Spiriting the Seen and the Imagined

In some ways, it was déja vu all over again. “Otto Rogers: Survey 1974-1993,” at Canadian Art Galleries in Calgary, was an uneven trip back into recent Canadian art that at first looking seemed to have very little to put it into forward gear. Instead of a curated overview of 20 years, as its title suggested, the survey turned out to be a selection from the inventories of three of Rogers’s past and present dealers. The newest of the paintings on view were two watercolours from 1991 and 1992. The 1970s were represented by just a handful of works. These included Dancing Elements (1979), a beautiful painted-paper collage, that provided an interesting segue into the 1980s. Pride of place went to these years, the decade in which 12 of the 23 works in the show were concentrated. As it turned out, this was a very good thing. It brought Rogers’s career into clearer focus from a distance, or perhaps I should say: from across a gap opened by the ten years during which he all but dropped out of sight of the Canadian art world.

Rogers was a well-known abstract painter in his early 50s, based in Saskatoon, when he left Canada in 1988 and went to Haifa, Israel, to take up a high administrative position in the Baha’i faith. He had been a devotee since 1960, not long after a Baha’i acquaintance pointed out that his paintings resembled prayers or supplications, and Rogers felt a life-changing shock of recognition. The principal tenets of the Baha’i religion, founded by Baha’ Ullah in Iran in the mid-19th century and headquartered in Haifa, are the essential unity of all religions and the unity of all humanity. When Rogers writes about his work it is always a professing of his commitment that art is worship. Rogers served two terms in the Baha’i administration in Haifa. He returned to Canada last fall, resettling in the countryside near Peterborough, Ontario, an area that has attracted other artists in recent years. The Canadian Art Galleries show and an exhibition of recent work held last year at Buschlen Mowatt Gallery in Vancouver have served to reintroduce him to the art scene here. Now is a good time to take a fresh look at his work.

