Subconscious City

In “Subconscious City,” the third in a series of exhibitions curated by artists Shawna Dempsey and Lorri Millan for the Winnipeg Art Gallery, a couple of things seem evident. A few truisms. Winnipeg has many excellent artists. I am happy to see and see again the photo-text work of William Eakin, the bronze character by Jordan Van Sewell, Jennifer Stillwell’s installations, Grace Nickel’s delicate and stunted tree forms, Eleanor Bond’s fine, messy mixed-media works on paper. We have a vibrant artist-run culture, with equal measures of skepticism and ambition. Lately, our once gritty margins have become something of a glittering centre. There are, it must be said, expectations. We have seen a dealer or two on the streets in February. Murmurs of collections swallowed whole by the American metropolis to the south are balanced by the image of the artist in her 50s, 60s or 70s, felled by precarity. There is something else, though, in this historic juncture: a deep-enough swath of a shared popular culture, not just of English watercolourists, or of pan-Canadian landscape schools, but a culture made by artists who have fought and battled with this place long enough to enact a renaming and to expect some shared reference points. One could point to the Maryland Hotel, 2006, as painter Krisjanis Kaktins-Gorsline has done. One could point to it, remove its moniker, challenge its husky shape, surround it by the emblems of painterly decay and, still, we would know it anywhere. It is ours.

David Wityk, BDI, 2007, digital photograph, 39 x 52 cm. All images courtesy The Winnipeg Art Gallery.

“Subconscious City” gathers together threads and layers. There are 27 artists in the exhibition, supported by others (poets, art historians, planners, filmmakers and public intellectuals) in the catalogue. I cannot name them all, can I? Gathered are a broad demographic from a few generations and many formations. It’s a brilliant facsimile of the diachronic and synchronic spread of the polis in miniature. In the catalogue, writer Sigrid Dahle lobs the curatorial premise into literal play. She asks conspiratorially, “Doesn’t free association, so valued by Freud, make for a marvelous research method?” Freud may be the foil for the curatorial theme (with the vexed prefixes sub, un and pre), but it is the city that is the social and spatialized arena for the distillation of contents, as much as it is the psyche. Critical French philosophers and sociologists Pierre Bourdieu, Michel de Certeau and Michel Foucault hover in the rooms as much as does 19th-century Vienna.

Let us take our place in the dream work, I mean the exhibition’s narrative. (I swear I can hear chortling coming out of the catalogue. It must be from Jeanne Randolph’s phantasmagorical text.) There are familiar locales: David Wityk’s Bridge Drive In and Diana Thorneycroft’s sardonic toy store heroes in front of the provincial legislature in Auditions for Eternal Youth. We could begin with the distant view. In the middle of the room, on a side wall, KC Adams has tamed Winnipeg’s sprawl in six bleached-out aerial maps called Circuit City. At the other end of the spectrum, the peeling paper on hoardings, photographed by Wityk, are constructed as colourful close-ups. The city is brought into focus as it is traversed. Lynda Pearce describes a relationship to the built environment in The Bell Hotel with felt marker sketches and diaristic excerpts. Acknowledgements are made of the extremes of Winnipeg’s breadth on the rivers, as in Robert Sim’s tiny oil Early Evening, St. Boniface, McMillan’s photograph Winnipeg Spring with its nuanced colour and Simon Hughes’s stylized ice drifts in River Saga. Present too is the banal and the idiosyncratic, made quirky in Sarah Crawley’s views of architectural anecdote, crumpled and scanned through Richard Dyck’s flatbed scanners, or insistently horizontal like the flat, flat prairie in Richard Holden’s delineated views of streets in the West End.

Scott Stephens, Down Main 1-8, 2007, digital photograph, 17 x 23 cm and 30 x 45.5 cm each.

The exhibition unfolds with the juxtapositions that one might find walking in the city. There is a certain wobbly randomness to the structure, an obstacle here, an aperçu of something that catches the eye there, a coloured wall that beckons, a noisy corner … or is that jake moore’s audio piece about Portage and Main? It’s the sound of contestation. The sound of voices overridden by bottom-line budgets. Winnipeg is a city of radicalized conflicts, uneven educational systems, urban core and rural urban fringe. Privilege and poverty. Freedom and incarcerations. The late poet Marvin Francis speaks this ground. He writes in My Urban Rez how “the violent, down-and-out ingredients formed my first impressions of this city environment.”

