Stephen Shore

“The Biographical Landscape” is a survey of Stephen Shore’s photography, presenting a timeline starting from his earliest B & W play to work revealing the conceptual genesis for what would become “American Surfaces” and “Uncommon Places,” two landmark series that helped push the medium’s formal capabilities. Throughout the exhibit, we see not only a biography of the artist but images made during a vital time within art photography’s own narrative.

Stephen Shore, US 97, South of Klamath falls, Oregon, July 21, 1973, C-print, 20 x 24”. Photographs courtesy Presentation House Gallery, Stephen Shore, and the Aperture Foundation.

Like many narratives, “The Biographical Landscape” gets off to an awkward start with Shore’s trying his hand at photo-conceptualism through serial propositions like self-portraits from eight compass points and clouds passing over a fixed space to mark time. These works are definitely of the late sixties— black and white, organic, rather dry and surprisingly minus text—but necessary in the trajectory of an emerging artist, paving the way for strategies like the seminal “Amarillo-Tall in Texas,” 1971, ten mass-produced postcards of the city’s civic and tourist attractions, each image’s where deliberately omitted on the back.

From here, he moves into 1972’s “American Surfaces,” which is a series of snapshots indistinguishable from your average tourist’s photos. In this series he documents the places, hotel rooms, people and greasy spoons he encountered on a solo road trip through the US. His first foray into the American landscape with a Rollei 35mm camera produced work of reasonable quality within the vernacular space of the 3-by-4 drugstore print, which couldn’t handle being printed any larger. These images stand apart from the rest of the exhibit—more immediate and gestural as a form of aesthetic inquiry, using the language of a banal means of production and prefacing the point-and-shoot aesthetic seen in contemporary photographs by Tillmans, Goldin and Araki. Unsurprisingly, the initial exhibit bombed, because the use of colour and the casual snapshot were seen as aesthetic no-no’s in the early ’70s, associated more with commercial applications and vacation slide shows than fine or conceptual art. Looking at them now, not to mention the parallel work of William Eggleston, it’s funny to think that they had to wait a couple of decades for entrenched aesthetic ideas about the credibility of the photographic image to catch up with them. Now that enough water has passed under the art-historical bridge, with the contemporary art establishment giving photography and now point-and-shoot its due, these images look strangely fresh, less distinguishable from a Terry Richardson or Jurgen Teller image in Purple or Artforum’s ad pages.

Stephen Shore, Room 316, Howard Johnson’s Battle Creek, Michigan, July 6, 1973, C-print, 20 x 24”

Dusting himself off and taking cues from critics such as MOMA photo curator John Szarkowski, Shore moved up in format to a 4-by- 5 and ultimately to an 8-by-10 view camera, and set off on more road trips throughout the ’70s to apply a different, more measured approach to the same subject matter. In turn, the results found in “Uncommon Places” were radically different. In these landmark images, the amount of content within the picture frame acts as an extension of Euclid’s maxim that “nothing that is seen is seen at once in its entirety.” Looking at the camera as an agent of time and the photograph as its product, the 35mm, and even 4-by-5, image is limited by its size in what it can show, while the formal qualities of the view camera (bulk, expense, tripod) require a more deliberate and precise approach, the trade-off allowing for more information to be recorded on a larger surface area. This density becomes a distillation of the act of seeing, and not merely looking, the punch provided by a surreal hyper-awareness within the frame. Shore’s large C-prints do not represent a captured moment, but an actual record of the 20-odd minutes it would take to set up the shot; everything refracted through the lens is funnelled into the click of the shutter and rendered in such detail that the prints invite the type of close study reserved for a Van Eyck painting. In “Uncommon Places” we see the difference between taking pictures, and making pictures where the images of houses and parking lots never appear to be more than what they actually are, due to the clarity of their surroundings.

Beyond any assumed objectivity or ennui (see: the Dusseldorf and Vancouver schools) in these images, we also see the dovetailing of Shore’s Pop and Conceptual influences, examining notions of reality within and outside the frame while alternating between fixed and nonlinear perspective. As a graduate of the Warhol Pop paradigm (he’s also well known for documenting the Factory during the sixties), he may have placed the emphasis in these pictures on the surfaces of a culture’s plain-Jane vernacular, miles away from the tinfoil walls and bustle of NYC. But his images of Terrace Bay, Ontario, or Great Barrington, MA, stand with a quiet dignity, no matter how dilapidated or mundane the little houses or intersections may appear. Rather than being (re)presented as “quaint” or “other” for urban “sophistoes,” he creates a quiet tribute to these common, yet quite uncommon, spaces that make up the fabric of North America. Shore may have intended to graft the trademark Warholian aloofness onto the places he passed through, but wound up making not only an unwitting homage to the unsung, but a body of work that was uniquely part of his own artistic trajectory, combining and then breaking away from the Pop art and conceptual vogues of the time.

