Ted Barker

Walking into Ted Barker’s exhibition “Legacy” at Galerie Laroche/Joncas in Montreal, the first thing that came to mind was an involuntary but fascinating question that must occur to every viewer, one that the eyes and the mind start asking each other: Are what I’m looking at photos or drawings, or something else? There is a genuine and experiential sense to this query—especially from 20 feet away—which has nothing to do with any training we may or could have. Even when we do already know the answer, that uneasy sense of potential trickery and double identities turns out to be a real signature interest of the show.

The works (all from 2016) are virtuosic, beautiful drawings of heterogeneous subjects with one exception—an equally wellexecuted acrylic painting of a ghostly, fringed, hooded, empty coat that anchors the gallery space on its own smaller wall, between the two main facing walls of the room. Both longer walls are hung with five impeccable, framed pieces in graphite on paper. The sense is that perhaps they are painstaking facsimiles of moments from a quirky Facebook or Instagram page, or from a darkly comic Google search. But they also possess a nostalgic quality that recalls a family photograph album—which is what they somewhat are, thematically speaking. This quality is magnified by the frame-within-a-frame technique Barker has used, that makes the finely bordered, drawn portion of the paper look illusionistically as though it is a photograph stuck carefully to the white page of an album.

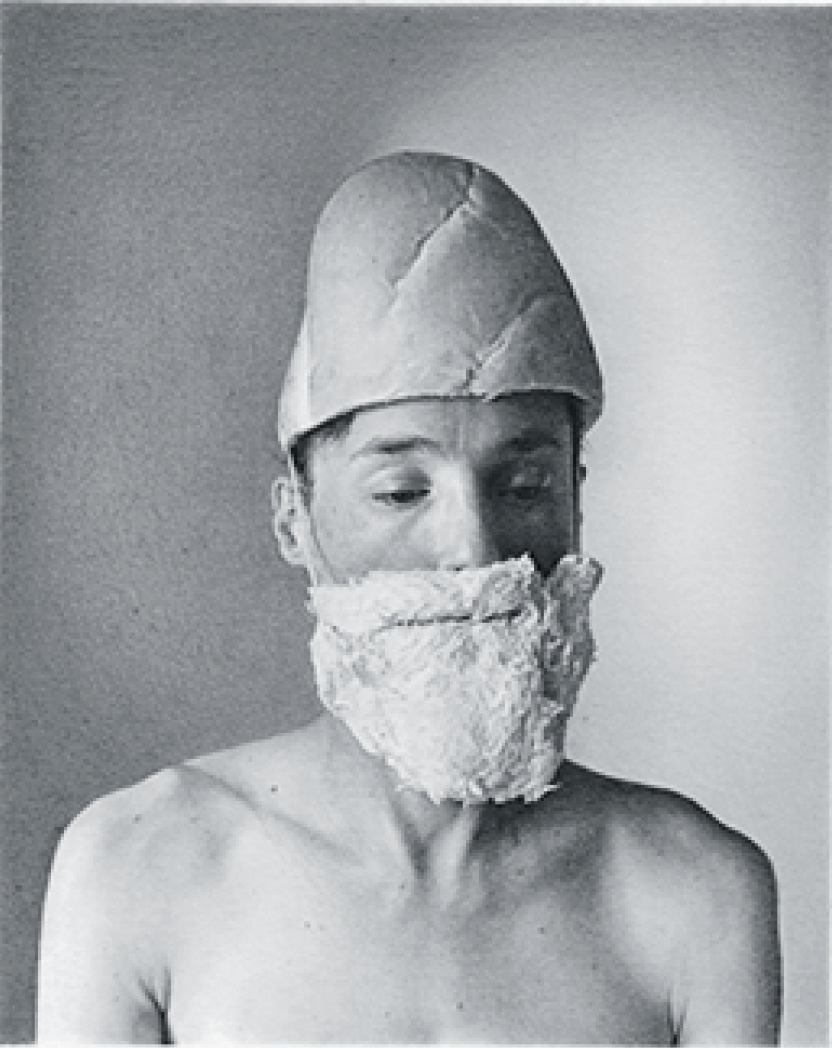

Ted Barker, Self Portrait as Robinson Crusoe, 2016, graphite on paper, 14 x 11 inches. All images courtesy Galerie Laroche/Joncas, Montreal.

