Stitching in Time

The Artful Life of Colleen Heslin

Today she is a painter who stitches her pictures together. But for many years, the artist Colleen Heslin was perhaps best known, around Vancouver art circles anyway, for her project space called the Crying Room. In 1999, Heslin took over the lease on a derelict, former retail unit in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside and for over a decade she put on semi-regular group shows there, until she left Vancouver in 2010 to complete an MFA at Concordia. A complete list of her exhibitions is available at <thecryingroom.org>, where many grainy images present most of the shows and a sense of the room. Working with absolutely no budget and word-of-mouth to generate interest, the Crying Room was a completely self-motivated curatorial project by an emerging artist studying at Emily Carr, intent on showing other emerging artists. Her generosity and the inclusive atmosphere of the Crying Room provided many young artists with their first shows. In most cities there is usually a gap of this kind that Heslin ably filled—a personal space generally open to the public that showed local emerging artists.

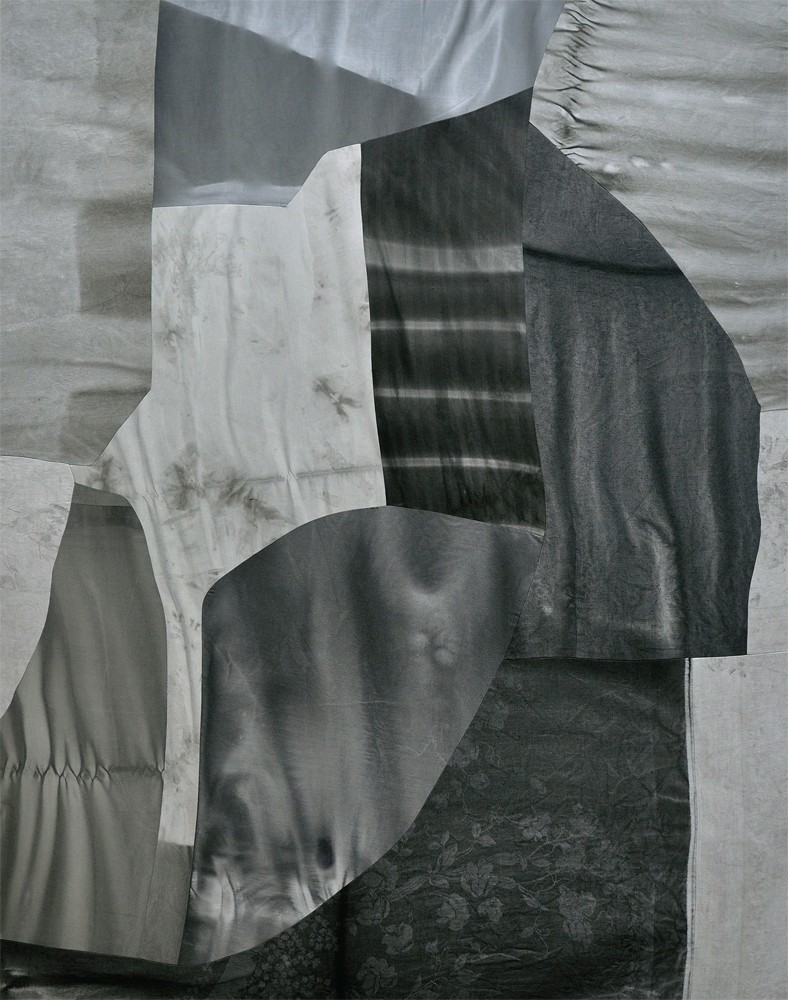

Walking and Falling, 2015, ink on cotton and linen, 60 x 48 inches. Courtesy the artist.

