“Szilasi & Szilasi”

This exhibition of work by Gabor and Andrea Szilasi offered a long-awaited opportunity to appraise the work of two related but very different photographic bodies of work. Born in Hungary in 1928, Gabor Szilasi is one of Canada’s best-known and most respected living photographers. Soon after settling in Montreal in 1959, Szilasi continued the photographic work that he had begun years earlier in Europe. His riveting photographs of Montreal art openings (which he regularly attended with his wife, artist Doreen Lindsay, and also his daughter, Andrea, when she was young) were recently shown to acclaim at the McCord Museum— and that is only one facet of his expansive corpus.

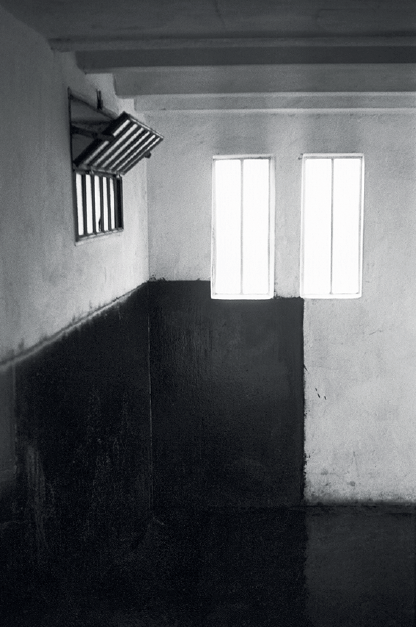

Gabor Szilasi, Public Toilet Budapest, 1954–56, digital print, 16 x 20 inches. Images courtesy Andrea Szilasi.

The present exhibition is a wonderful pairing of Gabor and Andrea Szilasi, who just happens to be his daughter, a noted photographic artist in her own right. Like many other fans of both Szilasis, I was waiting for just such an exhibition that would place both bodies of work in dialogue. The most striking revelation here was not similarities between the artists— and there are salient similarities in the depth structures of their works (such as a kindred integration of textual elements and a great love of black and white)—but their differences. It is precisely what sets them apart that speaks, I think, to the deep and abiding respect that Andrea has for her father’s work and which transcends, I think, familial love and related considerations. She went her own way right from the outset, and her work proudly stands alongside that of her father with shared resonance, gravitas and staying power.

It is remarkable to realize that Gabor Szilasi has been a critical voice in so-called straight photography in Canada for 60 years. The black and white photographs drawn here from his personal archive (many of which have never been exhibited before) are, simply put, a must-see and include singular images that we are now compelled to add to the accepted canon of his masterworks taken in Hungary, Canada and elsewhere. This is not surprising, given the scope and tenor of his project, but alerts us to the fact that there is so much more to know and appreciate in his corpus, which seems well-nigh inexhaustible.

One such black and white image is Public Toilet Budapest, 1954–56, a stunning study of light and shadow, the windows in the upper left quadrant juxtaposed with the black tar (used to disguise the smell of urine) of the floor and wall plane. The pitch black blurs the distinction between the upper and lower quadrants of the image as though a black pit has opened up below. This image has decidedly sepulchral overtones and bears the imprimatur of the compositional eureka! that indelibly marks all his work. It’s an exceptional image by any standard.

Andrea Szilasi, Skull Tunnel, 2019, digital print on Verona mat paper, 43 x 28 1/2 inches.

If the unusual and thematic reportage aspect of his work we last saw at the McCord was a welcome eye-opener, the present exhibition of works by Gabor and Andrea in dialogical pairing is equally revelatory.

I have argued elsewhere that Gabor Szilasi is an aficionado of the human face—and fact. He is a humanist of a sublime persuasion on the go with his trusty Leica M6 in hand. We have only to study Réjeanne et Gaëtan Garon devant le restaurant Bellevue, Saint-Joseph-de- Beauce, QC, juin 1973, a remarkable portrait of a couple posed in front of a car. But his sensitivity is not limited to human beings and it encompasses a phenomenal breadth of subject matter. Other aficionados will tell you that his photographs of secular or profane architecture are a strong point. Many photographs of the built world entice. Taverne du Coin, Noranda, Abitibi, juillet, 1979, a gelatin silver print (which also exists in a colour variant not seen here) is one such image. His casual authority and clarity behind the viewfinder are predicated upon an optic possessing the uncanny ability to capture, crop and process the essence of things seen at lightning speed. No exaggeration on my part to suggest that he is a magician of light and his daughter a sorceress of shadow.

