Sophie Bélair Clément

Montreal’s Artexte, which has collected Canadian art publications for years, has recently moved to a new, purpose-built home. The new space has a beautifully appointed exhibition room, fancy movable book stacks and neo-modernist white meeting and study rooms. Notably, its brushed concrete floors and the black, white and grey interiors are the same sort as those favoured by contemporary art galleries, not libraries. As a hybrid space that puts the library on an equal footing with the art gallery, I see Artexte as a portent of future art institutions that will acknowledge the complexity of art by putting a great deal of energy, time and resources into creating an informational context for the exhibition of works of art.

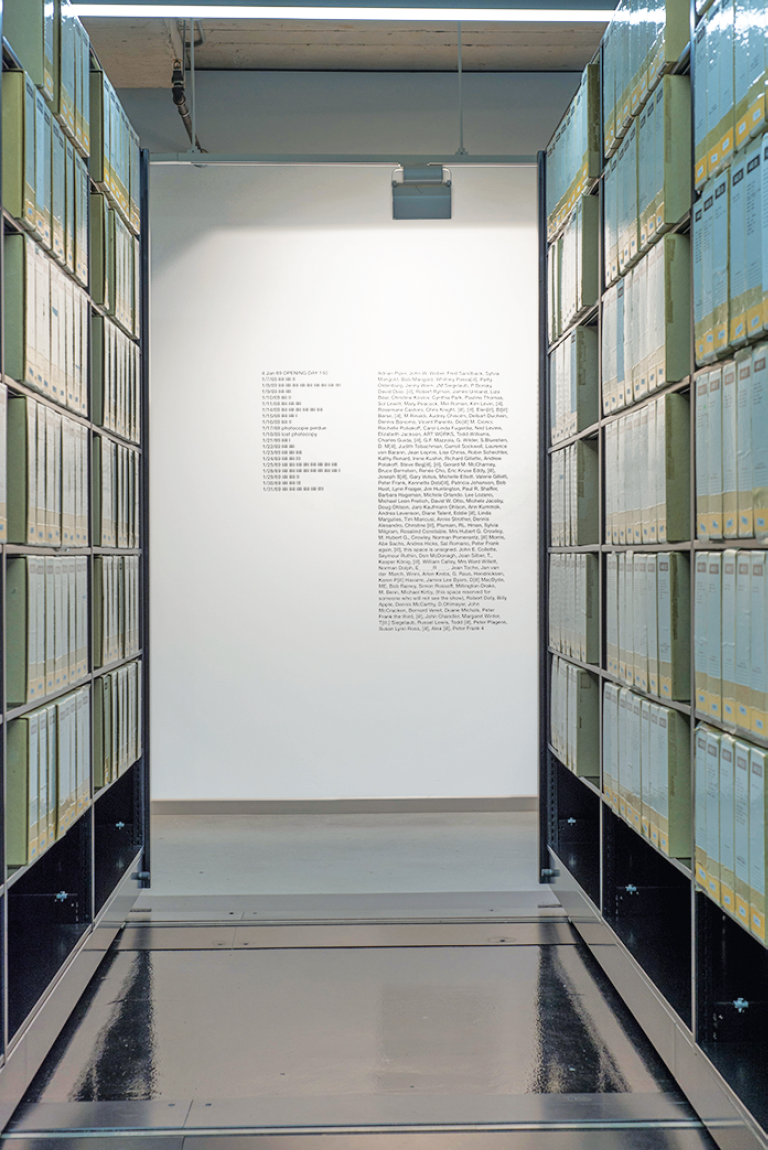

Sophie Bélair Clément, “2 rooms equal size, 1 empty, with secretary,(1),” installation view at Artexte. Photograph: Paul Litherland

It can be argued, of course, that some galleries already do this sort of thing, but I’d assert that the white cube art gallery’s tendency to isolate art by floating it in a seemingly neutral context-free space has, for about 100 years, helped to obscure, not illuminate, the embeddedness of works of art within many forms of informational culture that were, and are, essential for its comprehension.

Conceptual art has always highlighted information within and as art, so it is easy to argue for the fit of conceptual art to an enterprise such as Artexte, but that does not necessarily mean that Artexte needs to show only art, in this exhibition space, that is related to the traditions of conceptual art. That said, the recent multimedia exhibition of Sophie Bélair Clément can easily be argued for as an ideal candidate for an Artexte show.

The exhibition is based on a photograph taken by Seth Siegelaub in 1969, a grainy picture of what appears to be a typical office interior of the time, but what was actually one room of two that housed an exhibition of which Clément makes a fanciful re-enactment. Clément has reconstructed the office depicted in the photograph, but with important changes. She has made, for example, white porcelain-looking casts of notebooks, an ashtray, a book and a tabletop that transform these everyday things into glamorous sculptural objects. An audiotape of a woman’s voice reading notes and entries in a guestbook is played as a loop in the space. Clément has made a wall text on an outside wall of all of the names entered in the 1969 exhibition space’s guest book—a who’s-who of the late-’60s New York art scene that includes the names Lucy Lippard, Dore Ashton, Carl Andre, Robert Barry, Kaspar König, Iain Baxter, Vito Acconci, Jan Dibbets and more. Clément engages Artexte’s reception staff member as an “interpreter,” and there is even a performance element involving an actor who roams the Artexte complex.

Sophie Bélair Clément, “2 rooms equal size, 1 empty, with secretary,(1),” installation view at Artexte. Photograph: Paul Litherland

Such loving attention to the reconstruction of elements of an important historical show could be justified on several levels, but it could also, of course, be read as an extravagant fetishization of an original moment in the scheme of art history that places conceptual art at the end of a long avant-garde tradition. For people, me among them, who like the history of conceptual art, this work is like a carefully constructed manger scene for Christians or the conservation and restoration of a wrecked Old Master painting: there is pleasure in articulating for oneself how Clément puts her own gloss on the original photograph and show, almost as if the exercise were a 3-D Photoshop project in which the artist has taken great liberties with an image.

One could be swept up in a vision of endless iterations of Adrian Piper at a desk in the original photograph and Clément’s imaginative reconstruction, but there is also the matter of Piper’s participation as a woman in the original show to account for. As a young—and leading—conceptual artist aligned with older male colleagues at the time, one is reminded that Piper plays the role of secretary in the original show and photograph in a kind of pre-feminist social void. As we know, Piper went on to a distinguished career as an artist and academic philosopher, and it is not lost on Clément that Piper’s stereotypical role in Siegelaub’s show rates as an anomaly in what we might otherwise rate as—and this is always problematic in discussions of avant-garde art—socially progressive work. Of course, Siegelaub likely asked Piper to play secretary in his mise en scène for practical, documentary reasons: he wanted the situation, we presume, to look “normal.” Anything but, as we learn from Clément’s revisitation. ❚

“Sophie Bélair Clément: 2 rooms equal size, 1 empty, with secretary,(1),” curated by Eduardo Ralickas, was exhibited at Artexte from September 27, 2012 to January 26, 2013.

Cliff Eyland is a Winnipeg Artist.