Its nondescript location on Cordova Street one door west of Main Street meant that an opening party for a new group exhibition at the Crying Room required paying a visit to the most tragic, drug-ravaged area of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Most of Heslin’s visitors came in September in a mob for the annual SWARM. Stan Douglas’s studio was an invisible neighbour. Jeff Wall’s studio was also on Cordova Street, a few blocks east. But from the start, Heslin’s Crying Room was the youthful open-door antithesis to the typical hermetic, private studio of a busy artist. And, out of creative necessity, the Crying Room offered a younger generation a place to respond to the dominance of photo-conceptualism in Vancouver’s art scene and its bias towards rarified, monumental work. The artists who showed at the Crying Room were unabashedly hand-held, low-budget, and intimate—making drawings, small paintings, sculptures and other conceptual miniatures. The show “Photographs From a Fan Boy’s Camera” featured Ryan Quast’s art-star stake-out pictures: Kodak 4 x 5-inch point-and-shoot paparazzi-style photos of Jeff Wall parking his car, Stan Douglas riding his bike, a pedestrian Rodney Graham and geomapping of all the photo locations. For many years I lived in the neighbourhood of Strathcona, just south of Jeff Wall’s studio and a 10-minute walk to the Crying Room. But because I was on the other side of Hastings Street, I still had to plan out a mental map of my walk to decide in advance where I thought it was going to be the least awful experience crossing Hastings Street. Example: I once saw a man walking dead down Hastings Street with his plaid shirt unbuttoned and an open wound in his stomach spitting blood. On a rain-slicked winter night, most of the area north of Hastings was a no-go. But the Crying Room was right there in the thick of it. No matter which path I chose, there was no avoiding Hastings, it had to be faced.

Vanessa Brown, Heavy Metal Flowers, 2013, spray paint on steel, The Crying Room, Vancouver. All images courtesy Colleen Heslin.

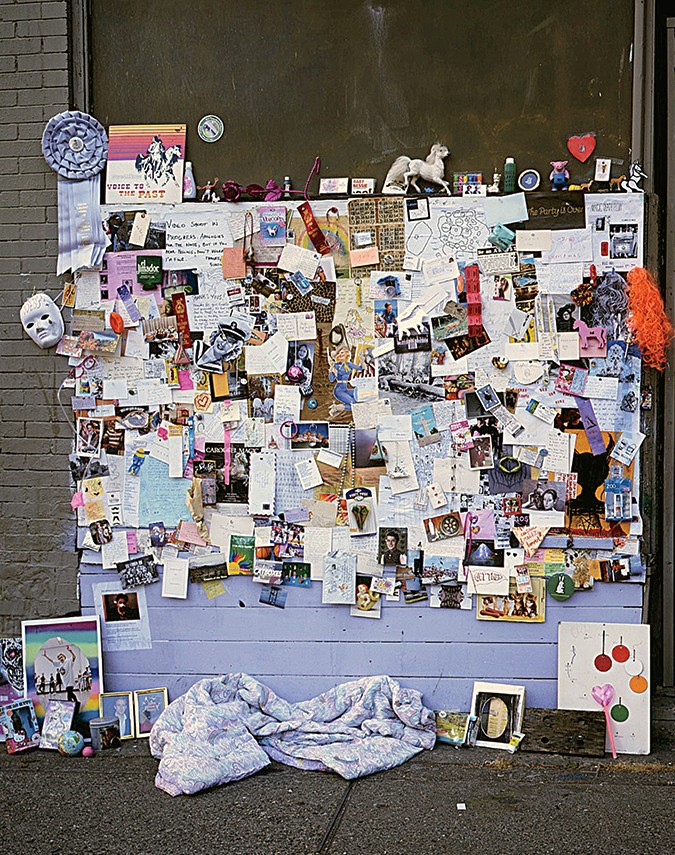

Jenn Jackson, Pony Board, 2014, The Crying Room.

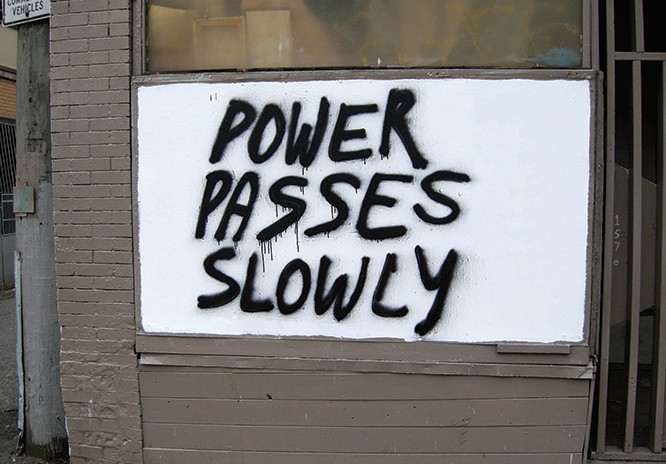

Olivia Dunbar, Power Passes Slowly, 2012, The Crying Room.

