Swimming Upstream

Robert Frank, 1924–2019

Tuesday, September 10, 2019, 9:30 a.m. My wife, Cynthia, calls me to tell me that Robert Frank had died the day before. I’m grateful I learned the news from her. Nearly 30 years earlier, just married, young and finding our way, we moved together across the US—Tucson, Arizona, to Washington, DC—so I could take the job of my dreams, organizing the archive of the world’s greatest photographer-artist. Everything afterward in my life launched from that fateful decision.

I was always afraid of what I would feel when this day came. I’m about to introduce a press preview for a new exhibition season at the Ryerson Image Centre, but I’m overwhelmed with the shock and sadness. I get myself together, with real difficulty.

Robert Frank, Parade—Hoboken, New Jersey, 1955, gelatin silver print. © Robert Frank. Images courtesy Pace/ MacGill, New York.

I send text messages to the two people who gave me that job and introduced me to Robert in 1990: Philip Brookman and Sarah Greenough, the curators of Robert’s 1994 National Gallery of Art retrospective “Moving Out.” I’m curious that my first thoughts are for the people I met and hold dear because of Robert: his wife, the brilliant artist June Leaf, of course, but so many others, too, from his remarkable historian and bibliographer Stuart Alexander, to his devoted gallerist Peter MacGill, to his printers and longtime friends Sid Kaplan and Ed Grazda; and many others who’ve since passed away: Allen Ginsberg the poet, Walter Keller the publisher, Kazuko Oshima the jeweller, and Robert’s dear friend and devotee Kazuhiko Motomura, who published The Lines of My Hand in Japan. Over the next few days I won’t stop thinking of the interns who helped me organize the archive; the National Gallery’s brilliant team of exhibition designers, matter/framers, conservators and librarians; and the many people who selflessly supported my research, all those years ago.

Meeting Robert in late 1990 was the culmination of everything a young photography fanatic could imagine at that time. I remember encountering the job posting, during the course of an otherwise typical workday at Tucson’s Center for Creative Photography, with profound disbelief. I was at the beginning of what would eventually become a career, and this was an entry-level position at the national museum, cataloguing and rehousing and organizing the photography and ephemera of someone I considered a legend. Every day to be spent retracing his steps, building a chronology of his life and otherwise assisting the curators of his big retrospective. It seemed absurd to apply, and foolhardy not to. I felt it was unlikely I would be hired, so I just went ahead and submitted my application. I got the call, bought an ill-fitting polyester suit at Montgomery Wards, went to the capital city and braved the interview with Sarah. You can imagine how I felt when I got the job. I still can’t believe my luck.

Elevator—Miami Beach, 1955, gelatin silver print. © Robert Frank.

Shortly after I arrived in Washington, I went to spend a week at 7 Bleecker Street on the Lower East Side of New York City, where Robert and June lived part of the year, to prepare and pack contact sheets, negatives and work prints for shipping to DC. I worked in an upstairs room with thin, dirty windows overlooking a littered space between buildings. Cold air leaked through the putty, chilling the rusted filing cabinets, jumbled photo boxes and Polaroid negatives strewn across the floor. I slept on a foam slab Robert found in an alley and showered in a tiny cold-water stall, left over from the building’s days as a tenement rooming house. Robert and June were very kind to me, tolerant of my naïve excitement, and patiently answered my many questions. Robert guided me around the neighbourhood: one morning he shook me awake and took me for breakfast dumplings in Chinatown. After another long day of work, he gravely instructed me that I should see Frederick Wiseman’s Titicut Follies at the nearby Anthology Film Archives, so off I went. The next night, we had dinner at the now-defunct Noho Star; I’ll never forget watching Robert peel $20 off a fat roll of bills to pay the tab. All of it seems even stranger in memory than it was to experience.

