Stephen Andrews

What a ruckus we’ve caused. A reverberation builds with each image that is copied and shared online, and in their mass they produce a thunderous storm cloud of data. Every day over 1.5 billion new images are shared on the social media platforms Facebook, WhatsApp and Snapchat, and the vast majority of those are taken on the go with a handheld smartphone. While our contemporary relation to images in many ways resembles that of the second half of the last century, there has been a paradigmatic shift in the context in which those images are seen. Yes, we still recognize in ‘photographs’ the faces and bodies of our friends and loved ones, but for the past decade they have come accompanied by shards of the broken smartphone lens that snapped them up. Though the newest smartphones coming to market are equipped with cameras that rival those of your standard DSLR, the moment when the image revolution took hold, say 2001 to 2014, will be seen through the noise and confusion of a culture obsessed with making an image of everything, but an image that bares the trace of the shitty camera phone that captured it.

“Stephen Andrews POV” at the Art Gallery of Ontario is a testament to Andrews’s correct identification of this phenomenon over the past 15 years and sees the photographer interpret our contemporary imagistic mediation through the medium of paint. Exemplary of this is View from Above (2012), in which Andrews snaps a selfie with his phone while at a party 70-plus floors up at First Canadian Place in downtown Toronto. As if mirroring the luminous glazes that build up the canvas, reflected in the pane against which Andrews views himself are the lights of the street and the flash of a lens, obscuring his face and anonymizing his gaze. Specks which mark the absence of paint have become stars and the trace of the apparatus has become the focal point of the painting, pushing the instability of the image to the front, so much so that it might fall right out of the window. As images circulate, the artefacts they collect multiply with each transmission, and this is the noise that is depicted in “Stephen Andrews POV.”

Stephen Andrews, Entrance / Exit, 2014, oil on canvas, 243.8 x 182.9 cm. Image courtesy TD Bank Group and Art Gallery of Ontario.

At the heart of Andrews’s concern though is the question, how do these images reach us? They are infinitely mutable, constantly moving and transmittable at distances and speeds formerly unmeasurable. Their pixelated mobility disrupts standard binaries of local and global, public and private. And while Facebook, WhatsApp, and Snapchat run all these through algorithms to insure that each image meets the host’s decency standards (No dicks. No Butts.), guns are most certainly not excluded, nor is war. As if hand-in-hand, at the exact moment we saw our images disintegrate into a noise of data, America went to war in a faraway land, taking much of the rest of the world with it. One of the earliest works in “POV” takes its title from when the painting was begun, 10 IX 01 (2001), September 10, 2001, one day before we were plunged into this now decade-and-a-half long war on terror. The sound of war and the noise of the contemporary image share a common volume, relentlessly loud. As a means of coping with bedlam both close and distant, Andrews repetitively stamps a dot matrix of CMYK—cyan, magenta, yellow, key (black)—the standard printing hues, to compose an undulating wave of static that bewilders the eye as it searches to resolve a visage that cannot be found.

