Susan Feindel

When I entered Susan Feindel’s exhibition “See Below,” blackness enveloped me. Five circles of light, located to form a diagonal line across the floor, are all I could see, but they were enough to provide a calm feeling of arrival: no panicked groping for curtains or walls that is so often required in the darkened rooms of new media installations. The sounds in the room were impossible to identify, though they seemed familiar: water and wind, perhaps churning pebbles, interspersed with a more distinct clanking of small objects. There was nothing to disturb the sense of limitlessness, a feeling of being an integral part of this world. At least not in the first few minutes, before my eyes adjusted.

Slowly, walls and doors became perceptible, and on the floor five long canvases emerged from the darkness: they showed sharp, criss-crossed lines and fluid-oozing shapes in tonal black-and-white ink and wash. Next, I distinguished long cords with tube-shaped lamps hanging from the ceiling, each lamp creating an illuminated circle on the paintings. Beyond these spots, the paintings could only be dimly perceived.

“See Below” allows the viewer to imagine the impossible, what it’s like to walk on the ocean floor as if it were “no different from living in the earth’s atmosphere with its unfelt pressure on our bodies,” as Feindel wrote in her artist’s statement. Her means turned out to be low-tech: a tarpaper-covered floor, canvas, light bulbs and a soundtrack. No dazzling technology but simply my eyes slowly adjusting before I began to perceive distinct objects.

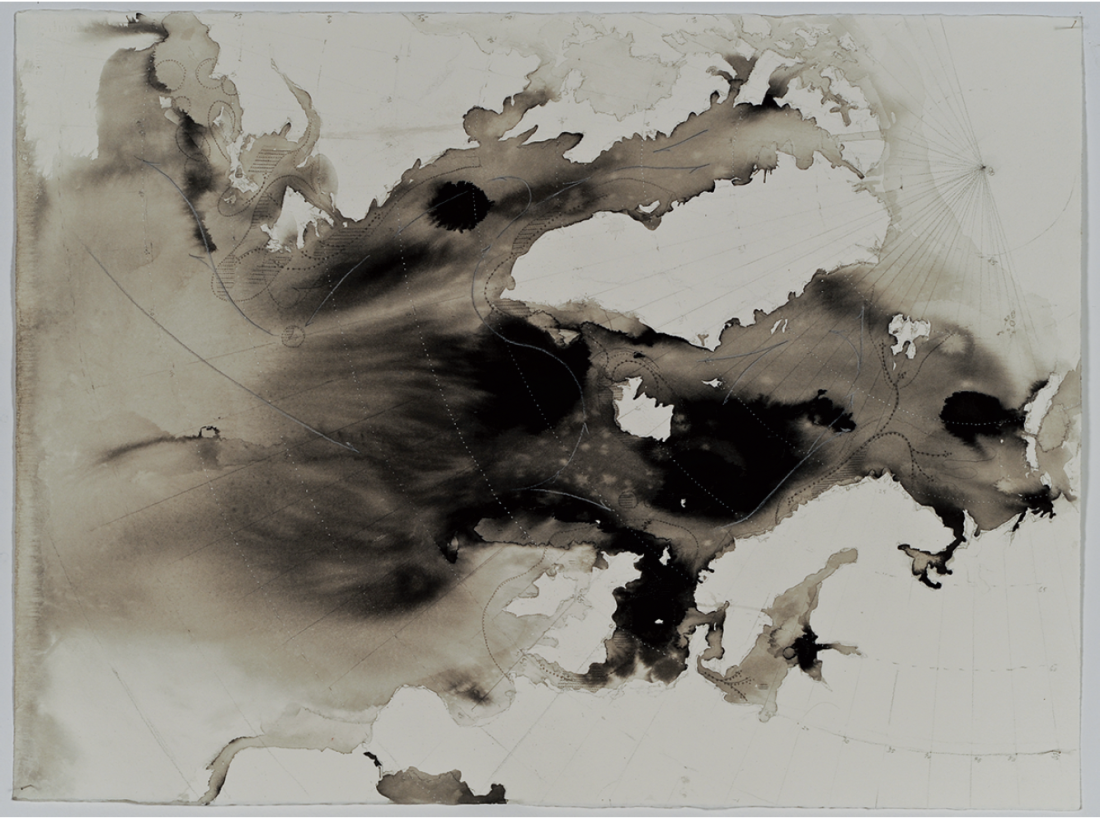

Susan Feindel, Perforation Map 1: Cod Migrations, North Atlantic, 2007, india ink with graphite, coloured pencils and needle prick perforations on rag paper. Courtesy of the Ottawa Art Gallery.

