Sunil Gupta

The recent retrospective of photographer Sunil Gupta at Toronto Metropolitan University (formerly Ryerson) Image Centre, “From Here to Eternity,” is a deeply moving and visually stunning overview of a critically engaged and intellectually sophisticated artist.

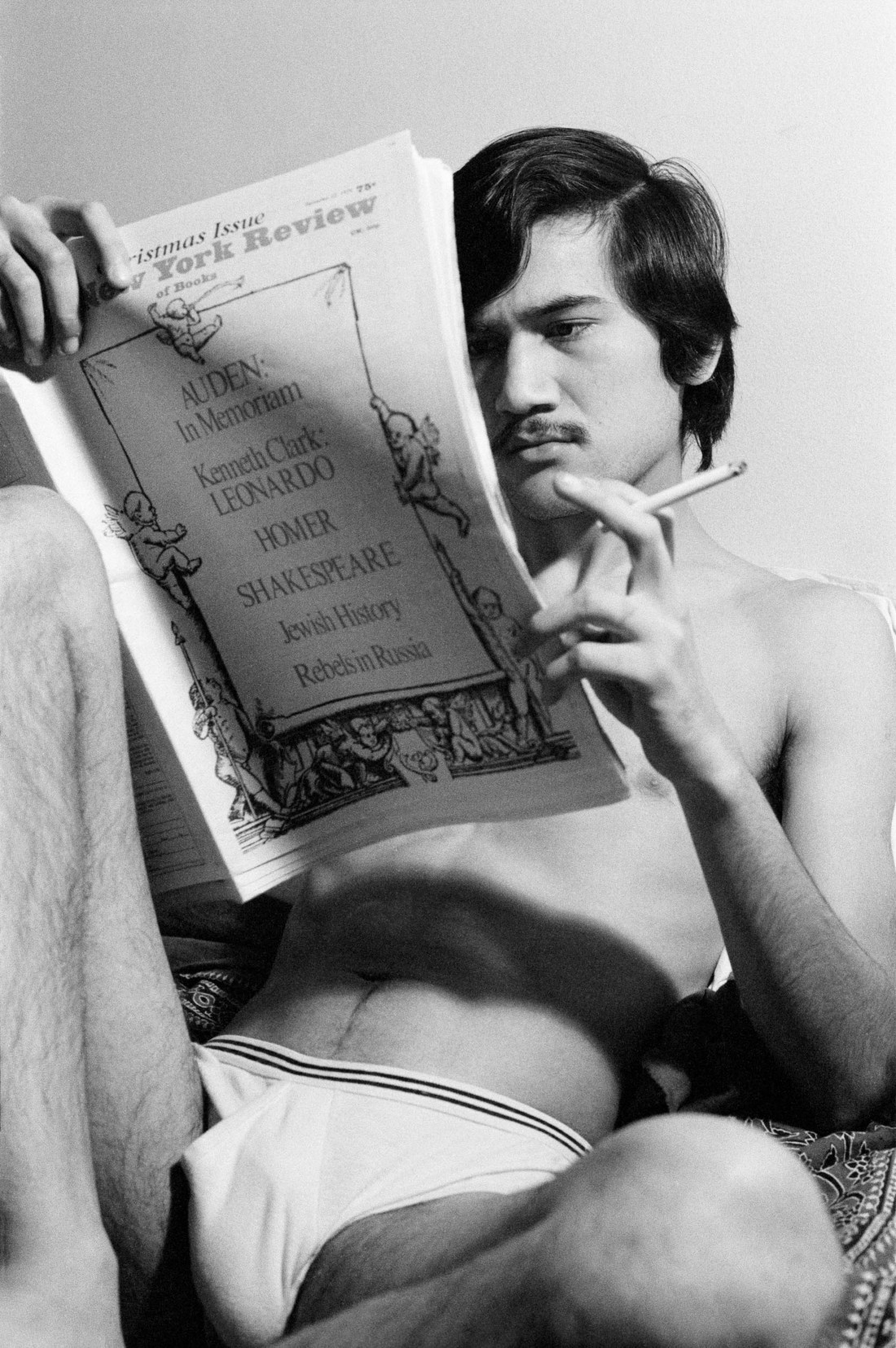

In the collection of photos titled “Friends and Lovers” from the early 1970s, Gupta eschews ethnographic detachment for intimacy. Appearing as a subject in many of the photos, Gupta insists on being a participant observer, one bound by ties of affection to the people in his life. Handsome, fit and dapper, Gupta is in casual familiar scenes—one dressed in a sports coat wearing a bright red and orange tie and a beaming smile, with his arm around a friend; another at a beach, sporting a white and blue striped bathing suit, embracing two other friends; and yet another sitting in his white y-front briefs, smoking and reading the New York Review of Books. Gupta works from the self outward, be it in his photographs of family, friends and lovers, or in reflecting on the complexity of Indian and diasporic queer belonging. These themes are not abstractions; they are part of Gupta’s quotidian reality and they untie the work in a compelling visual narrative that is simultaneously biographical and historical.

Sunil Gupta, Sunil with New York Review of Books, from Friends & Lovers: Coming Out in Montreal in the 1970s, 1975 (printed 2018), pigment print. Courtesy the artist; Hales Gallery, London and New York; Stephen Bulger Gallery, Toronto; and Vadehra Art Gallery, New Delhi. © Sunil Gupta. All rights reserved, DACS 2022.