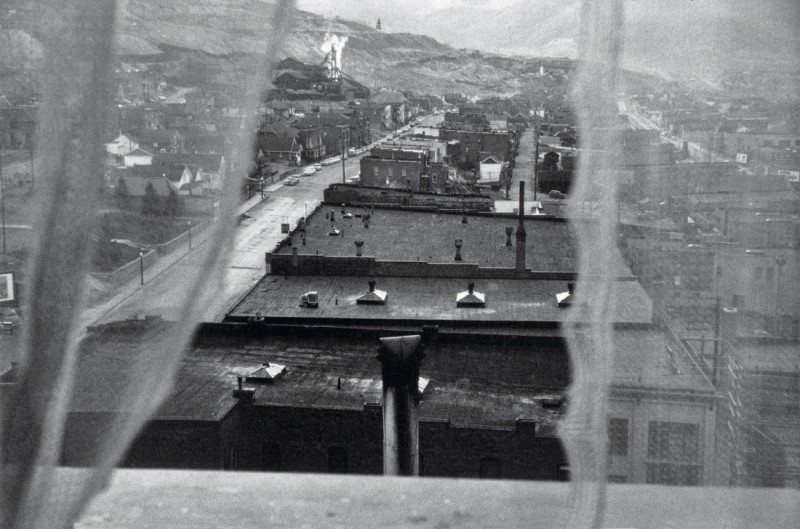

For the next four years at the National Gallery, I thought about Robert and his work every minute, every hour, every day. It was my job, but it was also an obsession. I painstakingly catalogued and rehoused the photographs and other elements of the archive. I found I loved the primary research, deciphering Robert’s handwriting on correspondence and his tattered file folder tabs, and tracking down obscure articles for Sarah’s and Philip’s research. I checked in frequently with Stuart Alexander, and sometimes called Robert directly, to make sure I was on the right track on key questions. I scoured old maps and newspapers to retrace his Guggenheim-funded route across the US, spent weeks correlating his work prints to the original contact sheets from The Americans and deciphered his annotated book dummy so we could reconstruct an earlier draft of the legendary picture sequence. It was an education far beyond your typical photo history class.

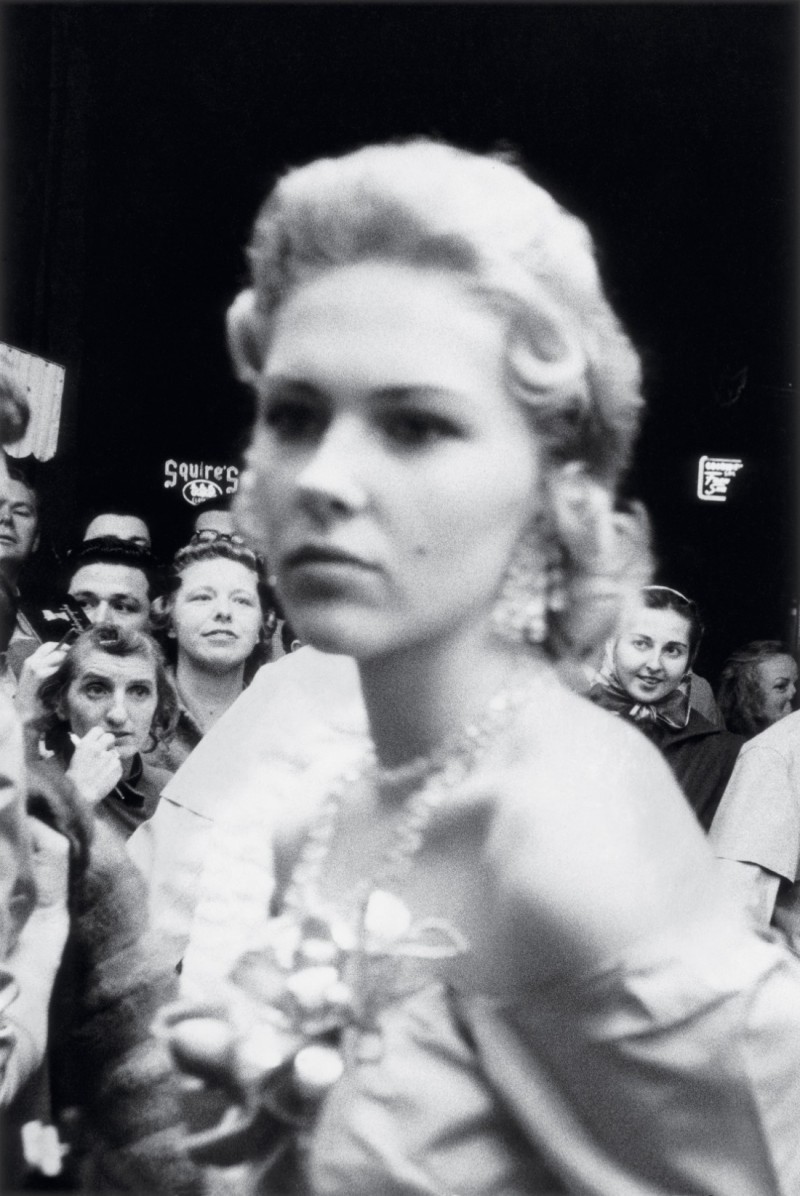

Movie premiere—Hollywood, 1955, gelatin silver print. © Robert Frank.

