Takao Tanabe

The retrospective exhibition “Takao Tanabe” and its accompanying publication constitute a timely measure of a long and distinguished career in art. Born in 1926 in Seal Cove, a fishing village on the northern coast of British Columbia, Tanabe has been producing paintings for six decades. He has lived in many places in the United States, Canada and Great Britain, exhibited widely and been an active member of various arts communities (he helped to found the Arts Club in Vancouver in the 1950s and, with printer Robert Reid, undertook a number of fine arts publishing projects in that city). He also has played an active role as an educator and administrator (he directed the art program at the Banff Centre from 1973 to 1980, establishing its seriousness as a place of education and project development for artists), and an advocate for his colleagues (he figured prominently in the creation of both the Governor General’s Award for Visual and Media Arts and the Audain Prize for the Visual Arts). He himself has been the recipient of the Order of Canada, the Order of British Columbia, the Governor General’s award and two honorary doctorates. Such contributions, advocacies and accomplishments, however, are footnotes to Tanabe’s art itself and his determined quest for personal expression.

That quest has taken him through various levels of art education in Winnipeg, New York, London and Tokyo, and also through a kind of reverse historical progression, from the lively and inquisitive abstract expressionism of his early career to the immense, representational painting of his later decades. The latter has evolved from loose, washy works of evocative colour and form to realistic and highly detailed depictions of landscape. Many of Tanabe’s recent large paintings compass vast, lonely views of Canada’s Pacific coast: misty, rainy and leaden skies and bodies of cold, grey water, between which hover mountains, forests and islands. In this exhibition, such scenes are complemented by equally vast views of unpeopled land in Alberta, the Arctic and the British Columbia interior. The occasional suggestions of human incursion into the landscape—a few weathered pilings standing near the mouth of a river, the corner of a fenced field on a high plateau, a trace of rough, unpaved road across an arid hillside—seem almost incidental to the wider scene. They’re slight and ephemeral claims to ownership within a geological vastness of time and place.

Takao Tanabe, Dawn, 2003, acrylic on canvas, 137.4 x 304 cm. Collection of the artist. Photographs courtesy Art Gallery of Greater Victoria.

In an interview with me some years ago, Tanabe stated that he felt a deep “kinship” with remote and mysterious places. My theory is that, consciously or not, he was attracted to vistas uncontaminated by society and its injustices. I saw this—and still do—as a function of his personal and social history. At the age of 15, he was incarcerated, along with his family and thousands of other Japanese-Canadians, in an internment camp in the BC interior. Displaced, dispossessed and furiously disillusioned, the young Tanabe developed an angry mistrust of his fellow human beings. In some of his paintings, this mistrust appears to express itself in both a modernist sense of existential alienation and a postmodern awareness of otherness. Still, in works such as Errington: Autumn Sunset, 1988, and Dawn, 2003, a 19th-century note of the Romantic Sublime has stolen in through an apocalyptic sunset against black clouds and bristling, silhouetted fir trees, and, later, through pillars of celestial light slanting through a heavy sky. Other than as unseen witness, humanity plays no part here.

The exhibition, curated by Ian Thom, cosponsored by the Vancouver Art Gallery and the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, and scheduled to tour, is well served by its catalogue. Actually, as is true of other institutional coproductions with publishers Douglas & McIntyre, this is much more than a catalogue: it is an independently functioning and beautifully designed book, with insightful essays by Thom, Roald Nasgaard, Jeffrey Spalding and Nancy Tousley, and a comprehensive chronology and bibliography (the latter compiled by the VAG’s Cheryl Siegel).

