The 15th Istanbul Biennial

Is a good neighbour someone who lives the same way as you do? Is a good neighbour a stranger you don’t fear? Is a good neighbour too much to ask for? These are some of the 40 questions posed by the radical and humorous Scandinavian duo Elmgreen and Dragset as their curatorial concept for the 15th Istanbul Biennial.

As a duo with a collaborative practice, it is perhaps natural that Elmgreen and Dragset worked to create a tight collaborative vision between the artists and the venues. With 56 artists, the Biennial is almost half the size of previous iterations. All six venues are within walking distance of each other, and each represents a different kind of community institution, making up a kind of neighbourhood: museum, home, hammam, workplace and school. The entire Biennial is like a mise en scène, with one work leading to another, all playing nicely with each other, like good neighbours ought to do.

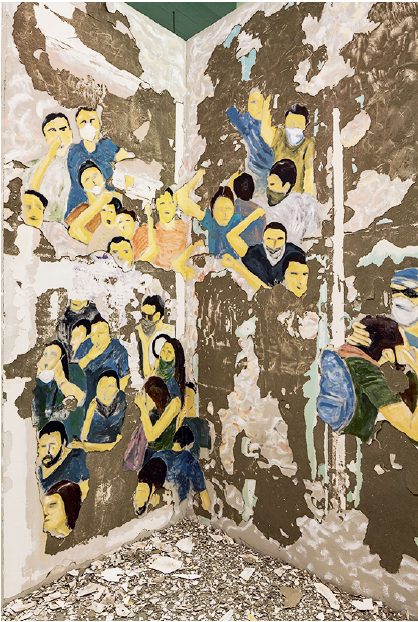

Latifa Echakhch, Crowd Fade, 2017, fresco, 365 x 2028 x 136 cm. Courtesy the artist, Galerie Kamel Mennour, Paris; Kaufmann Repetto, Milan; Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich; Dvir Gallery, Tel Aviv. Photo: Sahir Uğur Eren.

The Biennial’s initially banal-sounding title, “a good neighbour,” takes on greater pertinence in the context of contemporary crises of global migration as well as the unique geographical position of the Biennial itself. In a place like Turkey—which neighbours eight countries, two continents and two seas—the question of how to navigate the borders of daily life in a world of tumult becomes an appropriate focal point.

Turkish artist Erkan Ozgen brings this powerfully to the fore in his video work, Wonderland, which probes the human crisis occurring in Turkey’s largest neighbour, Syria. The seemingly benign short film shows a deaf 13-year-old boy using his body to gesticulate his horrific experience of being kept hostage by ISIL in Syria in 2015. Watching the boy miming terrible deaths and violent acts, we can almost be fooled into thinking we are watching a different boy playing at war with his friends in the schoolyard. But then we remember that this is not make-believe, and it is truly heart-wrenching.

Being a good neighbour is not a problem reserved solely for those outside one’s borders, however. The last year has been tense for Turkey internally, with a string of terrorist attacks, a failed coup and a state of emergency, all reflective of a global mood that seems to be dealing with stresses on internal cohesion while simultaneously questioning the robustness of democratic ideals in the modern world.

Fred Wilson, Afro Kismet, 2017, historic photographs, engravings and oil paintings; contemporary acrylic paintings and miniatures, late 19th-century Othello poster; anthropomorphic terracotta flask from the 3rd century BC, glass pendants from the 5th century BC; contemporary Iznik tile panels, carpet, chandelier sculptures, globe sculpture, blown glass sculptures; mid-20th-century wooden African mask, late 20th-century African figures, wooden false wall, birdcage, antique chair and table, wall vinyl, mounted photo scans, cowrie shells. Dimensions variable. Courtesy Pace Gallery and the artist. Photo: Sahir Uğur Eren.

Moroccan-French artist Latifa Echakhch’s magnificently large mural, Crowd Fade, is a pointed charge against such disenchantment. The falsely decaying mural stands as testament to the deterioration of liberal ideals like political process and popular protest. It begs the same question as that of the curators: What are the best ways of living together when you’re picking up the pieces of a life fragmented by conflict?

While the physical fragmentation of Echakhch’s mural acts as a signpost towards some of the conflicts faced by everyday people every day, Lebanese artist Rayyane Tabet and Algerian artist Lydia Ourahmane deal directly with these conflicts by critiquing property laws that damage neighbourly relations in their home countries on a daily basis.

The marble columns and concrete cylinders in Tabet’s installation, Colosse Aux Pieds D’Argile, come from a family home in the middle of Beirut, where the home was the site of a legal dispute between a real estate developer and the multiple owners of the house. The wily developer used a property law loophole to get his way: because a home with no roof must be either renovated or sold, he surreptitiously demolished the roof of the house, creating a situation in which he could develop on the site. A poetic work on how history is erased by architecture through laws, Tabet’s piece indicts capitalism for its contribution to the processes of ruin. It also levels a silent accusation, asking whether the multiple owners of the house could have been better neighbours and worked together for a better outcome.

Like Tabet’s, Ourahmane’s installation also uses commercial property to critique the subversion of the law in the name of capitalism in her home country. In Arzew, a small, Algerian industrial port city suffering from toxic emissions and pollution, a mix of a non-regulated real estate market and an expanded black market has made it possible to purchase contaminated land at low prices. Ourahmane’s piece, All the way up to the Heavens and down to the depths of Hell, is a 4 x 4-metre sculpture replicating one such plot of this land, demonstrating how land is used and transferred to the detriment of everyday people living under the negative forces of industry, environmental decay and the uneven distribution of wealth in post-colonial countries. For the individual living under these circumstances, the work is an invective on what it means to belong in such a place where the usually prized idea of owning land is reversed to show its dark side.

Rayyane Tabet, Colosse Aux Pieds D’Argile, 2015, 16 marble and sandstone columns, 19 marble and sandstone bases, 292 concrete cylinders. Each column 30 x 15 cm in diameter, installation 1,500 x 600 cm. Courtesy the artist. Collection Aishti Foundation. Photo: Sahir Uğur Eren.

While many of the works address contemporary conflicts, Fred Wilson’s work subtly turns the question on itself and investigates the origins of identity conflict. At first blush Wilson’s gallery-wide installation looks like a museum show, but on closer inspection it forces us to question how identity is put on display. In his installation— called Afro Kismet—Wilson locates the origins of Black people in the history of Ottoman culture in the slave trade, making us address our contemporary discomfort with medieval norms. Without expressing it directly, the work points towards the unexplored notions of conflict that undergird our daily relationships.

The entire Biennial employs this sort of minimalist language, with all the works dancing around the central question and critiquing serious contemporary human issues in creative ways. This is certainly a testament to the openness of the curators in their statement, which invited a diverse spectrum of imagination. It is also a testament to the timeliness of the central question. In a world plagued by clashes of ignorance, it is only by being better neighbours that we can hope to create more solidly cosmopolitan societies of co-operating civilizations. ❚

The 15th Istanbul Biennial was exhibited at various venues in Istanbul, Turkey, from September 16 to November 12, 2017.

Mohammad N Miraly is a published scholar and art collector. He holds a PhD in Religion, Ethics, and Public Policy from McGill University and serves on the Tate Modern Acquisition Committee for South Asia.