Most importantly, however, I was learning from Robert. I learned facts, chronologies, theories, biography in the service of my cataloguing; but I also ran into the myths, Robert’s tall tales and many broken leads—stray details that fascinated but led nowhere. I learned the name of the car crash victim under the blanket from the pages of The Americans, and researched the shady Chicago fixer Robert captured at the 1956 Democratic National Convention, with his cigar and incongruous sunglasses. Most of the facts I sought eluded me: I tried in vain to identify the young couple just married in Reno, Nevada, and dreamed nightly of all the things I would never know. The more I learned, the more I felt further from, not closer to, the truth. At an early moment in my time in the archive, June wondered aloud how I could live with my obsessive prying after the details of someone’s life. Of course, she was right. I didn’t stop, and I loved every minute, but I couldn’t shake the sting of her words. Mine was a strange occupation.

By the time the retrospective was over, I had developed a restless dissatisfaction with nearly everything I read about Robert. The reviews of Moving Out followed decades of earlier writing about him, but most of the critics added little that was new. Few seemed to understand the historical and cultural context for his photography and filmmaking, or able to articulate the lasting power of his work. Robert’s ironic detachment from his importance and influence, his frequently expressed mistrust of the regard people had for him, had by then cued me to be suspicious of my own infatuation. Even though I was the ultimate fan, I had learned from Robert to be wary of his lionization as a truth-teller, the ultimate outsider, the greatest photographer ever, author of the most important photo book of the postwar period, the solitary genius who travelled to the end of the road to escape the limelight. With everything I had learned, it seemed clear that the best way to regard Robert would be to assess him with clear eyes, as a working artist of his time and place. The last thing he needed was another acolyte.

When my work on the archive and exhibition was finished, I called Robert to say goodbye, telling him that I would be moving on. I sent him a tchotchke to remember me by, an oversized wooden model of a 35 mm camera, with a clock set into the barrel instead of a lens. In return, Robert sent me a photograph he made of window light on the walls of his workroom, shimmering above the bed I slept on when I stayed with him on Bleecker Street.

View from hotel window—Butte, Montana, 1956, gelatin silver print. © Robert Frank.

In the years after I left the National Gallery, and in the aftermath of my obsessive interest in his life and work, it is Robert’s middle period of searching, sometimes wrenching, autobiographical photography and filmmaking that has affected me most. His photographic collages and experimental films and videos from the end of the 1960s through the end of the 1980s are arguably as groundbreaking and influential as The Americans, having inspired and vexed generations of artists and audiences. Sadly, this rich passage of artmaking is often eclipsed by the shadow of his earlier brilliance.