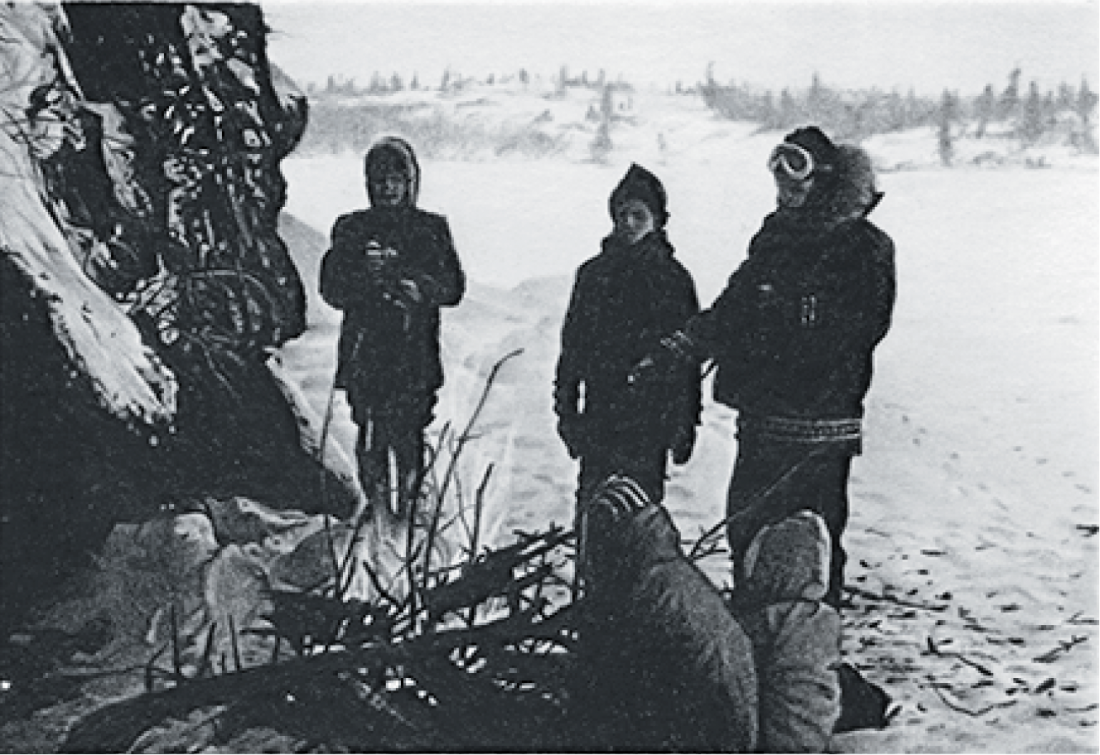

The “legacy” in question is that of Barker’s now deceased Opa (grandfather), whom the artist grew up knowing and loving, and whose coat is depicted in the painting described above. The images in the show were all done from carefully set-up and taken photographs that relate to the contents of the house in Winnipeg where Barker’s grandfather lived, crammed with the things and memories of his Opa. As a child he admired and believed in the rough manner and esoteric lifestyle in which his grandfather had chosen to exist, which involved living in a secluded cabin in the woods of Ontario for half the year (the rest of the family lived in Winnipeg year round). His grandfather was in fact a comfortably affluent man who had no direct reason for this doubled, or dichotomized existence. That is, other than choice, which he decided to adopt after immigrating following the Second World War from the Netherlands to Canada, where he took to the romantic myth of the rugged outsider. Because this was a situation that was presented in authentic and unquestionable terms by his Opa, Barker began to feel confused and uneasy about his grandfather’s identity, and from there came to question his own. Over time the artist in Barker prevailed and the project has taken shape.

The interior, visual qualities of Barker’s drawings show exceptionally patient attention to detail. Even more to their credit, they are executed in a free and sensitive manner. There is neither stiffness nor excessive coldness as a cost for such precise lucidity. It takes weeks of carefully patient rendering by Barker to do a single drawing of some few square centimetres, a process which requires a tremendous ability to know the steps of the process in advance, and to deploy them at exactly particular moments. There is no trace at the end of a drawing that shows any indecision, corrections, erasing or almost of the making itself.

Ted Barker, A Hundred Life Histories, 2016, graphite on paper, 14 x 11 inches.

The meaning of the show resides in good part in Barker’s questioning, in manifesting the duality of his grandfather’s identity, and his own in distinction to his forebear’s, as well as in the vacillating ocular qualities of the works.

There is an overflow of content, upbeat and humorous in its tenor, that quietly emerges in “Legacy.” Self Portrait as Robinson Crusoe (where Barker seems bemused to be caught wearing a hat and fake beard which appear to have been made from a loaf of bread), or Little Axe (in which a hand holds a tiny axe) both possess their own sort of quirky emotional atmosphere (Little Axe seems Lilliputian, and so maybe there are more references to the 18thcentury English novel here than it seems—with attendant, questionable romantic explorertype tropes). The show balances on a productive edge, between closed cipher and open book, where that initial mimetic ambiguity takes on a greater importance. Here, at least, in the possibility of our deception about the past or about history, about ourselves and our families, is a narrative smokescreen that reveals some truths in the act of exposing the closeted nature of the past. Maybe our anguished, contemporary, ruined sense of the real, or what’s real, our fear of, but also our possible revelling in, simulated reality is what the real already is, and always was. ❚

“Legacy” was exhibited at Galerie Laroche/Joncas, Montreal, from November 17 to December 22, 2016.

Benjamin Klein is a Montreal-based artist, writer and independent curator.