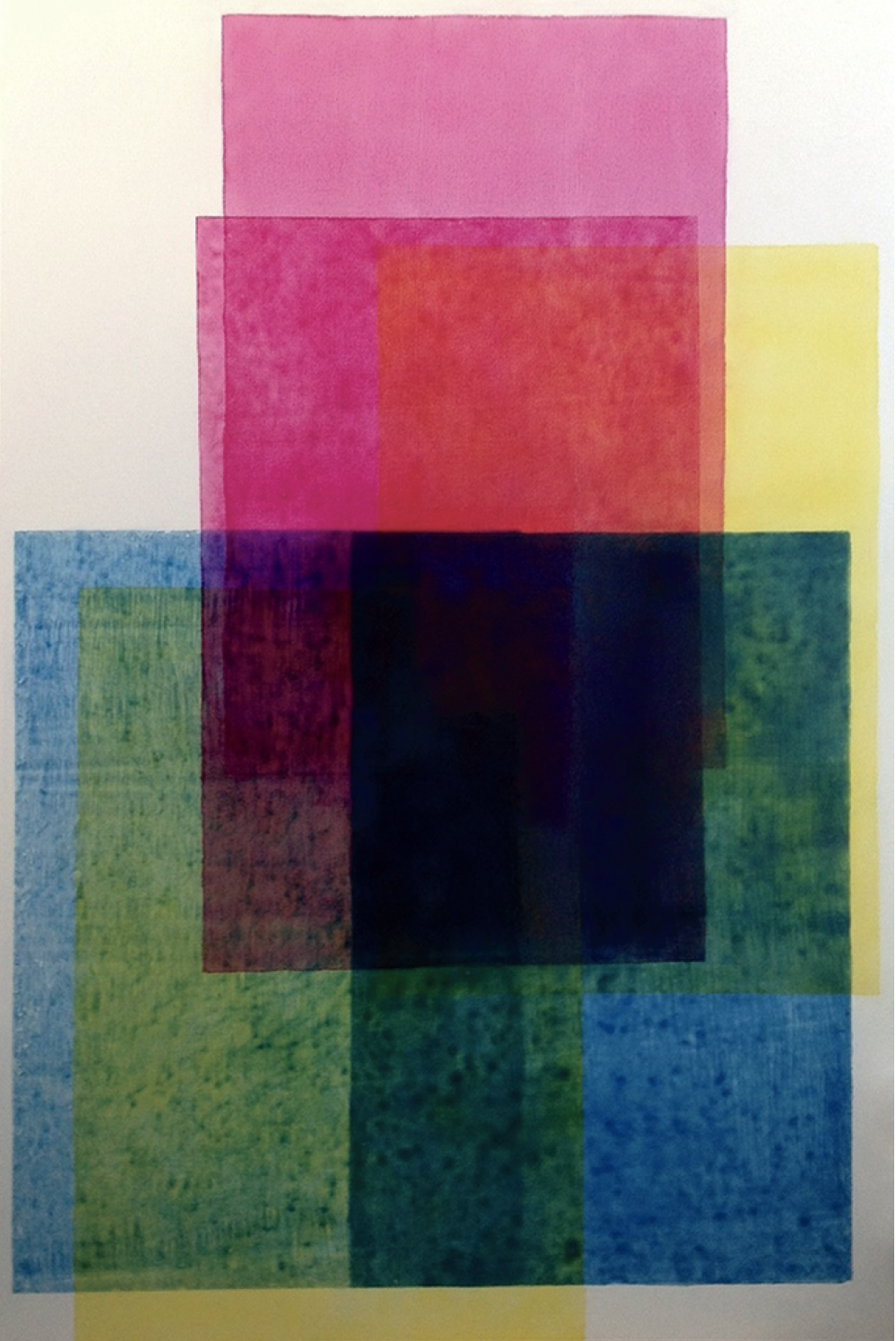

The instantly recognizable pattern of the CMYK print is a familiar refrain within “POV,” repeating throughout Andrews’s output of the last decade. In printing, these four colours are layered upon one another as a means of generating countless others, though in practice it’s thought that the less they are seen or heard the better. Andrews draws them to the fore and in their exaggeration they warp and bend before the eye, each image appearing and disappearing, coming into and then falling back out of focus. Towards the end of the exhibition in a room all alone hang a suite of Andrews’s newest paintings, “Butterfly Effect” (2014–15), that directly address the layering of colour and the accruing of data within the image. Each painting is comprised of large overlapping rectangular blocks of colour, again CMYK, created by painting large sheets of Mylar and laying them onto the canvas to transfer the paint. Both formally powerful and conceptually rich, the effect is emphatic, a distillation of the figures that have occupied Andrews with the printed image’s component parts.

Stephen Andrews, Butterfly Effect (figure b.), 2014–2015, oil on canvas, 9 x 6 feet. Image courtesy Paul Petro Contemporary Art, Toronto, and Art Gallery of Ontario. 54933p072t148.

Yet, the noise of Andrews’s images are at their most cacophonous in The View from Here (2009), a seven-metre wide study for a commission at Trump Tower, which shows “Toronto performing the myth of itself as a multicultural city” in the audience of a basketball game at the Air Canada Centre. Here too the crowd is anonymous, a camouflage of half-shaped bodies and faces out of focus. The thousands of undescribed eyeballs in The View from Here serve as a proxy for those images currently in circulation across the Internet. What must our images see when they stare back at us? Do we appear to them too fixed and immobile? Does our definition preclude the possibility of change? Perhaps then, this mutation of the image is less a product of humankind’s technological advances, but instead a potential speciation of the self, audibly led byour online twins, proposing a not-too-distant alternative, if noisy, future. ❚

“Stephen Andrews POV” was exhibited at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, from April 23 to August 30, 2015.

Aryen Hoekstra is an artist based in Toronto where he currently serves as the director of G Gallery.