Stephen Foster and James Gillespie

Stephen Foster and James Gillespie come from divergent backgrounds. However, they converge in their interest in historical portrayals of the “other” in popular culture and the mass media. Both use media technology to examine structural aspects of representation and culture, subverting ideologies with reflexive tropes. Foster poses himself as both model and exemplar of the complexities of contemporary identity in video and digital photomontages, and Gillespie culls vintage print advertising for digital collages displayed in light boxes. In “Re-Mediations,” curated by Janet Jones, they offer distinct, yet related, reflections on how a dominant Eurocentric culture has marginalized and silenced other cultural paradigms.

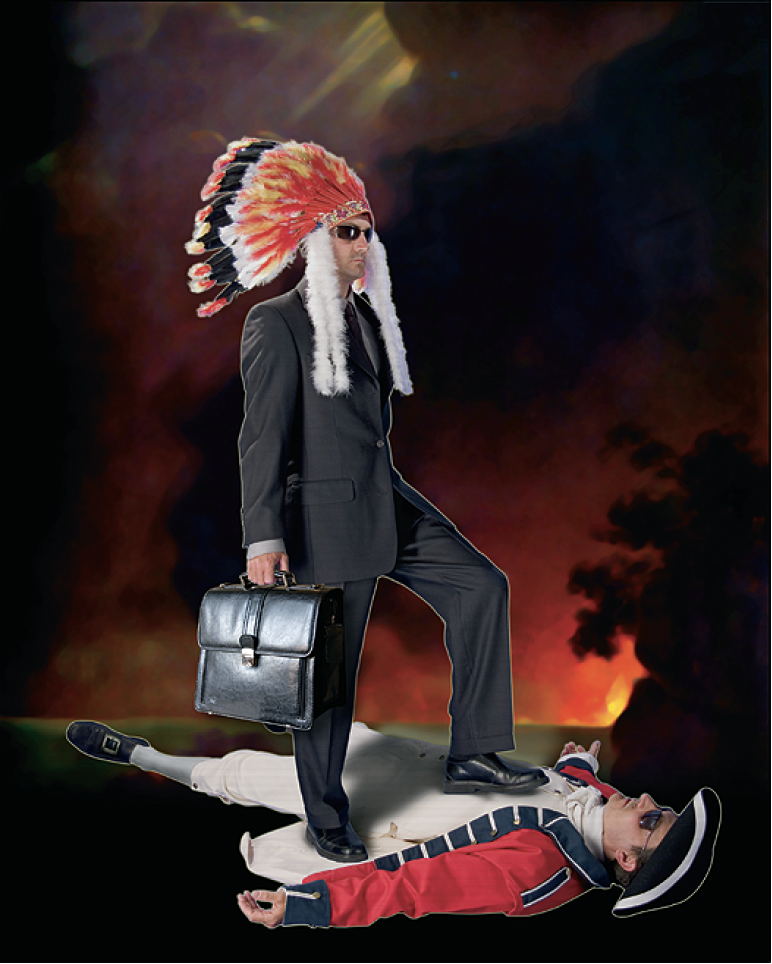

Foster, of Haida and European ancestry, focuses on portrayals of First Nations’ culture with multilayered references that include children’s toys, movie scenes and historic paintings. A recurring theme is the struggle between Aboriginal and European selves, which metaphorically reflect broader issues of contested nationhood. For instance, Foster poses himself in photomontages in both the role of “European” in mock conquest-era military garb, and “Indian” in feather headdress. He symbolically reverses the roles of victor and vanquished between these alter egos. In one work, his First Nations self places a foot on the chest of the European, who lies prone on the ground. Its partner piece features a role reversal, with the European in the dominant pose, encouraging consideration of continuing struggles over land, resources and self-government. Foster’s work is made accessibile by his humorous touch, created in part by the absurdity of the costumes. These challenge historicity by selectively blending cultural stereotypes from different eras within images that are intentionally conspicuous in their digital fabrication.

James Loran Gillespie, Sfumato, 2006, backlit Duratrans Lambda print, 31 x 25”. Photograph: the artist.

Another demonstration of Foster’s duality can be seen in a parody of the classic shootout scene presented in a looped, two-channel video installation projected on facing walls. On one side, Foster, wearing a cowboy hat, walks into the scene, draws a toy gun and fires. In the other projection, timed to run in alternating sequence, he wears a toy Indian mask and similarly enters and fires. Again there is no winner, just a continuous restaging of the same contest.

Gillespie, a Toronto-based artist of European descent, seeks to reveal the covert power relations in advertising produced in the capitalist euphoria after the Second World War. He often relies on visual juxtapositions, typically teaming these found images with personal photographs of barren lands encountered during travels in the Middle East and Asia, which presumably serve as an archetypal environment signifying “other.”

A succinct summary of Gillespie’s theoretical position can be found in Game. Here, he juxtaposes images of two white men in business suits playing chess while, in the distance behind them, fires burn in an arid landscape. To further emphasize the thesis, the entire image is veiled with mottled red spots. Another work situates an illustration of an applecheeked, all-American 1950s family on a View Master disc, flying over a desert, almost in magic-carpet style, accompanied by several military missiles. The work makes reference to an image’s power to exert control, to the commodification of travel and to the ways in which Western economic and military interests are interconnected in many parts of the developing world.

Stephen Foster, Death of Empire I, 2006, Lightjet Print on Enduratrans for light box, 36 x 60”

Gillespie, who has a doctorate in social and political thought from York University, engages with Debord’s conception of spectacle as a tool used by the ruling class to reinforce the existing social order. Yet the vintage imagery, which seems quaint and understated in light of today’s mass-media hyperbole, has a nostalgic quality that adds complexity to the reading. Depending on one’s age, politics and background, internalized notions of popular stereotypes about the idealized Leave It to Beaver life of “simpler” times can confront more claustrophobic realities of suburban homogeneity and the dire implications of a burgeoning consumer culture. For his part, Foster, a professor at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan, cites the influence of Hans Magnus Enzensberger’s critique of the mass media—“the consciousness industry” that can perpetuate injustices by persuading us to accept them.

Janet Jones, chair of the Department of Visual Arts at York University, who proposes “Re-Mediations” as a site to encourage dialogue on globalization and post-colonial issues, seeks to provoke in viewers a reaction to cultural and economic disparities as well as a deeper consideration of historical antecedents. “The media works of both of these artists are often overtly political and sometimes appear confrontational to the viewer,” Jones writes in the exhibition text. “But these provocative images reveal much about our current world, commonly including that an understanding of the past is crucial to our present.” Indeed, as Jones hopes, “Re-Mediations” effectively allows us to reconsider, from a personal perspective, our responses to issues of culture, geography and class. ■

“Re-Mediations: Stephen Foster and James Gillespie,” curated by Janet Jones, was exhibited at the Kelowna Art Gallery from September 16 to November 26, 2006, then at the McMaster Museum of Art from February 1 to March 31, 2007. The exhibition will travel to the Art Gallery of Southwestern Manitoba in 2008.

Portia Priegert is an artist and writer based in Kelowna, British Columbia. She is the director of the Alternator Gallery for Contemporary Art, an artist-run centre.