, parallels the flight of the Holy Family into Egypt to avoid Herod’s massacre of the innocents. Both themes are represented in the exhibition. Egyptianizing furnishings and paintings assembled by a British collector of antiquities, Thomas Hope, included Louis Gauffier’s rendition of The Rest on the Flight into Egypt (1792). Affectionate demonstrations of angels notwithstanding, Marian serenity must have intruded somewhat upon Hope’s private pagandom. Egyptomania, by definition, encourages such transgressions.

For the exhibition in Ottawa, curator Michael Pantazzi could not resist a little prefiguration of his own, taking a short detour into the Baroque as a preamble to the 200 years covered by the exhibition. A Gobelins tapestry of the late 17th century, based on Nicolas Poussin’s The Finding of Moses (1647), replicates the postures of the women and much of Poussin’s carefully constructed Egypt. It disposes of a classical River God to make more of a Sphinx and perpetuates Poussin’s most obvious error, a monstrous sistrum. Poussin knew the shape of this percussion instrument, but not its use in the hand, so he gave it the dimensions of a violin. The diminutive prototype, a bronze arched sistrum from the Louvre, completes the prefatory sequence. This combination of objects is a brilliant introduction to the show with, on one side, conjecture and improvisation, and on the other, in a pride of sphinxes, a likely suspect for the very creature consulted by Poussin at the Villa Borghese. From this auspicious and complex beginning, a passage is led through the rich fantasies of Piranesi—theatrical, Egyptianizing residential interiors rivalling any stage set for “Aida” and “The Magic Flute.”

Sugar Bowl, 1810-1912, Sèvres hard-paste porcelain

Piranesi’s smoky, cerebral visions, like the imaginary tombs of Deprez, anchor an exhibition that will be memorable to most for its decorative arts. Here Emperor Napoleon is lionized through glorious reminders of his Egyptian campaign by “Citizen Denon” whose meticulous drawings of Egyptian monuments and artifacts turned into clocks, dessert plates, compote dishes and an immense architectural centrepiece including temples, colonnades, obelisks and 18 sphinxes in white biscuit porcelain. No reports of sparkling after-dinner conversation have been linked to this object (70cm high and 664cm long); only the echoes of astonishment from St. Petersburg where it was presented to the Czar. Miniaturization, delicate symbols and amazing views which were the charm of the Sèvres dessert service can be compared in Ottawa to a more ostentatious ensemble in bronze and cut glass, a group of candelabra, bases and tripods of Austrian manufacture. This is a gaudier, more eclectic otherness, where Egyptian and classical figures bear the weight of Imperial comestibles. Similar objects sifted down to lesser mortals and, finally, to the public at large as ‘Egypt’ assumed more malleable traits, conveying permanence, stability and authority in the stuff of cemeteries, bridges and prisons for a modern world.

Covetous dreams—then and now—could grow more sensuous by design, inspired by the discovery, in 1922, of the tomb of Tutankhamun. The sheer opulence of the loot and the intimate scale of the curios flowed naturally into the workshops of Cartier and Tiffany as the exotic element in Art Deco. Naturally, what was needed was a female model. She had already emerged in the various personae of Cleopatra, the beautiful, the tragic, the cruel. Some aspects, alas, are missing in Ottawa, but the ancient charisma is intact. Fraudulent in every respect, this Greek femme fatale was the precursor to Grey Owl—a foreigner in native’s clothing. Cabanel’s Cleopatra Testing Poison on Condemned Prisoners (1887), is surely the exhibition’s most amusing tableau as the evil empiricist, fanned by her attendant, weighs the effects of different potions in terms of efficacy and entertainment. By the early 20th century, the Western idea of Egypt was a blend of syncretic tradition and fashion. The legend of Cleopatra came to life, quickening the passions for perfume bottles and serpentine bracelets.

“Egyptomania” is complemented by an exhibition of 19th-century photographs by European travellers like Maxime Du Camp, Auguste Salzmann and John B. Greene who had moved as quickly as technology would permit to set up their cameras in the desert. Objective to the point of being dull, these so-called reports from Egypt and the Near East are nonetheless crafted by intention, eliminating scenes of contemporary life in favour of the isolated antique. Imperturbable as figurines, the Egyptians play their parts as staffage against crumbling reminders of their vanishing past. The curatorial selection is overlarge, but visitors to these exhibitions did well to begin their tour with a photographic sampling, the better to be amazed by such prodigious feats of Westernizing translation as a Sun God on his eternal circumnavigation of a bucket of ice cream. ♦

Martha Langford is a Contributing Editor for Border Crossings and lives in Montreal. She is a former Director of the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography in Ottawa.

“Egyptomania: Egypt in Western Art, 1730-1930” National Gallery, Ottawa, June 17 to September 18, 1994.