The 2010 Alberta Biennial of Contemporary Art: “Timeland”

Speaking to each other through the central sentiment of time past and passing, the majority of works in the seventh edition of the Alberta Biennial of Contemporary Art maintains a certain residue of primordial romanticism and technological intrusions. Beginning with Danny Singer’s evocative entrance video Rockyford, a near perfect encapsulation of small-town prairie life where time all but stands still in its humdrum progression, to Rita McKeough’s apocalyptic installation Wilderment, a work that literally puts us along the path of witnessing the growing devastation of our prairie grassland, “Timeland” attempts to present a view of Alberta that reads as both cryptic and urgent, straddling a consciousness of geological time and synchronicities.

Situating himself squarely in the role of a traveller coming into and across this land of hoodoos, coulees and urban sprawl, guest curator Richard Rhodes does not shy away from his stance of painting Alberta as a fantastical land before time. Stirring in awe of the Frank Slide remains in the Crowsnest Pass and gasping at the flowing interruption of the North Saskatchewan River, Rhodes adopts a curatorial strategy that forces us to reconsider these physical presences as playing heavily on the creative minds living and working in Alberta.

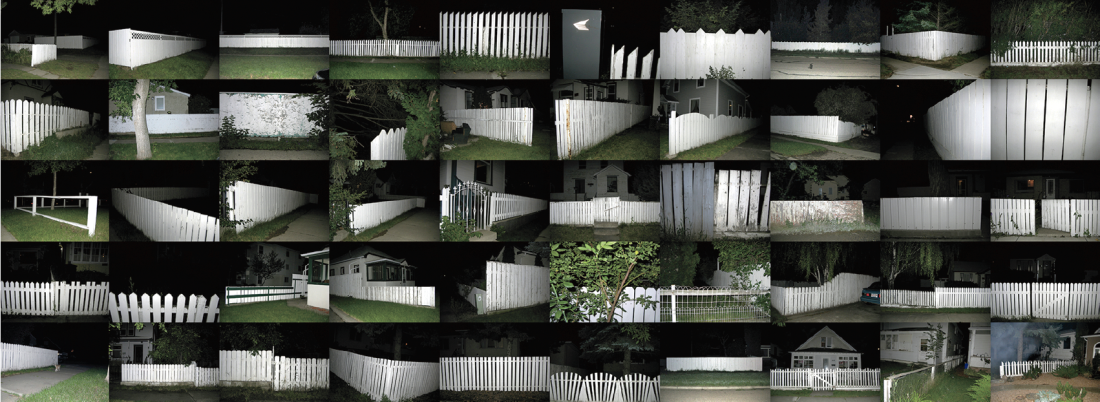

David M C Miller, White Fence at Night, 2010, inkjet prints. Courtesy Art Gallery of Alberta, Edmonton.

While this awe of the land is most evident in Rhodes’s curatorial framework, there is a large contingent among the 22 projects that appears to be more engaged in running across lines of rivalries, rumours and mythmaking centred around Calgary’s art scene. A major subtheme arising from this self-mythologizing is the cross-generational dialogue occurring between John Will and the next generation of Calgary-based artists, most notably Chris Millar. From the interplay of Will’s Anything and Everything, 1989–1991, a compendium that exists as a major anchor point in the show, one can draw the underlying foundation for the entire show: that anything and everything, once contrasted over a span of history and time, is still a summation of nothing new.

The curatorial vision may be deeply rooted in a somatic mystification of Alberta’s art and landscape, but the dialogue occurring between and across the works hinges on the notion of perpetuating artistic lineage, which unfortunately leads to an insular framework that also results in an imbalanced representation of gender, race and sexuality.

A more rewarding aspect, and the strongest curatorial choices, to emerge within “Timeland” is a consistent formal meticulousness that is curatorially understood as a constructive byproduct of the province’s modernist legacies. The time spanned and the formal detailing is evident from Jason de Haan’s Salt Beard to Millar’s Bejeweled Double Festooned Skull Plus for Girls, a hyperbolic sculpture crafted from the skins of acrylic paint and recently acquired by the National Gallery of Canada. Much like the disparate vastness of the province, the exhibition guide “Road Map” travels through a series of connected and disconnected eras and communities throughout southern and central Alberta.

Rita McKeough, Wilderment, 2010, mixed media installation. Courtesy Art Gallery of Alberta, Edmonton.

Inviting a non-Albertan for the first time in its 14-year history to guest curate the first edition of the biennial in the newly designed building, the Art Gallery of Alberta is shifting what has been a sometimes acrimonious provincial discussion into a national dialogue. As one of the first provinces in Canada to adopt the biennial model, Alberta has struggled in the past to contextualize an identity, one that ultimately came of age in the late modernism of 1970s and that still carries on a legacy of divide between the formalists and those who have come after. As a means to engage a cultural identity—forming by telling each others’ stories—the biennial finds itself in a stasis of identification, where one could only exist on either side of the formal divide—a portion that ultimately could not reconcile with its past and thus could not move ahead.

With that said, there were only a few works that express an interest in current identity exploration, shedding light into future possibilities for Alberta contemporary art. Notables include Wednesday Lupypciw’s unabashedly raw, Brazilian-Canadian video love affair Tranzar É Pras Amantes: Sex is for Lovers and Clint Wilson’s disarming 07-22-09, a video re-creating the solar eclipse with barely anything more than a penny taped to a wire. Compounding his desire and longing to witness this celestial glory through his construction of this makeshift eclipse, Wilson seeks out the sublime in his daily experiences. Paired with a soundtrack of a running shower slowed to the point of estrangement, the work is a meditative exercise in seeking infinite possibilities; in acknowledging our own limitations, it produces an ineffable self-made opportunity to experience the wonders of our existence.

While “Timeland” focuses less on Alberta’s diverse stories and representations, the exhibition does present a polished survey of successful artists living in Alberta, and marks one of the strongest and most cohesive group exhibitions put together on Alberta art, due in part to the vision of a single curator. ❚

The 2010 Alberta Biennial of Contemporary Art: “Timeland” was exhibited at the Art Gallery of Alberta in Edmonton from May 29 to August 29, 2010.

Amy Fung is an independent critic and curator currently based in Edmonton. She writes for print and online publications including C Magazine, Canadian Art, Galleries West and Akimblog.