Gabor Szilasi, Taverne du Coin, Noranda, Abitibi, juillet, 1979, gelatin silver print.

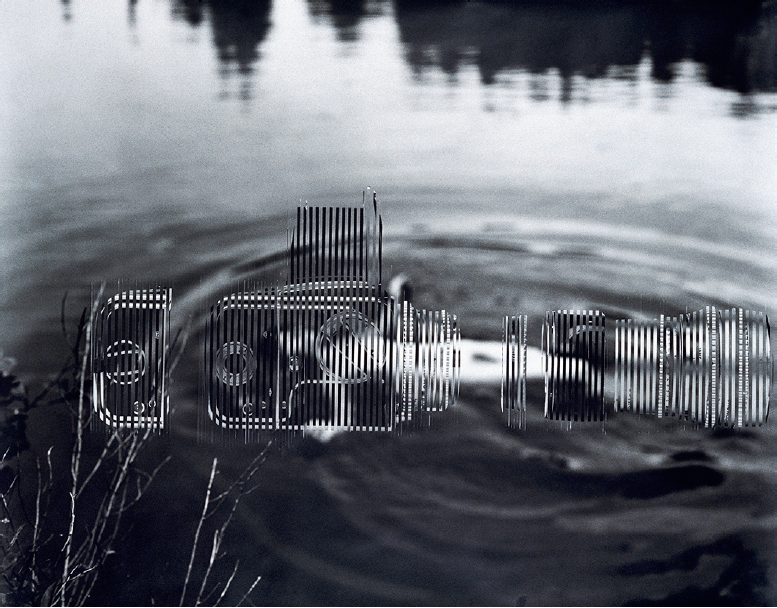

It is interesting to reflect on the fact that the mammoth photo work collage here by Andrea Szilasi, Body-camera in Lake, 1998, depicts a Hasselblad 500 C/M—one notably borrowed from her father’s toolkit, which includes his signature Leica M3 (his first), the Leica M4 (which we normally associate with his practice) and now the Leica M6, as well as a Sony digital camera, a Rolleiflex and even an iPhone camera he uses on occasion. These have been spliced and rewoven as a collage-in-part that is remarkably prophetic of much more recent photographic work that pushes the boundaries as to the definitional limits of the photographic image. Her interventions—cutting, incising, splicing, weaving, collaging—remind us of both what American experimental filmmakers like Brakhage, Belson and Smith did to their 16 mm film (gouging, burning, hand colouring, whatnot) and, more importantly, relatable contemporary feminist practices.

Andrea Szilasi is an inveterate and unstoppable experimenter, a photo-based artist whose work examines the representation of the human body in the photographic medium heightened and changed by non-photographic means. She is a collage expert of a photographic artist and one who consistently refuses to rest on her laurels.

These works all speak in thematic unison of the tremulous private body—often her own body, and so many of her images are then self-portraits— as a delicate armature for highly charged interior psychological states and a palpable harbinger of mortality. Her signature multiplication and mirroring of corporeal parts make for a magnified dimensionality that lures her viewers into the labyrinth.

Andrea Szilasi, Body-camera in Lake, 1998, collage (gelatin silver prints on fibre paper woven together, tape), 148 x 181 centimetres.

In her recent and ongoing series that features a human skull, such as Skull Tunnel, 2019, a digital print on Verona mat paper, and Skull Rock, 2019, Szilasi focuses with unsettling intensity on human finitude in stratified work that enjoys vertical depth.

She treats the body in terms of its primary status as lived, and this has very little to do with “realism” or straight photography. There is a conceptual agenda at work here that is distinct from formalism but no less interesting or self-present for all that. She dilates on the death event in a way that imports neither the stench of the morgue nor the sharp shiv of a conte cruel à la Octave Mirbeau. The handling of the human skull—an actual skull from her collection, with a wonderful patina of attrition and a demeanour of near ruin—situates it somewhere between anthropological evidence and the purely spectral.

Two gifted artists, Gabor and Andrea Szilasi, father and daughter and fellow travellers, open the brackets here not on family ties but on the past, present and future of the photograph. ❚

“Szilasi & Szilasi: Andrea Szilasi & Gabor Szilasi” was exhibited at Galerie Deux Poissons, Montreal, from October 17 to November 23, 2019.

James D Campbell is a writer and curator in Montreal, and is a frequent contributor to Border Crossings.

To read the rest of Issue 152, order a single copy here.