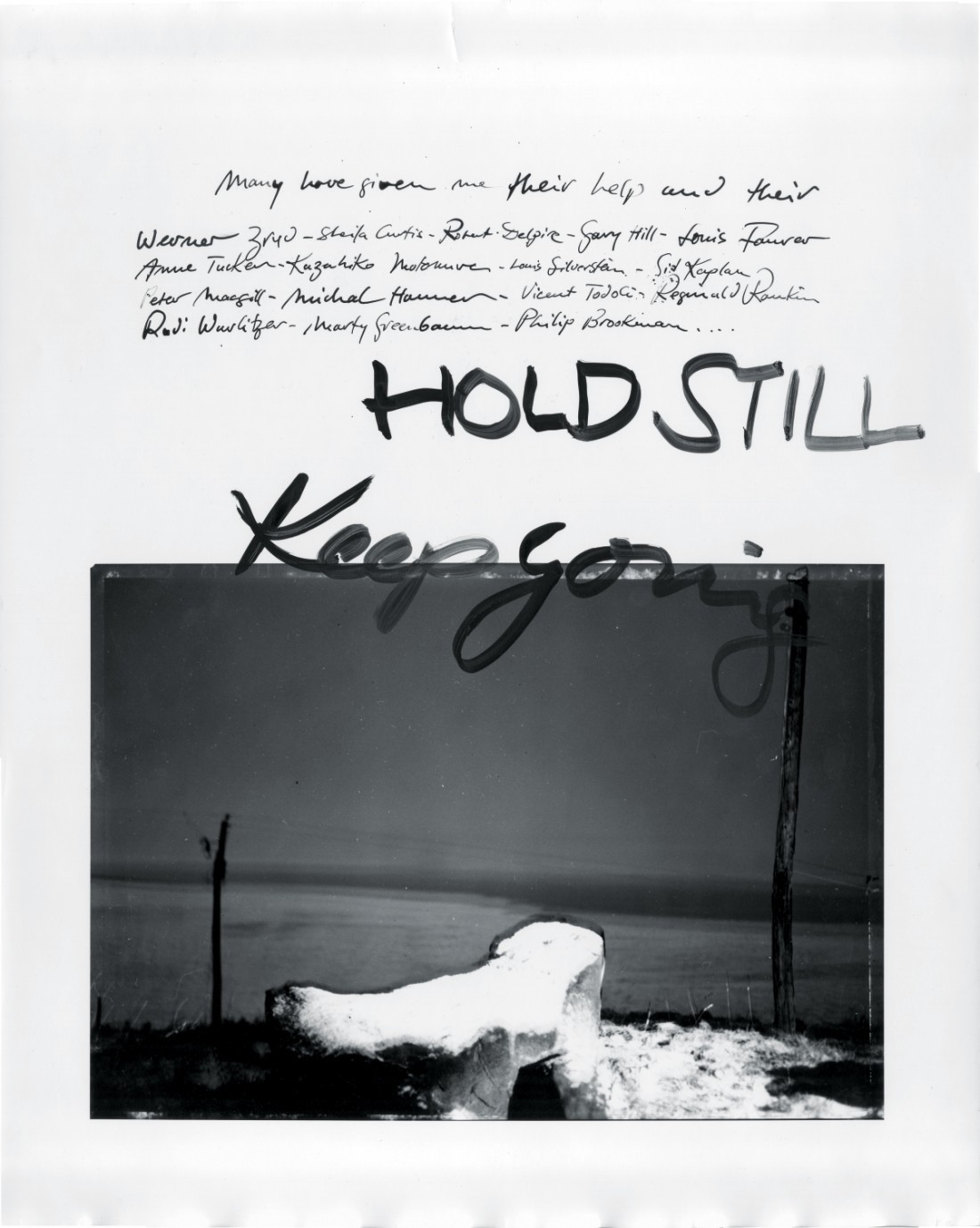

Robert transitioned from documentary to more personal modes of artmaking after moving to an old farmstead in Mabou, Nova Scotia, in 1970, trading New York’s rush and noise for a different pace and new frame of reference. In doing so, he recommitted to image making, but now as a kind of scavenger—collecting vistas, scenes and the minutiae of his life with non-professional photographic materials, from Polaroid instant photos to drugstore colour film in cheap cameras, as well as amateur Super 8 and video cameras. Observing and accumulating images as a daily practice, he would wait for a prospective idea to emerge from his raw material, and then experiment. He assembled these photographs and films with a new, rougher sense of storytelling, so they were both specific and richly metaphoric: layering and collaging multiple images, both colour and black and white, with visible edges, scratched surfaces and applied paint. Written messages issued forth in these piercing, diaristic bricolages: about the weather, landscape and the passage of time, and about his travels, visitors and friends, personal crises, painful memories, anguish and regret. There are many that are indelible, somehow both minor key in their personal scale yet monumental in their resonance: Isn’t It Wonderful Just to Be Alive, 1971, For My Daughter Andrea, 1975, Mailbox + Letters, Mabou, 1976, Sick of Goodby’s, 1978,Halifax Infirmary, 1978, and HOLD STILL—Keep Going, 1989.

Robert’s storied mistrust of artistic convention ultimately helped rewrite the “rules” of photography and cinema—rules he mastered as a serious student of applied photography in Switzerland. Seasoned technically and with a strong sense of pictorial organization, Robert nevertheless made a lifelong habit of departing from the norms, and from viewers’ expectations. Among his most significant legacies is the compelling way he merged still and moving images to make artwork somewhere between the two, and his incorporation of text into his photographs and films—whether handwritten or from a typewriter, scratched into the film emulsion or messily painted on the surface of his prints.