Many of the photos have a genuine conviviality to them, and we are reminded that there is an art in relationships. The tenderness and warmth that pervade so many of the images draw us in, and it is easy to forget that we are spectators in a gallery and not acquaintances looking at moments of a shared personal history. Yet such feelings of fictive proximity, though enormously compelling, are unfair to Gupta the artist. Rather, “From Here to Eternity” is a testament to Gupta’s sharp critical intellect and novel forms of visual storytelling.

The default of photographic retrospectives embedded in place and time is to characterize them as documentary, records of lost worlds that some can still recognize and recall. Such bodies of visual records are vitally important, and if all Gupta ever did was take photos of himself, his family, his friends and the social worlds he inhabited, his retrospective would be of particular importance. Gupta, however, is not content to simply make a visual archive, however important such a record of diasporic queer reality is.

In his series “Toward an Indian Gay Image,” Gupta explores the presence of same-sex attraction and intimacy in India, at a time in the early 1980s where there was almost no representational vernacular of gay male subjectivity or public culture. In Gupta’s portrait Hauz Khas, named for the medieval building complex in Delhi, a man stands, back turned to the camera, the sunlight broken by an angled shadow cutting sharply from his right shoulder to his loafer-clad feet. Leaning contrapposto against the side of an ancient building, the man’s bright tangerine shirt and light pants provide vivid contrasts against the dark stone of the historic ruins. The man is both seen and hidden, referencing the reality of lived experience. A few feet away, at the bottom of the photograph, is a helmet for a scooter or a motorbike, a bit of protective gear for when the man turns back and has to immerse himself in a society of risk, restriction and the possibility of legal jeopardy. That legal jeopardy, a theme Gupta returns to in his work, is of course part of the colonial legacy in India, where the laws against homosexuality were imposed by the British and are an aspect of the imperial reckoning that Indian queers live with at home or in the diaspora.

Sunil Gupta, Anokhi, from Mr Malhotra’s Party, 2006 (printed 2009), pigment print. Courtesy the artist; Hales Gallery, London and New York; Stephen Bulger Gallery, Toronto; and Vadehra Art Gallery, New Delhi. © Sunil Gupta. All rights reserved, DACS 2022.

As a whole, the retrospective shows the ongoing dialogue and reflective meditation of Gupta’s artistic practice. It is at once personal and close to the body (his body, and the bodies of friends, family and lovers) but always embedded in contexts, contexts that not only shift in time and place but cross and intersect. Gupta and the array of people who populate his prodigious body of work are not isolated; indeed, Gupta’s work questions dichotomies of private and public, demonstrating the social, political and historical realities of lives lived.

One of the most striking sets of photographs is a series from which the retrospective takes its title “From Here to Eternity,” 1999. Here Gupta juxtaposes rundown, erotically charged venues, such as dive bars and sex clubs, with vulnerable self-portraits. He places himself under a shroud on a bed, takes a nude “selfie” in a mirror, captures himself naked turning away from the camera—flanked by a Christmas tree—a red rash visible across his back. The precarity of Gupta’s own health stands beside the increasingly neglected and disappearing sites of London’s queer nightlife. Both self and community were transformed by the HIV/AIDS pandemic, shifting sensibilities and the emergence of digital sexual platforms. Yet Gupta is not haunting these photographs; he is also living in them. In one, Gupta undergoes Pentamidine inhalation therapy to help prevent Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia infection in his lungs; in another, Gupta sits with a wry expression as he undergoes routine blood work. Gupta constantly points to the multiple realities, both mundane and iconic, of living with HIV.

In “Mr. Malhotra’s Party,” an ongoing series of photographs begun in 2006, Gupta revisits the context of Indian queer subjectivity that he had explored in the 1980s. Unlike those photos, with their ambiguity and stolen moments of intimacy, these large colour portraits offer a very different affect from the photos that composed exile. Gupta acknowledges that many of the prohibitions against homosexuality remain in place, yet he nonetheless captures a very different sensibility in which the strategies for community—the coded attendance at Mr Malhotra’s private party— illustrate new approaches, agency and confidence buttressed by the Internet’s fostering of alternative public spaces. In each of the portraits, Gupta’s subjects—young men and women in their 20s and 30s—demonstrate a belonging in their settings (parks, markets, city streets) that centres them in place. Arms crossed and akimbo, Gupta isn’t celebrating a diffusion of Western sensibility or progress but rather the work of Indian queers claiming spaces for themselves.

Gupta is not producing a set of simple visual dichotomies. Rather he reminds us of the diversity of experience of lives lived across borders, and these lives are lived and identities made in quotidian moments and both between and simultaneously within cultures. The post-colonial reality of those lives, shaped at the same time by belonging and displacement, is ever-present in the work. Gupta’s large, lush, later work, particularly the “New Pre-Raphaelites,” 2008, and his photographic storytelling in “Sun City,” 2010, provides a bold contrast with the early black and white images. Here we see possibility, creativity and the negotiation of culture and place. He utilizes the personal and the relational to construct a visual geography of intimacy, one that eschews normative centres and peripheries for one that is contingent, ambulatory and relational. In these relationships, there is possibility and power, be it an ethos of care, erotics or political consciousness. There is a clear-eyed hopefulness to the photographs, images that highlight strategies of living and creating. Critically informed, cognizant of the realities posed by illness, racism, aging and culture dissonance, Gupta’s work is a poetic affirmation and a genuine aesthetic triumph. ❚

“From Here to Eternity” was exhibited at Toronto Metropolitan University Image Centre, Toronto, from April 6, 2022, to August 6, 2022.

David S Churchill is a professor of history at the University of Manitoba, art writer, occasional curator and lover of flowers.