Telling Details: The Painted Life of Salman Toor

One of the things that painting still tends to do better than other forms of pictorial art is express subjectivity. In large part, this comes from a lifetime of training in reading the works for signs of the artists’ personalities, their public concerns, private obsessions and psychological struggles. We have been taught to do this as a culture, over the course of more than five centuries. And as a medium, painting does lend itself to this sort of reading. The process—often a solitary communion or contest with the subject and materials, as well as the materials themselves—seems to imprint a visible trace of the artist’s interiority onto the support. Paint laid down on a surface frequently retains the index of the painter’s movements; observing the brush strokes, we can rehearse the artist’s gestures and decisions, recorded in sequence, like the “permanent memory-trace” to which Freud refers when discussing the “Mystic Writing-Pad.”

We know well that certain subjectivities have been privileged over others throughout history; painting proves no exception. The works of 37-year-old New York painter Salman Toor grapple with that history by manifesting a hitherto underrepresented subjectivity. Born and raised in Lahore, Pakistan, Toor studied art in the US, and limns a world of queer Brown men oscillating between South Asia and North America. Two paintings hanging side by side at the Whitney Museum of American Art in the artist’s first solo museum exhibition illustrate the cultural bifurcation Toor’s work straddles. In Tea, 2020, a scrawny, scruffy young man in patched jeans stands on the right at one end of a wooden table where a balding patriarch sits glowering and smoking, opposite a woman in a flowing garment who is looking over her shoulder at the young man. At the far end of the table, two more women (sisters? aunties?) stare glumly—one at the table, one at the family scene unfolding before them. The ensemble suggests the return of the prodigal son and speaks of generational and cultural gulfs. Certain details of the uncomfortable-looking young man’s appearance—a friendship bracelet, a knotted blue neckerchief, black-painted nails—intimate that we might read the son’s return as particularly fraught, a coming-out confrontation. The artist hints at the risks inherent to self-revelation in the bosom of a traditional family by illuminating the scene with an overhead light that resembles the one in Picasso’s Guernica and by having the mother grasp a small, elegantly curved sinister knife, with which she was just about to slice the fruit on a plate.

Salman Toor, Four Friends, 2019, oil on panel, 40 x 40 inches. Collection of Christie Zhou. Image courtesy the artist.

In the second work, Bar Boy, 2019, another young man, or possibly the same one, enters a lively gay bar, this time wearing a rakish broad-brimmed blue hat and staring into his smart phone’s glow. The wistful tilt of his head marks him as far more relaxed than his counterpart in the family romance, but he remains psychologically isolated, set off compositionally from the wedges of bar patrons to either side, who converse in groups, sip martinis, or dance in couples. Two fellows snog in the upper right, while in the lower left a man with long blond tresses rests his head in the crook of his apparently boneless arm, echoing the sleeping figure in Picasso’s 1931 Woman with Yellow Hair, in the Guggenheim.

