Steven Leyden Cochrane

Inside Steven Leyden Cochrane’s “Walled Garden,” the air seemed thicker. Although Cochrane—a Florida native—now lives in Winnipeg, his work suggests that he continues to cultivate a tropical mental climate. His recent exhibition at the collectively-run Negative Space was overgrown with a profusion of work that returned to Cochrane’s Floridian youth: personal artifacts were intermingled with images of abundant plant life and retro courtyard architecture, ocean views and hurricane lamps.

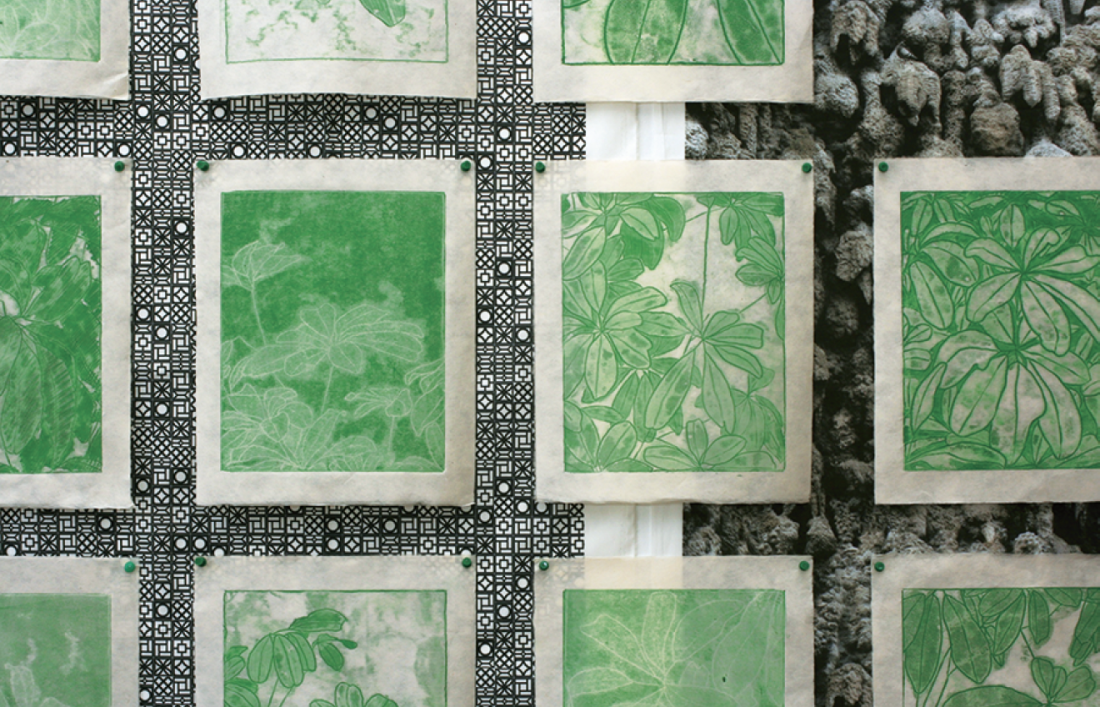

The idea of a walled garden structured the exhibition both formally and psychologically. Several groups of prints and drawings were displayed in grids over large swaths of coloured and custom-printed fabric, while photographs, mirrors, and other objects were clustered in corners. Cochrane’s layered installation strategies invite us not only to look at his work, but also to peer through it, suggesting that every view is partial and that what is hidden might be as interesting as what is seen. Untitled (Screen Wall) is a series of drawings of decorative concrete blocks—the kind you can imagine surrounding the backyard of a Tampa bungalow. Cochrane made the work by rubbing black encaustic over shaped wooden tiles, occasionally tearing the delicate mulberry paper in the process. With a backdrop of chartreuse and emerald green fabric, the tiny holes became beautiful jewel-like embellishments, turning the paper itself into a kind of screen wall.

Steven Leyden Cochrane, installation view “Walled Garden,” 2013. Photograph: Karen Asher.

The wall reappears throughout the exhibition, as motif and as metaphor. The concrete blocks of a screen wall are designed to create a sense of privacy without stopping the flow of air. It is tempting to think of Cochrane’s art practice as an analogously permeable structure, which permits us an intimate view of his personal Florida while also allowing a broad range of aesthetic influences (conceptual drawing, interior decorating, Cat Power’s Moon Pix) to blow through. Although diverse, these reference points are all clearly rooted in the particular experiences of Cochrane’s adolescence, giving the exhibition a compelling sense of place but raising the question of how much the work is really meant for us, as we look in from outside. But perhaps that’s part of the point of having a walled garden: to tease and tantalize those who don’t have access, to make them wonder about what’s really going on in the lives of friends and neighbours. It’s a way to hide and draw attention to yourself at the same time—much like making art.

Cochrane focuses on the twin desires for self-exposure and self-sublimation in I could still go there and I could still go there, 2012. These video loops show the artist trying to disappear into a tropical background in Photo Booth. (This is the same program your Facebook friends use to post warped one-eyed selfies; there is also a function that uses motion detection to map your face onto your choice of pre-loaded backdrops.) Cochrane subverts the program by failing to exit the frame while the software scans his surroundings. This means that so long as he stays completely still, Photo Booth thinks he is “background” and replaces him with a picture of tropical paradise—but every time he quivers or blinks, pixelated bits of face erupt onto the idyllic image. Paradise can only be restored if he returns exactly to his original position, a task which becomes increasingly challenging with time. By re-enacting the 2008 video four years later, Cochrane points to both the difficulty of resisting change, and the inevitability of repeating the past. The desire to escape himself is clearly stated: “I could still go there” is equally an expression of longing, and an anxious threat. Campy and not exactly subtle, the videos are also disarmingly touching. It’s hard not to ache at such a succinct portrayal of the desperate and debilitating self-consciousness of youth.

Steven Leyden Cochrane, Schefflera arboricola (Permanent green light), 2012–13, monoprints (oil on mulberry paper), 10 x 12 inches each. Photograph: Steven Leyden Cochrane.

It seems that Cochrane can’t stop himself from looking back, from trying to “go there” again and again. The presentness of the past is palpable in the looping repetitions of the walled garden; all living things, Cochrane reminds us, are relics of their lives. Frosted vinyl preserves Something I drew on the bathroom mirror ten years ago, while a gorgeous series of golden-brown drawings in toasted lemon juice depicts Plants drawn from memory with invisible ink. The oldest works in the exhibition predate Cochrane’s birth: two framed photographs of a lone and unremarkable buoy bobbing in Tampa Bay seem like they must have been captured in immediate succession, but in fact were taken by Cochrane’s grandparents on different days in 1947. Maybe they, like their grandson, also felt compelled to look and look again, to live and relive.

The deep melancholia of “Walled Garden” sets in slowly. At first, the bright, blooming colours and playful installation make the exhibition seem like a fun vacation, but gradually, almost imperceptibly, the climate changes. The exhibition casts the viewer as tourist, but it’s always hurricane season in this imaginary Florida: a fluorescent yellow stretch-velvet curtain tinged everything in the show with an ominous light. In this heavy, anxious air, visitors keep waiting for the storm to break.

Still, I’d go back again next year. Cochrane’s “Walled Garden” may be stuck in a tropical depression, but it’s lush and beautiful, and well worth the trip.

“Steven Leyden Cochrane: Walled Garden” was exhibited at Negative Space, Winnipeg, from June 14 to 21, 2013.

Erica Mendritzki is an artist and educator living in Winnipeg.