Sophie Calle

It is all about the women. It is the women who have us. They hold and transfix us, even when they refuse to meet our gaze. Scores of women: an actress, a psychoanalyst, a student, a judge, a clairvoyant, an intelligence agent, a dancer, a semiotician, a mime artist, a Japanese opera singer, and on and on in extensia. It is they who guide us through the porous and moody labyrinth of Sophie Calle’s wonderful “Prenez soin de vous (Take care of yourself),” a monumental installation at DHC/ART.

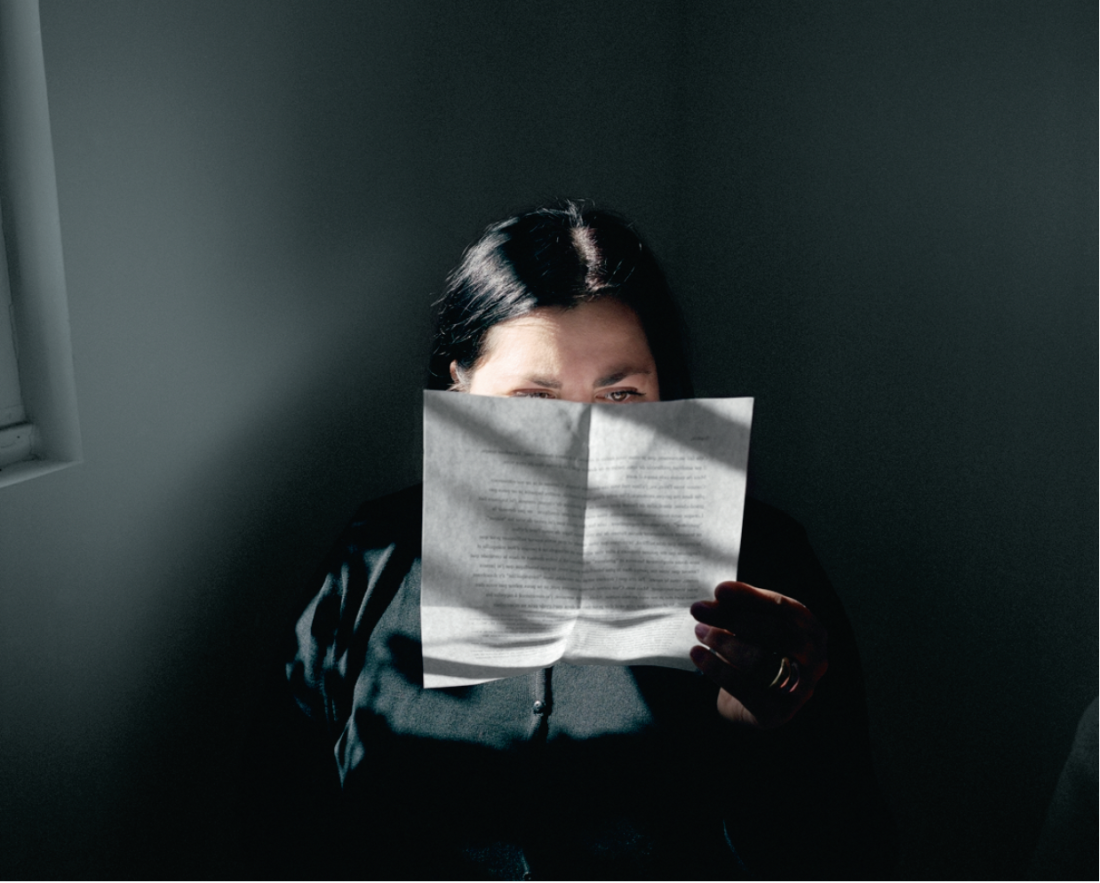

Some of these women’s faces are not to be seen—as though they had insisted upon visual anonymity. The panoply is arresting by virtue of its very diversity— and by the fact that all these women demonstrate an intensity of attention and care to the project at hand: that most ubiquitous of things, an e-mail, the hard copy of which many are seen reading.

All these women are the artist’s arbiters—107 of them, a tribunal of sorts—called upon to perform a difficult task: to read and render professional commentary upon a breakup e-mail that the artist received from her ex-lover, which ends with the line “Take care of yourself.”

Sophie Calle, Prenez soin de vous, 2007. Photo: Sophie Calle.

In Calle’s own words: “I received an e-mail telling me it was over. I didn’t know how to respond. It was almost as if it hadn’t been meant for me. It ended with the words ‘Take care of yourself.’ And so I did. I asked 107 women … chosen for their profession or skills, to interpret this letter. To analyze it, comment on it, dance it, sing it. Dissect it. Exhaust it. Understand it for me. Answer for me. It was a way of taking the time to break up. A way of taking care of myself.”