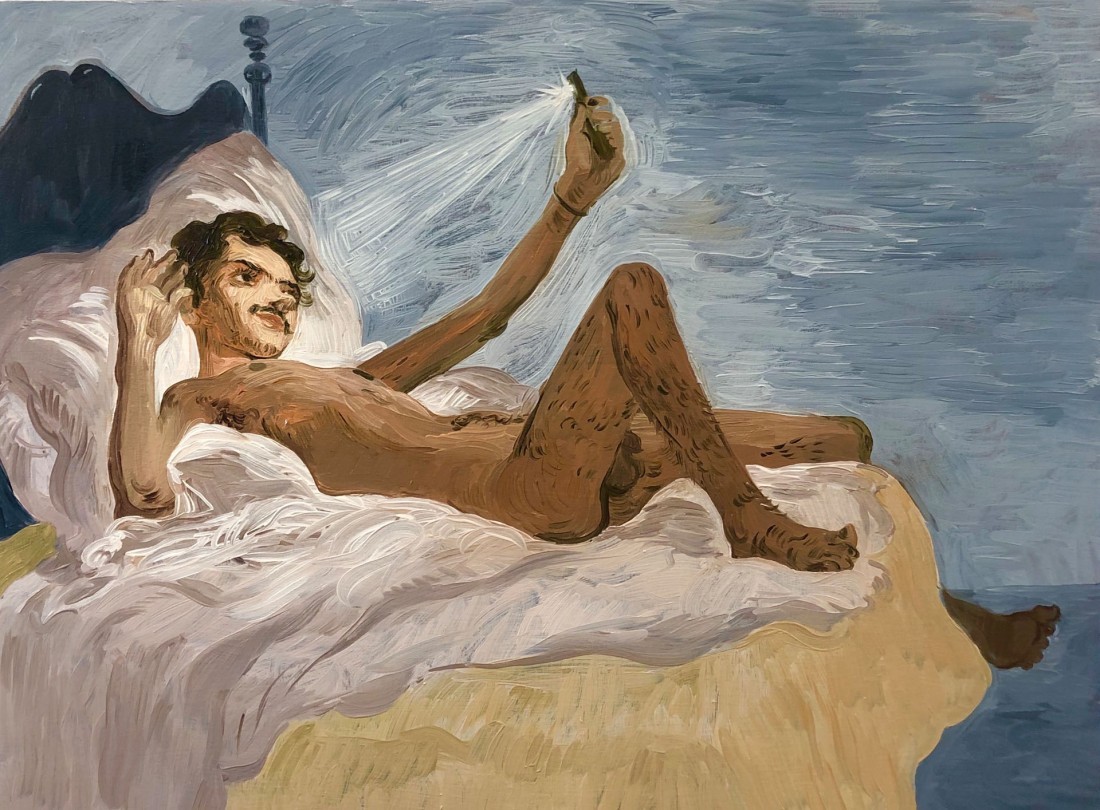

Toor’s recent works feature a recurring cast of characters, led by our protagonist, the thin young Brown man. We see him sometimes alone, naked in bed like an odalisque by Fragonard or Boucher but taking selfies or bathed in the incandescence of his MacBook. In other canvases, he gathers with a group of hipsterish friends, lovers and coevals in bars or small apartments in a North American city, dancing, embracing and playing with pets. Still other paintings show him back in South Asia, where queerness feels more furtive and male companions in parked cars can be accosted by uniformed police. Regardless of the setting, Toor’s scenes possess a kind of solemnity or quietude that does not suggest equilibrium so much as tender regard. Toor’s protagonists, obvious stand-ins for the artist himself, at least at an earlier moment in his life, seem held in suspension between two worlds, Old and New, never entirely at home in either. But he also holds them at emotional arm’s length, as if these images were tempered by time, less observations than memories, and they begin to assume the lineaments of archetype, despite their depiction of technology à la mode. Even a scene of violence, such as the ostensible gay bashing of Nightmare, 2020, one figure kneeling, one standing with a rock over our hero, who lies stripped, prone, beseeching, appears oddly calm, the pose of the figure on the ground recalling St. Paul in Caravaggio’s Conversion on the Way to Damascus.

Salman Toor, The Arrival, 2019, oil on panel, 18 x 14 inches. Image courtesy the artist.

Toor’s frequent, deft and often witty references to art history insert the explicitly ethnic, subaltern and othered vision of his work into the lineage of Masters, old and modern, while also indicating to us how to read his paintings. Another nightlife picture, for instance, The Bar on East 13th Street, 2019, presents an androgynous figure with beribboned braids, billowy sleeves and a mustache in place of Manet’s buxom barmaid in A Bar at the Folies-Bergère. Instead of the commodified sexuality implied by Manet’s web of looking, Toor’s image confronts us with non-binary queer desire. The customer, reflected dead centre in the mirror behind the bar, as if we stood there ourselves, in fact turns out to be the familiar young man, his appearance emphasized by his bright blue blazer in an otherwise largely green painting, a starburst of a disco light just behind his head. By positioning him as the literal mirror image of someone viewing the painting, Toor makes sure we know that his awkward everyman does not stand only for the painter but for every one of us as well.

