Stoke Signals

If you were a regular gallery-goer and had wandered into the limestone-clad entrance to the Winnipeg Art Gallery’s Eckhardt Hall on the evening of November 18, you would have thought you had entered the wrong building. The space was packed with young people and the atmosphere was closer to a street carnival than a conventional gallery opening. In one corner there was a half-pipe on which 28 members of Winnipeg’s best skateboarding teams (from Red Riding, Green Apple, Sk8 Skates and The Edge Skatepark) took turns executing moves that looked both thrilling and hazardous. On the floor was a mural collaboratively designed by Peter Thomas, Mike Valcourt and Kenneth Lavallee, as well as a grind box replicating the shape of the WAG. Before the doors of the real gallery closed, some nine hundred people had attended the opening of “Boarder X,” an exhibition of seven Indigenous artists from across Canada whose art connects to the idea of moving fast on one kind of board or another. The audience was attentive and excited. In the language of skateboarding, they were stoked.

The exhibition and the events surrounding it was the idea of Jaimie Isaac, the curatorial resident of Indigenous and contemporary art at the WAG. Isaac, a Sagkeeng First Nation member of Anishnabe and British heritage, is among an accomplished group of contemporary Indigenous curators who are changing the way we view the relationship between art and the institutions in which it is shown. She brings to her position an admirable history of curating and critical writing, and in the context of “Boarder X” she can additionally claim some serious street cred. She is herself a skateboarder and over the course of her practice has broken her arm five times, her collarbone

Meghann O’Brien, Sky Blanket, 2014, woven mountain goat wool. Collection of the artist.

once, and scraped an entire side of her body. Today she admits to a degree of self-preservation since she has a young son, but her passion for board culture remains undiminished.

All the artists in “Boarder X” either have been or are practitioners of skateboarding, snowboarding or surfing, and each uses their art to make a connection to some aspect of landscape, whether environmental, social or political. Mark Igloliorte, an Inuit from the Nunatsiavut Territory of Labrador who now teaches at Emily Carr University, has been skateboarding since the early ’90s. His paintings and videos layer kayaking, his new passion, and skateboarding, his old obsession. In the grip job of My Yellow Aquanaut he places a yellow kayak on the black deck of his skateboard. It results in an elegant economy. Meghann O’Brien, who is Haida Kwakwaka’wakw and Irish, is a former competitive snowboarder and the only woman in the exhibition. She has found a way to link weaving with an augmented appreciation of British Columbia’s landscape; her Chilkat robe woven from mountain goat hair sets aside the traditional depiction of family lineages to render a set of dualities through both colour and gender. She also wove the cedar on the board of her collaborator, Mason Mashon, a Saddle Lake Cree, whose photograph of a mountain down which he is about to snowboard presents a whole new take on the idea of the sublime. The mixture of awe and terror owes more to torrid Edmund Burke than Torah Bright. There is, as well, a sense of awe in the epic painting by Roger Crait, a Cree from Winnipeg; Babble on Babylon, Babel on, a high-key, furious, apocalyptic oil and mixed-media painting from 2003, has lost none of its intensity. At the other end of the emotional spectrum are the documentaries of Steven Davies, a Coast Salish from Vancouver Island, whose films establish tributary links with elders in the communities where he works.

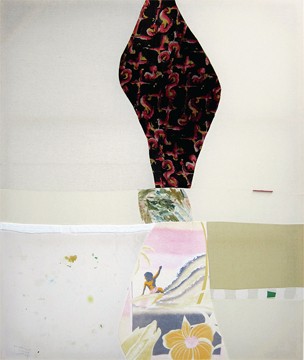

Les Ramsay, Goofy Foot, 2014, fabric collage, watercolour, oil paint. Collection of the artist.

The exhibition also includes work that plays with existing relationships between inherited values and new expressions. Les Ramsay, a Metis from Saskatchewan, is a formalist who uses craft and collage in his fabric paintings to organize a finely balanced sense of materiality. A sensitivity to material is the most obvious of Jordan Bennett’s many gifts; in his carved paintings on wood he brilliantly combines quillwork and pendant patterns from Mi’kmaq and Beothuk cultures in a reimagining of a lost, cooperative history. All seven artists are engaged in a process that Jaimie Isaac views as a mobilization of traditional knowledge. “I think through their individual practices, the artists are really making an inquiry about what can be considered contemporary.”

As part of a round table with the artists on the afternoon following the opening, Michael Langan gave a presentation about Colonialism Skateboards. Langan is from Cote First Nation around Kamsack, Saskatchewan, and he designs and sells skateboards with decks depicting images from the abusive legacy of colonialism—massive racks of buffalo skulls, the residential schools, and the “pass system,” in which Indigenous men were issued passes to leave their reserves only if they adhered to severe restrictions. His skateboards turn the negative history of colonialism into an opportunity for social education. During his presentation, Langan commented on how pleased he was to be invited to talk to students in schools throughout Saskatchewan about the meaning of his skateboard designs. Roger Crait’s response to his role was that he had become a member of the “Board of Education.” The remark was not only witty but true to the spirit of “Boarder X.” This important exhibition signals the need for a new kind of learning in which we are obliged to set aside our preconceptions and stereotypes about Indigenous culture, get on board, and go along for the ride. Get stoked, it could get gnarly. ❚

Jordan Bennett, Wo’kin, 2016, acrylic paint on carved yellow cedar, 28 inches diameter. Collection of the artist.