The two-tiered system of racialized justice is in evidence everywhere. It intersects with filmmaker Noam Gonick’s Precious Blood. Young adults mediate their emotional and sexual lives through cell phones, snippets of conversations, and glass and concrete structures. Lives and relationships are shot through by the state apparatus. Gonick’s storyed projection screen is a multiplex in miniature, deliberate and stylized. There are a lot of oil painters in this show, but more photographers, scanners, filmmakers and digitizers. Scott Stephens’s photographs of his friends and shops on Main Street stand out. The casual visibility of the subjects and locales in the yellowed light underscores the civic anxieties, fears and stereotypes about the neighbourhood. In a similar manner, Kristin Nelson’s 18 paintings, Telephone Booths, Winnipeg, consider the dispersal of power and its effects. The paintings have missing centres where the ghosted silhouette of a pay phone lies in absentia. Bonnie Marin’s sinister collages, Keith Berens’s brooding, textured oils and Rachel Tycoles’s industrial views of Weston in asphaultum and tar round out the moments of greater darkness. I stumble into the centrally installed Atelier National Super-8 Assignment with works by filmmakers Matthew Rankin and Walter Forsberg. They are on a mission to cure civic self-loathing. In the latter’s film, pulsating silkscreened images of Pop hero Burton Cummings redouble on the large screen. Cummings’s musical exhortations to “Stand Tall” are combined with cheesy effects, repetitions and implied action. You don’t need New York or Toronto when you have Burton.

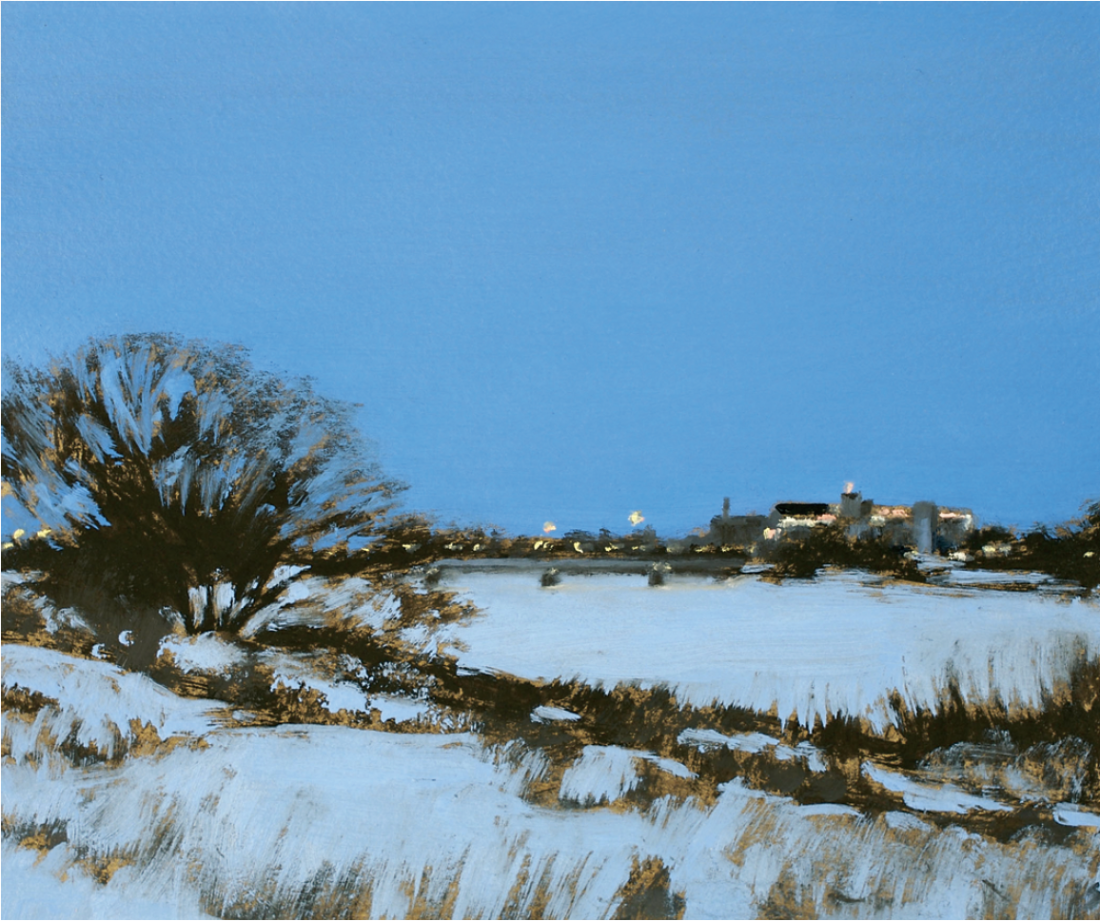

Robert Sim, Early Evening, St. Boniface, 2007, oil on paper, 16.5 x 19.8 cm. Collection of Kathy Pratt.

The best work in “Subconscious City” transforms our understanding of the local into moments of recognition, and transcendence. Leah Decter’s sculpture, Whole Cloth, of sheet lead, felted wool and fabric, is a work of monumental simplicity. It’s the scene stealer. The sculpture cascades from high on the wall to low on the floor and it metastasizes the notions of labour, river life, sweat and materiality with the geographic, economic and industrial figures of the city. It might have been a smaller show. Still, I might have added a Don Reichert and a Photoshopped image of the Redwood Bridge, or a mythic work from one of Wanda Koop’s city views. But, a popular show is a popular show is a popular show. Need I say it? Winnipeg has many excellent artists. ■

“Subconscious City,” curated by Shawna Dempsey and Lorri Millan, was exhibited at the Winnipeg Art Gallery from February 8 to May 11, 2008.

Amy Karlinsky writes, curates and teaches from Winnipeg.