Convention hall—Chicago, 1956, gelatin silver print. © Robert Frank.

In his filmmaking, Robert established a unique voice and disjunctive style of shooting and editing, with overlapping sound and jagged scene transitions and a deliberate confusion between documentary and fiction. His earliest films were made in the cultural ferment of the avant-garde New American Cinema movement, presided over by Jonas Mekas, who also left us this past year. Pull My Daisy, 1959, and Me and My Brother, 1965–68, re-edited 1997, are indisputably among the landmark works of the period. As beautiful and memorable as those films are, however, Robert’s confessional middle period seems even more consequential. His diary films Conversations in Vermont, 1969, Life Dances On …, 1980, and Home Improvements, 1985, are like dirty pearls of self-revelation, laying bare Robert’s troubled relationships and concern for family and friends in crisis, and his wrestling with personal demons and his place in history. By turns playful and haunted, elliptical and ruthlessly honest, with mordant voice-over observations of the world around him giving way to raw inner monologues, these stream-of-consciousness films leaven the torment with a sheer heroism of persistence and a searching, offhanded beauty. Robert continued making short memoirs into his later period: his incandescent autobiographies Moving Pictures, 1994, The Present, 1996, Sanyu, 2000, and True Story, 2004, reinforce his legacy as an unsparing diarist, divulging a life beset by ghosts.

Despite the essential reflexiveness and solipsism (some would say self-indulgence) of his later photographs and films, Robert was an unsparing arbiter of his own efforts. He could be ruthlessly self-critical, especially about his filmmaking, in which he struggled against genre, perfection of form, the sentimentality of memory and, often, his original conception of a project. This feeling of perpetual misfire fascinated him, and he commented on it often. Robert’s “antidocumentaries” (such as About Me: A Musical, 1971, and Cocksucker Blues, 1972) and eccentric fictions (for example, Keep Busy, 1975, Candy Mountain, 1987, and Last Supper, 1992) draw their strength from their refusal to cohere or “succeed” as stories—an “aesthetics of failure,” in the apt expression of film historian Paul Arthur. As a result, the best of them achieve real moments of transcendence and epiphany without ever lapsing into artificiality, narrative falsity or redemptive meaning.

Halifax Infirmary, 1978, gelatin silver print. © Robert Frank.

Of course, as is now widely known, Robert turned inward only after exhausting his belief in the documentary photographer’s traditional role of objective observer. His 1940s–50s photographs from Peru, England, France and Spain were characterized by an unblinking romanticism and earnest beauty, and many picture editors in New York, London and Paris regarded Robert as immensely talented. But just as Bob Dylan was first perceived in the early 1960s as an agile inheritor of America’s folk song tradition, only to flip that tradition on its head in search of something greater, Robert’s mastery of traditional modes was a mere prelude. While he first sought success through publication in such magazines as Harper’s Bazaar, Glamour and Charm upon his 1947 arrival in the United States from Switzerland, he came to hate the chase for a living, souring on both the assignments and the culture of editorial photojournalism. Recalling the frustrations of this period for Wellesley College students in 1977, Robert said: “I had the influence of Life magazine. I wanted to sell my pictures to them, and they never did buy them. So I developed a tremendous contempt for them.… I wanted to follow my own intuition and do it my way, and not make any concession—not make a Life story. That was another thing I hated. Those goddamned stories with a beginning and an end.”

First published in France and then in the US by Grove Press—the rebel publishing house behind Beckett’s Waiting for Godot and Burroughs’s Naked Lunch—The Americans, 1959, is both the culmination of, and a lasting rebuke to, the certitudes and reassurances of the classical photographic essay. One cannot possibly understand its seismic impact without grappling with this reality. In its length, allusive complexity and allegorical ambition, The Americans took the idea of photographic narrative, developed in picture magazines since the 1920s as a hybrid of news illustration with elements of entertainment and enlightenment, to the outer limits of coherence and possibility, so that the traditional imperatives of storytelling were transcended and sublimated by a kind of visual poesy—in search of mystery and truth rather than factual account.

