Thaddeus Holownia

In The World of Atget, 1964, photographer Berenice Abbott—who, as we know, once purchased and printed 176 of Atget’s photographic plates, thus recuing him from almost certain obscurity—writes, “The first time I saw photographs by Eugene Atget was in 1925 in the studio of Man Ray in Paris. Their impact was immediate and tremendous. There was a sudden flash of recognition—the shock of realism unadorned. The subjects were not sensational, but nevertheless shocking in their very familiarity. The real world, seen with wonderment and surprise, was mirrored in each print. Whatever means Atget used to project the image did not intrude between the subject and observer.” Abbott particularly stresses the degree to which “there was never any preciousness in his entire approach….”

Preciousness in art is difficult to keep at bay. The photographs making up the recent Thaddeus Holownia exhibition at Toronto’s Corkin Gallery—titled “Paris After Atget”—admit certain degrees of preciousness, ranging from a merely diverting tang of it in a photograph like Pont de Bir Hakeim (with its absurd, centrally positioned, pseudo-heroic statue commemorating the Battle of Bir Hakeim in 1942) to a good snooty wallow in it in one of Holownia’s graffiti photos such as Misstic—a photo-sample of the self-portrait stencil work of graffiti artist Miss.Tic.

Holownia has had frequent recourse, in the last few years, to homages and tributes to other artists—from American transcendentalist writer Henry David Thoreau (“Walden Pond Revisited,” 2004) to 19th century Scottish photographer John Thomson (“Working in the Dark: Homage to John Thomson,” 2014). Both of these projects seemed more successful than Holownia’s current Atget pursuit. It is probably important, however, to take note of the ambiguity that resides within Holownia’s title. “After Atget” could well mean “in pursuit of Atget,” thus locating the project as a photographic following-in-Atget’s-footsteps (track down the same sites and discover what has changed and what has remained the same). But “After Atget” could equally announce a photographic exploration of what changes time hath wrought upon the venerable city of light since Atget’s death in 1927. What has befallen Paris after the bombs of Modernism and postmodernism have been lobbed at it? It is this latter type of “After Atget” investigation that seems clearly to inform and tincture Holownia’s new Paris oeuvre.

Thaddeus Holownia, Misstic (cat), “Paris after Atget” series, 2007, edition 4 of 10, gelatin silver print, 40.6 x 50.8 cm.

Abbott calls Atget “an urban historian,” a “Balzac of the camera,” from whose work “we can weave a large tapestry of French civilization.” By diminishing contrast, the stuff of Holownia’s photographs seems to be about seeking out not the quotidian, but rather the mildly aberrant on the Paris scene (something Atget never did). Where Atget was curious and sociologically diligent, Holownia seems irreverent, sometimes to the point almost of prurience. Not a Balzac of the camera, then, but more a drifting photographic Françoise Sagan, maybe, or—at his best—asour-sweet Michel Houellebecq.

Which is to say that Holownia appears to be existentially uncertain of his mission: sometimes he seems to be Atget reborn (as in his photo of a majestic plane tree—Holownia is good at trees—in Parc Monceau). Sometimes he is half-heartedly and pointlessly mischievous, even affected, as when he photographs just the upper half of Charles Garnier’s Opera de Paris (Palais Garnier).

It is true that he channels Atget’s penchant for populist realism in his photos of storefronts: in his 12 rue Pierre-Lescot, a Dr. Martens store celebrating its 50th anniversary of proffering Airwair with a giant photo in its front window of high-haired singer Janelle Monae, and in his 14-16 rue Sainte-Croix-de-la-Bretonnerie, a queer sex boutique with a beefy, Tom of Finland graphic figure hovering near the doorway. But these bouts of photographic particularity seem more about bagging trophies than limning an urban landscape. Atget relentlessly photographed that upon which his vigilant eye fell. Holownia, working in the opposite direction, seems to begin with an eye hungry for that which will provide him with an interesting and hopefully curious photograph—a most anti-Atget idea.

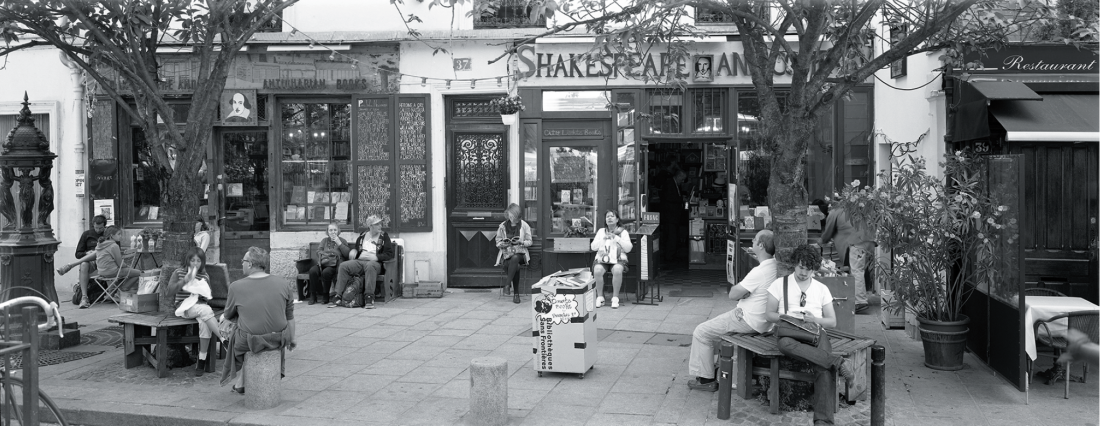

Thaddeus Holownia, 37 rue de la Bûcherie, 5e, “Paris after Atget” series, 2010, edition 1 of 10, digital pigment print, 38.1 x 91.4 cm. All images courtesy Corkin Gallery, Toronto.

Sometimes Holownia can be just less interesting—as he is with his Carrefour/Intersection avenue Daumesnil, rue Michel Chasles, et rue Traversiere, which seems dispiritingly ordinary (and too academically composed) when compared—in a comparison it clearly invites—to similar views by Alvin Langdon Coburn, André Kertész, Alexander Rodchencko and László Moholy-Nagy. Sometimes he is disappointingly banal, as he is in his 37 rue de la Bucherie, a genially ramshackle photo of the famous Shakespeare and Company bookstore, with the usual scattering of people sitting around outside, not looking interesting enough to bother with.

I think one of the difficulties with Holownia’s current Atget project is his clinging to the employment of his trademark wide Panavision format. The widescreen format might not seem so limiting if Holownia didn’t compound its artifice by so frequently using it to carry the radical symmetry he imposes on most of his chosen subjects. Almost all of the photographs making up the exhibition are built upon a rigidly constructed symmetry lying about the centre vertical of the photo and spreading out from it like equally weighted wings. This inevitably makes for the triumph of format over subject. Which is the last thing Atget would have permitted himself.

Louise Abbott reads Atget’s photographs as “realism unadorned.” Holownia’s Paris photographs come across as something precisely opposed to that: as something closer to artifice celebrated. Holownia is all style. But what I love about Atget’s photographs is precisely their freedom from the undertow of style, their exhilarating stylessness.

Okay true, Thaddeus Holownia is not Eugene Atget, nor, I expect, would he want to be. But the exhibition does rather solidly yoke them together—and, in so doing, generates a lot of thorny difficulties rather than proposing satisfying elective affinities. ❚

“Paris After Atget” was exhibited at Corkin Gallery, Toronto, from February 14 to May 4, 2015.

Gary Michael Dault is a critic, poet and painter who lives near Toronto.