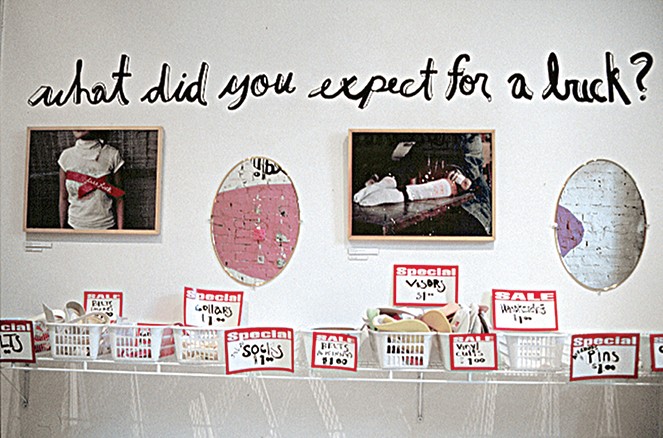

Elizabeth Zvonar, Free Luck, 2002, The Crying Room.

The Crying Room was not funded through any traditional arts granting councils; Heslin sold snacks and drinks out of her kitchen fridge at the openings and sometimes cooked more elaborate meals on her stove for guests who stayed late into the night. This lack of budget meant that for all intents and purposes the work on the walls was for sale. I doubt much emphasis was put on the mercantile side of the project. Heslin approached the curatorials as a social part of her art practice, using the space to foster a sense of community among a young era-wide variety of talented artists. No other gallery in Vancouver took as many chances. Forgoing furniture for art meant Heslin’s sleeping quarters consisted of a tiny wood bunk loft space perched over the gallery, accessible by ladder. For the longest time, Heslin had no proper neighbours except for the creepy strip club, the creepy convenience store next door, and the creepy diner on the corner across the street that was never open for regular customers anymore, now that it paid rent thanks to steady gigs starring in so many movies and television shows as a creepy diner. Then Solder & Sons, a used bookstore, opened up around the corner on Main Street and started serving strong espressos and freshly squeezed juices, where I would often bump into Heslin having her breakfast. Then I would follow her back to the Crying Room and see what was on the walls. Sometimes it was the work of other artists, and as the years went on the time between exhibitions stretched out and more often it was her own work-in-progress that was displayed. One memorable Crying Room show from 2003 featured Landscape No.2, an extra-wide strip of tanning-salon bronze latex meant to look like human skin. It was stretched out along the wall at least 10 feet and replete with long thick hairs, not to mention the ingrowns, the red, black and white pimples, and one extraordinarily swollen carbuncle. Repulsed, I was reminded of Woody Allen’s line about the chilly reaction book critics had to a novel entitled The Proud Emetic. (I had recently seen the same artist, Devon Gifford, appear on stage at the Western Front where she crouched over an amplified aluminum bucket and urinated, I kid you not, for no less than five minutes, I think as part of a fundraiser.) Gifford’s grotesque, brilliant feminist parody of flesh haunts me even now, 12 years later, with its revolting beauty and uncompromising wartiness. This organ without a body was spread out across the wall and even extended around the corner to affix to the inside of the Crying Room’s entrance door, so that whenever someone came in, the skin strip had to bend, like a joint in an arm or leg. Ew. Then, relief: …

…to read the rest of the article on Colleen Heslin, order a copy of Issue 134 now.

Installation view, Au Pair, 2014, ink and dye on cotton, 66 x 96 inches, Monte Clark Gallery, Vancouver.