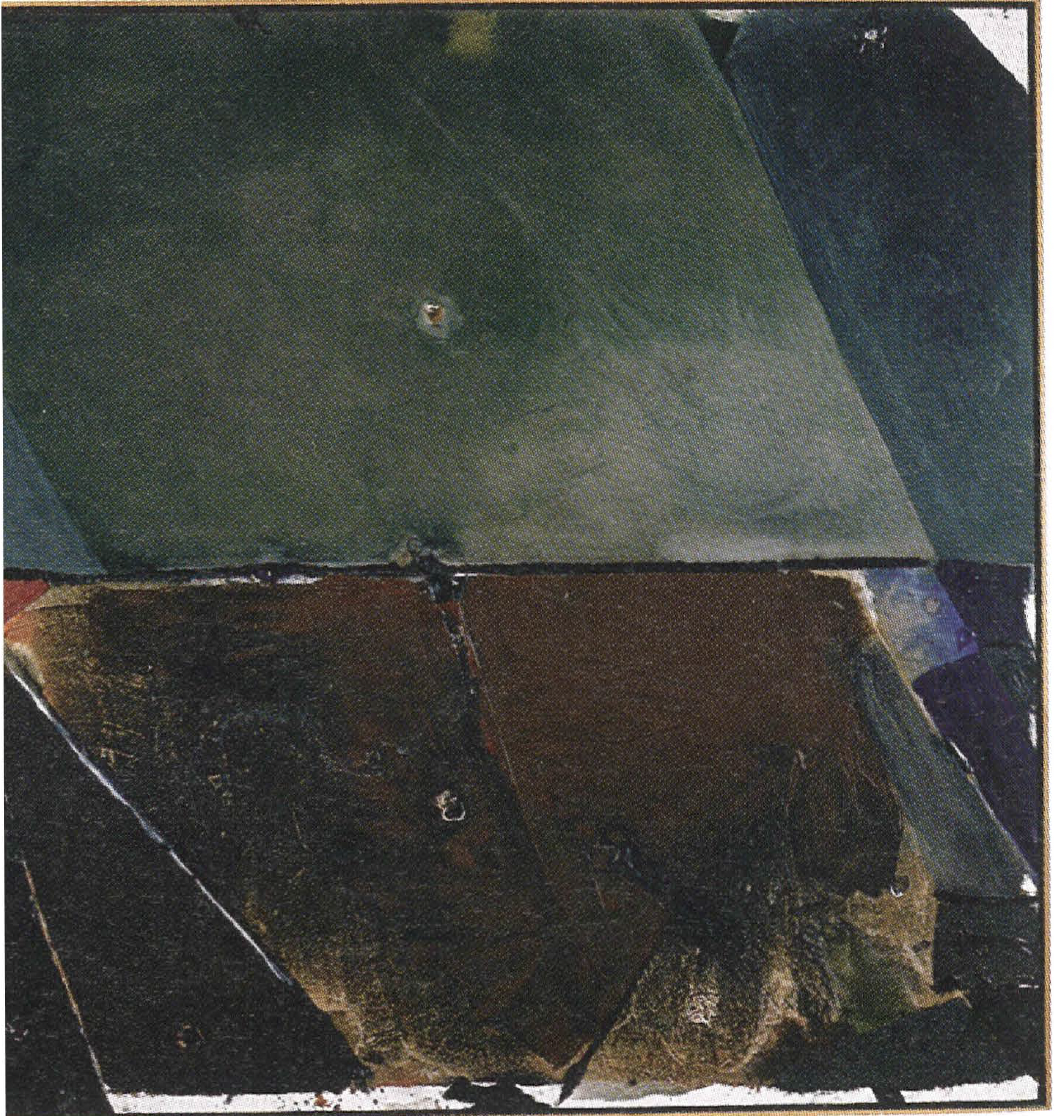

Otto Rogers, Untitled, 1982, acrylic on canvas, 60 x 60”. Photograph Josi Chu. Courtesy Canadian Art Galleries, Calgary.

There is an affinity to Paul Klee in a number of the 1980s pictures in the CAG show, especially Untitled (1982), Hope Island 2 (1983) and The Order of Feeling (1988). That Rogers’s goals have always been different from those of other abstractionists working on the prairies was also driven home by the opportunity to see him in relation to the Regina Five, whose work was showing concurrently at several Calgary galleries. Although Rogers has cleaved to the modernist tenets of keeping the painting flat and its surface in tension, his equal loyalty to content determined that he was never a member of the formalist camp. What he shared with Klee was a use of the abstracted landscape, the underlying grid, the suspended geometry, the animating diagonals—present as lines, planes of colour or wedges—and the surface that emits light not just as formal elements but as a vocabulary for expressing the spiritual. Moreover, this shared vocabulary suggests that Rogers’s work has been interpreted too narrowly because of his prairie origins and his allegiance to Baha’ Ullah, as though it were not possible to see the forest for the trees.

The forest, in this case, is the grove of spiritual abstraction, which had played an important role in modernism even before the publication of Wassily Kandinsky’s Concerning the Spiritual in Art in 1910. Despite their differing styles, the artists who fit into its congregation—as seemingly far apart as Mondrian, Lawren Harris and Richard Pousette-Dart—all have been inspired by the desire to transcend the visible. In the catalogue of the exhibition, The Spiritual in Art: Abstract painting 1890-1985, Maurice Tuchman identifies their shared impetus. “The five underlying impulses within the spiritual-abstract nexus—cosmic imagery, vibration, synesthesia, duality, sacred geometry—are in fact five structures that refer to underlying modes of thought.” These, he goes on to write, were common to a wide variety of artists, writers and thinkers. All five impulses are present in Rogers’s work; that he comes to them through the writings of both Kandinsky and Baha’ Ullah, but focuses primarily on the latter, should not cloud his artistic kinship.

Rogers seems intent on shifting how he is seen away from “prairie painter,” as he was widely known before his departure, and towards a broader context of spiritual abstraction. Perhaps we should have been paying closer attention to his writings all along. When Rogers aligns himself with other artists, it is to Kandinsky and fellow Baha’is’ ceramist Bernard Leach and painter Mark Tobey. For Rogers, the landscape is a “perfect” metaphor for his cosmic imagery, an other-worldly space divided into the duality of sky and land. “My use of the landscape was always indirect,” he wrote in 1991, “first establishing the most obvious features, commonly understood, and then quickly moving to a philosophic engagement with light and the horizon line, the symbolic demarcation which separates what can be seen from what can be imagined.”

For an artist, however, what can be imagined can also be coloured by other art, just as Rogers’s paintings in the CAG show suggested by their colour and composition; he has looked closely not just at Klee but also at Mark Rothko. Although Rogers’s work will undoubtedly remain true to its spiritual course, it will be interesting to see how its formal expression might be influenced by his return to Canada and residence in Ontario. ♦

“Otto Rogers: Survey 1974-1993” was at Canadian Art Galleries in Calgary from January 16 to March 6, 1999.

Nancy Tousley is a critic and curator who lives in Calgary.