The writer Romain Rolland asked his friend Freud if he would discuss the oceanic sensation of the eternal that he thought all people experience sometimes, and which he saw as a source of religious energy. Freud, in Civilization and Its Discontents, claimed that he himself had not experienced that “oceanic feeling” of “being one with the external world as a whole.” He criticized it as a regressive yearning for an infantile consciousness without distinctions. He saw little use for it in adult life when boundaries between ego and object need to be kept in place in order to deal with an objective world.

Feindel, however, counts on the viewers’ familiarity with that sensation of limitlessness to establish an affective relationship—through sound and immersion—between them and her installation. Before she draws us into her ecological concerns about the ocean’s habitat, she lets us feel our deep connections to the world around us. While our eyes don’t let us dwell in the “oceanic feeling” long enough for it to turn into a regressive yearning for wholeness, this fleeting feeling is harnessed to encourage ecological care.

Her emotional, even seductive, presentation of what, in fact, is scientific data is what sets her apart from the scientists she relies on for source material. Feindel has accompanied oceanographers on several research voyages along Canadian and Norwegian coasts and has a deep appreciation of the curiosity, the sense of wonder and love for nature that scientists have in common with artists. The poetic title of the series of floor canvases comes from a scientist, not an artist: “It will smell like the breath of a new-born baby”(Anonymous, Aboard CCGS Hudson, 2001). These words were spoken by an oceanographer, one of a huddle of people on deck eagerly awaiting a sample of sediment being hauled up from the depths of the ocean. The words show the excitement of an encounter with something never perceived before and draw an analogy between the material of the ocean floor and the human body. The scientific data, the graphs and grids, maps and tables that are finally presented to the scientific world, however, are purged from all such emotions and anthropomorphisms.

Installation photo of Susan Feindel’s “See Below” with Perforation Map 1: Cod Migrations, North Atlantic, 2007, Perforation Map 2: Magnetic Reversals, Mid-Atlantic Ridge, 2008, Perforation Map 3: Eel Migrations, Sargasso Sea (Portugese Map, 1632,) 2009. Photograph: David Barbour. Courtesy of the Ottawa Art Gallery.

It is this dry data that Feindel re-invests with affect and wonder. For this she borrowed images produced through sonar technology and used by scientists to probe and map the ocean floor. Too deep to enter physically, acoustic pulses are transmitted from both sides of the ship to the bottom of the ocean. The pulses are then transposed into computer images on board. The technology works much like ultrasound on human bodies, a parallel that does not go unnoticed in Feindel’s work, which often brings up the similarities between natural organisms, human and non-human. Darker tones indicate a hard substrate, greys represent soft material such as sediment and living organisms, and white shows an absence of acoustic data. Sonar side-scan images show a white band down the middle where the ship obscures the signals. On her canvases, Feindel painted these mute spaces black.

Despite the magnification and painterly intervention, the paintings faithfully copy the scientific data, each one representing a stretch of the ocean floor. They reveal specific phenomena, such as natural oil leaks, tracks of fishing gear, iceberg scours and the less sound-reflective presence of soft marine life, such as coral reef.

In an adjacent gallery, similarly atmospheric, three tables showed ink-and-wash drawings presented on glass-topped tables lit by strings of lights beneath. These “Perforation Map” drawings represent marine maps from sources as varied as the National Geographic and the Institute of Marine Research in Bergen, Norway. The geographical information is shot through with innumerable pinpricks that sparkle with the light from below, forming flows that indicate routes of migrating fish and other natural phenomena. Feindel’s lyrical treatment of scientific data results in enchanting objects that are a tribute to both the scientific and the artistic imagination.

Nature has been the prime focus in Feindel’s long career that began more than 40 years ago when she graduated from Mount Allison with a degree in fine arts and related studies in music. The Nova Scotia artist has accompanied scientists on many research trips, on land and sea, in particular to areas where the ecology is endangered. The exhibition “See Below” was originally shown at the Mount Saint Vincent University Art Gallery in Halifax and was curated by Ingrid Jenkner. In 2009, it received a finalist award from the Lieutenant-Governor of Nova Scotia Masterwork Arts Awards. ❚

“See Below” was exhibited at the Ottawa Art Gallery from February 11 to April 10, 2011.

Petra Halkes is a painter, art writer and curator in Ottawa.