While reading through the essays, I had the sense that, in his early career, Tanabe encountered other aspects of racialized thinking—less brutal and more insidious than wartime internment—in the form of art criticism. During the 1950s and 1960s, a few artists and critics alluded in reviews to the Canadian- born Tanabe’s “innate” understanding of Japanese calligraphy and brushwork, as evinced by his early abstractions, an effect, presumably, of osmosis or “race memory.” Tanabe himself says that he was exposed to very little art, Japanese or otherwise, when he was growing up. (He entered art school in Winnipeg with the expectation of becoming a sign painter.) His first encounter with any calligraphic tradition was second-hand, through the Abstract Expressionism in which he was schooled in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Certainly, his 1952 watercolour Sky dances with writerly loops and squiggles, but it reveals more of a connection with Mark Tobey and other expressions of automatism than with Japanese calligraphy and sumi-e painting. Tanabe did eventually study the latter two traditions in 1960, during a Canada Councilfunded journey to Japan. Even so, he returned to Canada convinced that his cultural alignment was with the West, not the East. The only thing Japanese about him, he has said, is his appearance.

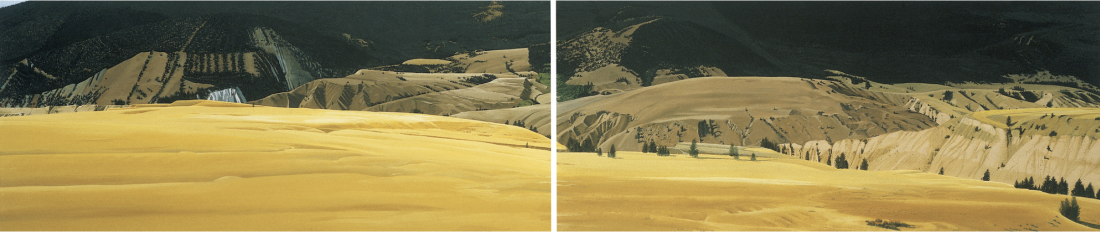

Takao Tanabe, Chilcotin 5/98, 1998, acrylic on canvas, 94 x 215.9 cm (x 2). Courtesy Scotiabank.

As you walk through the crowded show, it’s interesting to see Tanabe’s evolving relationship with the language of abstraction, from his early, experimental, organic abstractions in oil through his later ventures into hard-edge and geometric abstractions in acrylic (including shaped canvases and painted sculptures). It seems to me that, early on, Tanabe finds his most distinctive voice in Sun Over Swamp, 1964, and Grey Cloud, 1966, both acrylic paintings on paper and each composed of a bright or faint wash of colour in the upper part of the picture plane and a delicate yet energetic gathering of forms, colours and lines below. Nasgaard, among others, argues that much of Tanabe’s early work manifests a clear connection to the West Coast school of lyrical, landscape-based abstraction.

Still, having proven his prowess as an Abstractionist and insisted on its separateness from any landscape impulse, Tanabe gives himself over to that subject, in works such as The Land III, 1973, with its partitioned bodies of colour, inspired by aerial views of mostly agricultural countryside. (It’s also possible to see this work as an organic evolution of some of his hard-edge paintings.) The clearly divided representations of land in the northeastern US evolve into more subtle and evocative depictions of the Canadian prairie, in which Tanabe employs wide, washy, horizontal (and occasional diagonal) passages of blues, greys, golds and greens. When, after a long absence, he returns to the West Coast in 1980 (his home and studio are near Parksville, on Vancouver Island, although he also has a base in Vancouver), it is to fully embrace the beloved land—and seascapes of his childhood— the rainy, grey, mysterious vistas that speak of both primordial creation and primal awareness. He makes his own claim to realist painting by employing both the loose and largely abstract washes of colour characteristic of his prairie scenes (here used to depict sea and sky) with passages of extreme and particular detail (employed, for instance, to represent foreground waves or pebbles on a beach).

In Tanabe’s return to the West Coast as home and subject, there appears to be a certain degree of reconciliation. It’s as if the natural world (from which evidence of humankind, again, has been mostly expunged) were a place of psychological healing and spiritual renewal. This is, of course, an established romantic notion—but then it’s almost impossible to view Tanabe’s heroic landscape paintings without acknowledging their romantic grandeur. ■

“Takao Tanabe” exhibited at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria from October 7, 2005, to January 2, 2006. It is scheduled to travel to the Vancouver Art Gallery, the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia and the McMichael Canadian Collection in 2006 and 2007.

Robin Laurence is a writer, curator and a Contributing Editor to Border Crossings from Vancouver.