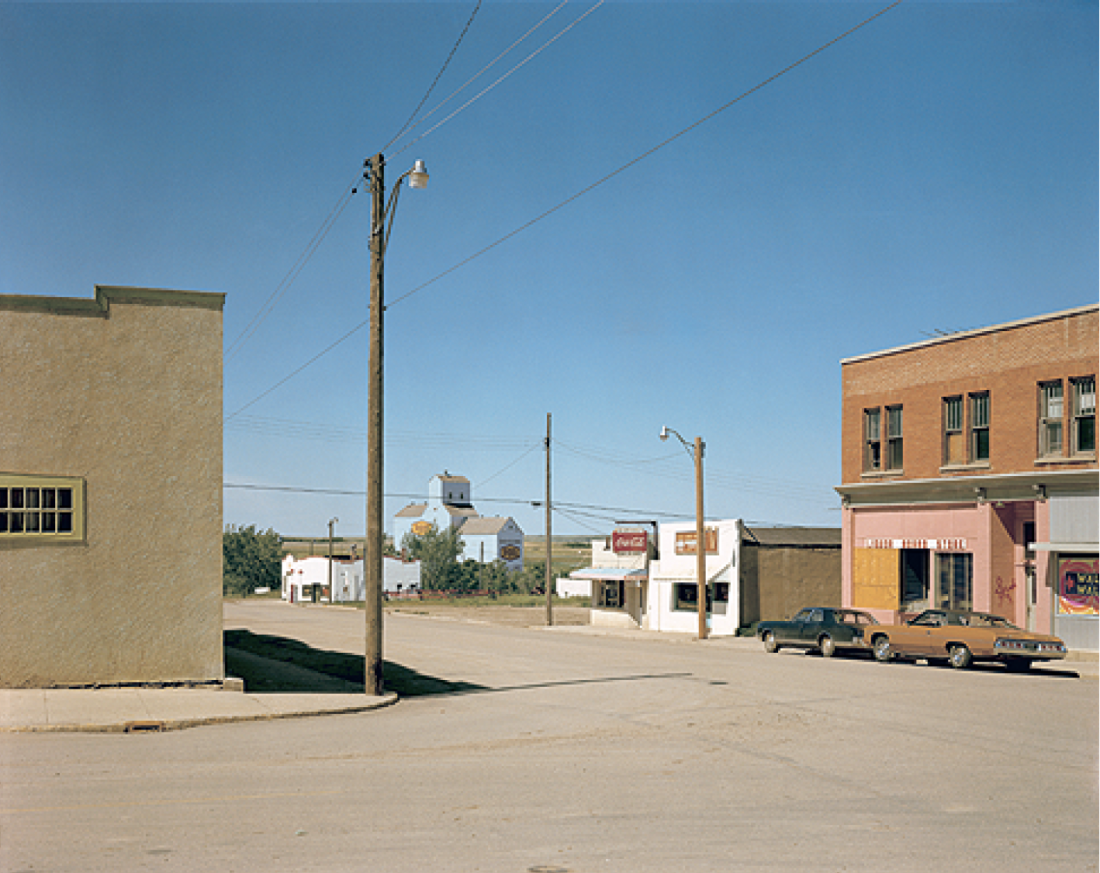

Stephen Shore, Main Street, Gull Lake, Saskatchewan, August 18, 1974, C-print, 20 x 24”.

Because the content is not suffocated by theoretical considerations, there is a remarkable warmth in the work, despite an initial austerity. These spaces are not at such a remove that you find yourself unable to relate to the works. He is documenting the mythological America and occasionally Canada (look for the grain elevators in the background), through the equally mythopoetic rite of the road trip, in deadpan images of what we usually ignore: the parking lots, motels and nondescript Main Streets of Anywheresville, the liminal spaces between the major urban centres and the tourist traps. Similar to his “Amarillo” work, these act as postcards from the mundane; any indictment of grand narratives or semiotic dissection are left up to the viewer.

By taking on the simultaneous roles of Tourist behind the wheel and Artist riding shotgun, we also see a document of spaces that have more than likely disappeared by now, a photographic Easy Rider showing a pastoral North America on the crest and spray of Modernism, the architecture and aesthetics giving way to its eventual Wal-mart-ization. Conversely, if you’ve taken a Greyhound bus trip across the country, you’ll notice that many small whistle-stop towns haven’t really changed much, except for different boards covering the same absent windows, like in his image of Main Street in Gull Lake, Saskatchewan.

It’s an evocative and nostalgic world that is on view, some 20 to 30 years later, if only for the makes and models of cars pictured (his Valiant seems to keep popping up in a lot of them). As clinical as the work may appear, Shore retains his thesis that his photography is always biographical—so the earliest to most recent work may not just be a record of the artist’s own movements through the landscape, but the viewer’s as well. ■

Stephen Shore’s “The Biographical Landscape” exhibited at the Presentation House Gallery in North Vancouver, British Columbia, from November 12, 2005, to January 15, 2006.

Christopher Olson is working, writing and studying at ECIAD in Vancouver.