Read today, Robert’s original request to the Guggenheim Foundation to underwrite his project is astonishing in its audacity: “a broad, voluminous picture record of things American … essentially the visual study of a civilization.” Addressing his prospective funders, Frank boldly acknowledged the basic “absurdity” of his mission, “the photographing of America”: “One says this with some embarrassment but one cannot do less than claim vision if one is to ask for consideration.” Speaking at Wellesley, Robert was remarkably frank about his goals: “When I did The Americans I was very ambitious. I knew I wanted to do a book, and I was deadly serious about it, and somehow things just happened right. It was the first time I had seen this country, and it was the right mood. I had the right influences.… I knew what I didn’t want, and then that whole enormous country sort of coming against my eyes.”

HOLD STILL—keep going, 1989, gelatin silver print. © Robert Frank.

The Americans’ photographs of urban and rural America, of daylight and night, society’s insiders and outsiders, institutions and byways, flags and monuments, live on in large part because they balance a powerful objectivity of observation with an equally powerful subjectivity of insight. Robert photographed and then edited toward an uncompromising truthfulness, applied both to the soul and the mythology of postwar America. Few artists had the courage to face down the patriotism and exceptionalism of the US with such defiant integrity. One could argue that Robert’s subsequent fame simply exemplified a different (but equally patriarchal and pernicious) American mythos, that of the venturing, truthseeking male individualist, leaving society behind for the open road. Such a reappraisal may yet afflict his reputation; certainly Jack Kerouac and other figures of the Beat movement have been reassessed through this less-than-flattering lens.

No matter what, it seems certain The Americans will be celebrated far into the future. Gerhard Steidl told me recently that he sells many thousands of copies every year, that Robert’s book is still sought out by young photographers and art students at a critical moment in their education, as they question what they’ve been led to believe about the world. The Americans is an endlessly provocative book, its meanings somehow elusive and unresolved, yet inevitable, like Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane—other works of art that fascinate endlessly but somehow cannot be pinned down or fully grasped. Robert achieved this both in his tight selection from among the 20,000-plus photographs he made between 1954 and 1957, and in their uncanny visual succession. The pictures themselves seem to stand both inside and outside the context of their historical moment, describing places and people with great specificity and precision, yet timeless somehow. In semiotic terms, they seem perfectly balanced on a tightrope between the denotative and connotative, between signifier and signified. They are fascinating both as reports and allusions outside the frame, as representations and interpretations as the real and as the truth.

While The Americans didn’t sell well initially, the 1960s and 1970s brought a deluge of attention Robert’s way. As he faced the cultural power of his own creation, it is no mystery why he “burrowed ever more deeply into doubt and deliberate contradiction,” as author Luc Sante characterized his mid-career shift. How else could Robert forge a productive career, or make interesting art, without shaking free of such fame? His contrariness became legend, and many casual encounters, long-term friendships and working relationships ended badly. Despite his long reputation for being demanding and curmudgeonly, however, he was famously generous with many of his friends and collaborators, and could be remarkably warm to young artists. He and June routinely welcomed unannounced art students knocking on their doors at Bleecker Street and their remote Mabou homestead. There were many such visits through the years, right up to near the end.

Sick of Goodby’s. Mabou, November 1978, gelatin silverprint. © Robert Frank.

Robert’s receptiveness to his young fans often struck me as a puzzling dichotomy, standing in apparent contrast to his mistrust of fame. Looking back, I wonder if he saw students as standing apart from the art world he rejected, interested in him not because he was famous but because they saw in him a kindred protagonist, someone who bypassed the mythologies in search of truth. Maybe he mistrusted his fame not because it burdened him but because it limited him—in the same way that the documentary photographic image came, over time, to seem inadequate to his experience of life. After The Americans, Robert often critiqued his fame and the idea of the single meaningful image in similar terms. Both, he suggested, freeze the flow of time, close the door on progress, force one to look backwards and belie the most important aspect of life: that it should always, resolutely, move forward. Any expression, Robert came to feel, is meaningful only in its contingency to the onward flow of life and to the potential it expresses for hope—however faded, however thin. Fame, Robert once quoted Kerouac in Home Improvements, “is like old newspapers blowing down Bleecker Street.” And life, as he himself famously said, dances on. ❚

Paul Roth is director of the Ryerson Image Centre in Toronto, Ontario. He previously served as senior curator of Photography and Media Arts at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, and as executive director of the Richard Avedon Foundation. He is the author and co-editor of _Gordon Parks: The Flávio Story, Steidl, 2018._