Specific Prescence

Celia Paul and the Art of Painting and Writing

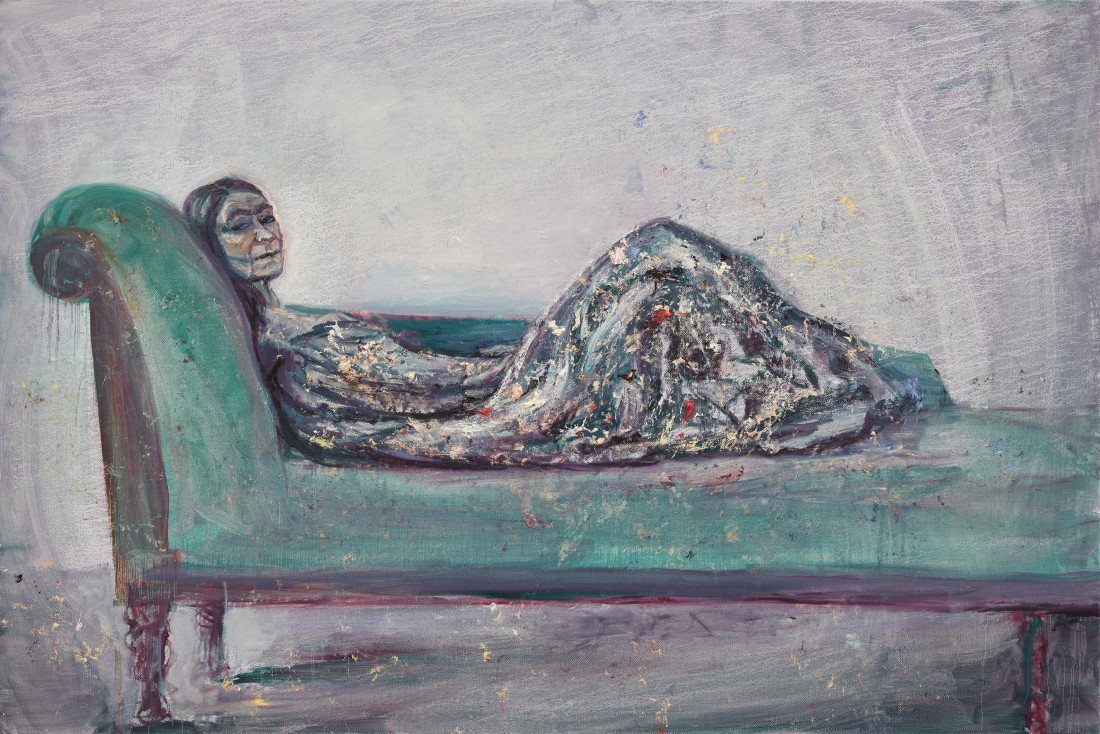

Celia Paul, Reclining Painter, 2023, oil on canvas, 121.9 × 182.9 centimetres. All images © Celia Paul. All images courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro, London.

In the following interview, Celia Paul straightforwardly explains how she decides what to include when she writes: “My scrutiny selects what matters to me.” In this context, “scrutiny” is the most apposite word she could have chosen. It follows that what goes for writing applies equally for painting—the tendency towards critical observation that “scrutiny” addresses. Paul chooses words with the same attention she brings to her visual art, so when she says that what she is after in her painting and drawing is a “specific presence,” she is, as always, true to her words. When painted, Paul’s subjects are utterly present, a condition that comes out of their intense specificity. It is not likeness that she achieves but presence. It is a presence in two registers: theirs and hers. “When I’m painting a person, I’m focusing entirely on them,” she explains, “I’m never looking at the brush marks I make.” She doesn’t look at what she has made, only at who she is making.

Paul is after a quite particular kind of attention in her regard for art. “To regard” has a congenial double meaning; it carries a sense of caring for—to have regard—as well as a requirement to look at—not to have regard but to regard. The word, both verb and noun, acts and is acted upon. The regard Paul has for her subjects is everywhere apparent in her painting: in the group portraits of her sisters seen through comfort and mourning; in the various compassionate portraits of her mother; in the evanescent paintings of her husband, Steven Kupfer; in the silent dignity of the single chair in her studio.

And what are we to make of the self-portraits, her ongoing record of relentless self-scrutiny? Her most recent capture of self is called Painter at Home, 2023, and is a testament to presence. It reprises the pose and dress of Painter and Model, 2012, a work from 13 years ago, but it presents a very different person. The new self-portrait has reached an apogee; the woman looks out more than she is looked at. Her embodiment of calm acceptance is the “home” alluded to in her naming. It is not a physical place but a psychic space and its self-reliance is total and uncompromising. Painter at Home is among her finest and most telling paintings. In a way that I can’t explain, it seems to be a religious painting. In praising Gwen John, Paul wrote that “she put the spiritual quality of art at the centre.” The praise that she ascribes to John is the same quality she inscribes at the centre of her found home. Another double—the painter gives praise and in the act of painting, the painter prays.