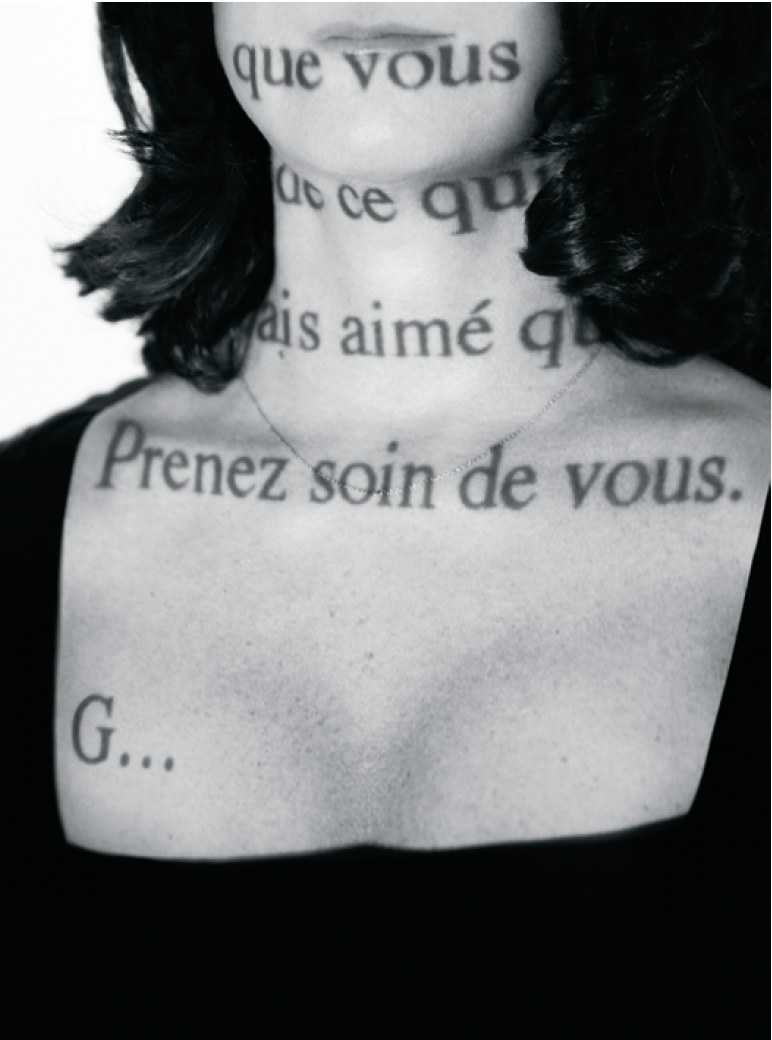

It is less about the guy, even though his egregiously crapulous e-mail was the catalyst. The acquiescence, the complicity of the women, has resulted in one of Calle’s finest works, hypnotic by any standard. Their voices, their professional vocabularies are foregrounded here and constitute a collage of texts, photos, films and voices that is a replete and, one supposes, balm and bridge to the future. Ranging from the clinically analytic to the emotionally heated, these responses are fascinating and revelatory of both the work these women do and the solidarity they demonstrate with Sophie Calle. Theirs is a healing art, convincing us that they have contributed to a triage in which there is now less open wound than resolute suture. However, I would still argue that the photographs take precedence, for they are incandescent one and all and figure as the trump card of the artist’s conceptual agenda, the ace up her sleeve. Icons of full disclosure and palpable enigma at one and the same time, they are the chorus that speaks of the prologue, epilogue and everything in between.

Calle has steadfastly refused to disclose the name of the man who wrote the breakup e-mail. That would have violated his right of privacy. Or would it? A callower, more vitrified cad of a man would be hard to imagine. Calle chooses, with the immense courage so emblematic of her work, to abrogate her own.

Calle’s art here is less one of willful revenge than breathtaking self-exposure—and a palpable act of mourning. It is not the fact that the name of her ex-lover is not to be disclosed that is paramount but her own refusal of amnesia, even as she seeks something like closure. The work is self-reflective, of course, but in its very nakedness, it is also heartrending. She infringes upon her own privacy. Not his. Her own. The sheer intensity of her obsessive working process, already a legend in the art world, is there for all to see. The work is fetishistic, but also self-mocking by virtue of surfeit, and luminous in excess.

Sophie Calle, Prenez soin de vous, 2007. Photo: Jean-Baptiste Mondino.

This issue of the name not given is nothing compared to her own transparency, then, her own vulnerability, her humanity, which is dramatically accented as a result. The exhibition speaks of her daunting strength as well as the fragility of the psyche. It also speaks of exorcism, catharsis … forgiveness, maybe? As Jacques Derrida notably said, the latter is the chaos at the origin of the world.

It is Sophie Calle who is deliberately placing herself in the spotlight, in the headlights, out on a limb, and it shows us more than anything else just how inextricably her body of work is intertwined with her own aorta. I can think of few other conceptual artists—few other artists, really—who work from such an intimate template of the lived world and who blur with such unerring savvy, and so unrelentingly, the distinction between public and private, inner and outer, reality and fantasy. This high-wire act, which her tremulous private self walks so nimbly, with virtuosity and fervor, is inordinately captivating. Hers is a profoundly autobiographical consciousness, high-risk and entirely unafraid.

One response in particular— that of her own mum, radiant in its stoicism and, one presumes, hard-won pragmatic advice— stands out for us here: “You leave, you get left, that’s the name of the game, and for you this breakup could be the wellspring of a new piece of art—am I wrong? I love you. Your mother.”

No, she was not wrong. And for that we should all be grateful. ■

“Prenez soin de vous (Take care of yourself)” was exhibited at DHC/ART in Montreal from July 4 to October 19, 2008.

James D. Cambell is a writer and curator in Montreal. His recent publications include Cheese, Worms and the Holes in Everything: David Blathwerick (Art Gallery of Windsor, 2008), A Mind of Winter: The Art and Thought of John Heward (Musée du Quebec, Quebec City, 2008) and On the Inside: Janet Werner (Parisian Laundry, Montreal, 2008).