The direct compositional quotations, however, mark only the tip of Toor’s deep engagement with artists who came before him, and his deftness and wit extend to the manner in which he paints. Some of his earlier paintings are more academic in their finish, but recent work shows his facility in the loosely articulated rubbery-limbed, long-nosed, somewhat cartoonish characters, not unlike those of painters of the 18th and 19th centuries who employed elements of caricature in the pursuit of social satire—Hogarth, say, or Goya, or, in the 20th century, someone like Reginald Marsh or Paul Cadmus. Toor has an eye for telling details; still-life objects and light sources often drive the narratives of his scenes. Many of the pictures have an overall green palette, appropriate, perhaps, for the nocturnal illumination of bars or apartment parties (although more readily suggesting fin de siècle gaslight), but also reminiscent of the discoloured varnish of old paintings hanging for generations in smoke-filled drawing rooms. Although part of an emerging cohort of rather dazzling queer figurative painters in New York and elsewhere, a group that includes Louis Fratino, Doron Langberg, Jenna Gribbon and Justin Liam O’Brien, Toor finds his closest affinities in terms of his relationship to the Old Masters in the figurative revivalists of the previous generation— Lisa Yuskavage and John Currin. By using his forlorn, self-conscious proxy as his leading man, Toor strings his episodic narratives into a kind of bildungsroman, iteratively insistent on our internalizing the subjectivity it manifests.

Salman Toor, Bedroom Boy, 2019, oil on panel, 12 x 16 inches. Image courtesy the artist.

A small series of paintings of men at airport security literalizes the liminal state that Toor’s subjects occupy; in travelling between one place and another, the men are obliged to display their possessions for officials we don’t see. In Man with Face Creams and Phone Plug, 2019, a striped scarf droops over the shoulders of a bearded man’s half-untucked white shirt, the phone, charger and lotions of the title spilling out onto a low counter. His downcast eyes suggest the non-threatening attitude that someone—especially a Brown male from parts of the world, like Pakistan, who would be labelled suspect—must adopt in such situations, but the downcast gaze also implies shame at the feminine contents of his pink toiletry bag, including scissors and a makeup brush. Two Men with Vans, Tie and Bottle, 2019, shows a pair (friends? brothers? a couple?) in a similar situation, but the small brown bottle next to a single slip-on sneaker has the familiar shape of a vial of poppers, again compounding the anxiety of travelling while Brown with that of disclosing one’s queerness. Tiny rays of light bounce off the bottle, giving it a halo, as the patch behind his head does for the man with the face creams.

Salman Toor, Puppy Play Date, 2019, oil on panel, 40 x 30 inches. Image courtesy the artist.

References to Western religious art pepper Toor’s works, but he doesn’t introduce such connotations glibly. Here, the association of intersectional identities or their signifiers with something holy transforms these scenes of airport checkpoints into something akin to devotional images. The stoic dejection of Man with Face Creams and Phone Plug, his halo, his display as a body subject to indignity and oppression, even the counter, which acts like the conventional ledge in Renaissance portraiture, makes him Christlike, a secular Man of Sorrows, presenting his corporeal being and the objects of his Passion. That the artist locates the viewer in the place of the security officer positions us as the judge, jury and possible executioner of the young men in these pictures. Ecce Homo. In fact, Toor’s depiction of queer Brown lives as being sacred, whether at the inflection points of systemic injustice or enjoying the simple pleasures of daily existence, may represent his most radical claim of subjectivity. ❚

Joseph R Wolin is a curator and critic in New York whose writing has appeared in Time Out New York, Glasstire and Garage Magazine, among other publications. He was recently the co-curator of “Living Together,” a year-long series of performance art, exhibitions, concerts, readings, lectures, workshops and film screenings at various locations in Miami in 2018, organized by the Museum of Art and Design at Miami Dade College.