Paul remarks on the necessity of vulnerability, the Janus-face that looks to both subject and painter. In a small, 10 x 12-inch, oil on canvas called Lucian and Me, 2019, she paints an image of exquisite tenderness and vulnerability. She has long been aware of the sense of loss and separation that can exist between two people. “This feeling of separation from one’s beloved is tragic,” she says, “and trying to capture someone you love in painting is just an attempt to bridge that gap.” Lucian and Me gets as close as any painting she has ever made at repairing the tragedy of separation. Its depiction of love is heartbreaking.

I would be amiss were I not to say something about her writing. She credits Hilton Als for its genesis, but once she starts, she advances her own testament. “I wanted to make a whole art form out of my life,” she says in describing the purpose of her memoir, Self-Portrait. No one who has read it and the book that followed, Letters to Gwen John, her combination of diary, cultural history and art criticism, all gathered in epistolary form, can be unaffected by the book’s candour, humour and intelligence. It is worth pointing out that the “Diary” segment she contributed to the September 12, 2024, edition of the London Review of Books includes exacting and revelatory art criticism on Lucian Freud. Her ability to connect the amatory and painterly in chronicling Freud’s lost-and-found love affairs is rich and penetrating. Like all her writing, it is courageous and insightful in equal measure.

In March of 2025 she will open an exhibition of new work at Victoria Miro in London. The show’s irresistible title, “Colony of Ghosts,” is named after a 1963 John Deakin photograph taken in Wheeler’s restaurant in Soho. In the photo, a group of male painters are engaged in what appears to be a raucous, champagne-fuelled lunch. Among the painters are Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, Frank Auerbach and Michael Andrews. Her response to their exclusive camaraderie is a painting of dazzling self-possession in which she establishes herself as a club with one member. In Reclining Painter, 2023, she looks out at the viewer, her face an image of confidence that is almost dismissive. She wears her signature garment of many colours, but it is less a piece of clothing than a topography, like a small mountain of paint. The chaise longue on which she reclines, for an artist who normally surrounds herself with as little as possible, touches on the extravagant. It is tealy and paint-marked, but it is gorgeous, and the lines on her face have absorbed its colour and texture. She has become her painting.

“I want everything I do to be necessary,” she declares in our conversation. By her own measure, she is once again true to her desire. Celia Paul continues to prove she is the most necessary painter of her generation.

The following interview was recorded by phone to London, England, on October 17, 2024. “Celia Paul: Colony of Ghosts” will be on exhibition at the Victoria Miro Gallery from March 14 to April 17, 2025. Coinciding with the exhibition is the release of a new monograph published by MACK that covers 50 years of the artist’s work.

Painter and Model, 2012, oil on canvas, 137.2 × 76.2 centimetres. Photo: Stephen White & Co.

BORDER CROSSINGS: I’m going to read the opening three sentences of your splendid Self-Portrait: “I’m not a portrait painter. If I’m anything, I’ve always been an autobiographer and a chronicler of my life and family. I’ve told my life in images.” I admire those three sentences for their clarity, but am I to take from them that I can understand your life if I look closely at the images you’ve made about it?

CELIA PAUL: Well, you can’t tell everything. I’ve often thought about how fascinating it would be to get into the thoughts of painters because thoughts drift into your mind when you paint, and those things aren’t captured. But my painting is very closely autobiographical and I can only work on subjects that mean a lot to me. And those subjects change during a lifetime. I’m preoccupied by one thing or one person and then something else or someone else becomes the central thing. So in that way, you can follow the journey of my life.

So it was a conscious choice to paint only those people you were close to, and in no way did you see that as a limitation?

Absolutely not. In fact, the opposite. When I work from people I don’t know well—and I have done that—I’m much more literal in my representation because I’m not familiar with how they look. So the distance between their eyes and between the nose and mouth becomes something more important, whereas if I know somebody really well I have free rein to interpret them in my own way.

I first thought about your work through the lens of portraiture, a frame that we associate with ideas around resemblance and likeness. Are they qualities you’re after?

No, that’s not my priority. What I want is to create a specific presence. I want my portraits, and I think you can call them portraits, to be specific but not limited to a physical representation of what they actually look like.

That’s what you call getting to the truth. I wonder if that truth is phenomenological, that is, a truth to perception, or does it also have a psychological dimension? I’m trying to get a fuller sense about the nature of truthfulness in portraiture.

Well, each individual has such a very specific presence and the way they affect even the air around them is different. People have different energies. And without being too mystical about it, they do affect the air waves around them. I’m interested in the energy that each person has. I, myself, have always had this stillness in me and it’s not to do with not being an anxious person because I am an anxious person. It’s just my physical way of being is very still, whereas some people have an inner restlessness and that’s something interesting that I would like to convey about them.

Do you want to give me a better sense about the weight of the mystical in your art?

Well, I was born into a religious family and that whole discipline of prayer has entered into my discipline of painting. It’s to do with the ritual, the discipline of working every day, giving myself up and letting something take me over. And that is a mystical experience. In that way, I try to avoid consciously planning a painting. When I’m painting a person, I’m focusing entirely on them; I’m never looking at the brush marks I make. It’s only when they’ve left my studio that I put the canvas at a distance to see what I’ve done. Only then can I actually make any conscious critical judgment. And complete attention is not just using a measuring stick to see distances and proportions; it’s something else. I feel I can only get the real truth about what I’m seeing if I don’t think about myself and my process at all.

British Museum and Plane Tree Branches, 2020, oil on canvas, 63.5 × 55.9 centimetres. Photo: Benjamin Westoby.

I’ve seen videos of you painting and you seem to have a very light and lyric touch. You extend the brush almost as if it were a conductor’s baton. I thought about music as much as image making. Is that close to what you feel when you’re actually making a painting?

You’re right. I think when I’m working my energy stems from my stomach area and works up through my arm. And I do notice that when I’m painting a person from life, I hold the brush with my hand stretched out so that the energy flows through my arm, through my hand and onto the painting. But when I’m working by myself, not from life, when I’m creating up images, which I’ve been doing more and more, I paint in a very different way. I hardly use a brush at all. I use sponges or rags and rub in the paint. I’m much closer to the canvas, though I always have to work vertically. Working from life is risky in a way that working by myself isn’t. There’s an element of performance in it inevitably, even though I work in silence when I work from people. It feels sometimes as though we’re hardly aware of each other’s presence, me and my sitter. But I know they’re aware of me even though they may be in their own worlds. And that creates a performative quality in the experience, which isn’t there at all when I’m just by myself. I have no idea really what I do or how I might appear when I’m working by myself.

You say you have to give yourself up in order for anything to happen. Is there a conscious way to encourage that giving up, or is it something that happens in the process of painting itself?

It happens in the process of painting. I’m not sure whether I believe in God or not, but I do ask for help every second of the way when I’m painting. I don’t know who or what I’m asking for, but I know that it doesn’t come from me.

You refer to painting as “a crisis” and because of that you need help. It raises the question of who’s answering the crisis call. You are a reader of St John of the Cross, the 16th-century Spanish mystic, who is famous for the “Dark Night of the Soul.” The poem says that the night unites the lover with his beloved but not before they undergo suffering and trials, and it’s only through that experience that the state of perfection St John of the Cross is moving towards can be attained. Is there something about the dark journey that resonated with you?

Certainly, St John of the Cross is important to me, and I have and do experience that “dark night of the soul.” It’s quite difficult to put into words because I feel like I’m rather brimming over with too much. I’ve had quite a load on my shoulders these last years, so I’m hoping I’m seeing the light at the end of the tunnel now. But I do think it is probably the only way of getting rid of any smugness or self-assurance. I think you need to feel confident. In some way you’ve got to hold on to this feeling of yourself as being worth something because otherwise you lose everything. What’s at stake in this question of losing everything is not a total dispersion of who you truly, innately are. The “dark night of the soul” doesn’t require a complete demolition of self; it’s just a question of shedding all the false self-belief, the things that prop you up. There’s this wonderful passage by St John of the Cross that is quoted by Thomas Merton in one of his books about contemplation where he says you must allow God to take you by the hand as though you were blind and to lead you just trusting in that hand holding. I love that idea of complete trust in something else and being led not by one’s own sense of purpose or intention.

Is light part of the way that one escapes the dark night of the soul? You have written that depression “sinks through me like a stone,” and when that happens “the light begins to fail.” And you have written about the perfect light in your studio. Can the lightness get rid of the dark obliterating clouds that you have dealt with in your life?

Well, light is tremendously important and lightness as well. I want to struggle against the heaviness that was in my earlier work, which was important and gave it that particular quality, but if I’d not struggled towards a lightening, both in spirit and actual lightness of palette, it could have buried me alive. To get into darkness is a self-indulgence. I think it’s important to actually aim towards lightness rather than self-flagellation and darkness.

It sounds as if there is a radical rigour involved in what you do.

Well, I hope that’s the case with me. I would hate it to be the opposite. I want everything I do to matter. I don’t mean in a worldly sense, but I want what I do to be necessary to what I want to say. In that way, it is rigorous. I don’t want to paint anything just for the sake of looking busy, or saying how many hours I’ve done today, or anything like that. I need to be sure that it’s something I want to express.

…to continue reading the interview with Celia Paul, order a copy of Issue 166 here, or subscribe today.