Song-Lines

Popular musicians, writers and performers of songs have been around for a long time. They can be traced through art song and chanson, through the lieder of Schubert and Schumann, and further back to minstrels and troubadours. What all their songs have in common is their everyday importance within particular societies. Musically and lyrically they express the feelings, desires and ideas of the time in a manner that makes them almost universally acceptable.

Pop music, as we know it today, is largely a desert. The technology of recording and distribution, working hand-in-hand with a business sector that dominates our tastes and needs, has taken control away from both singer/songwriters and listeners. Human needs, by and large, are not being met. Yet, there are a few pop music artists who have created genuinely high-quality popular music and who continue to do so. They are to be valued.

Two recent books, Alias Bob Dylan and Some Day Soon, consider a handful of such artists; the former examines the work of Bob Dylan, and the latter reviews the careers of five Canadian songwriter/performers. Both publications, unlike the vast majority of books on pop artists, are well written and, in one way or another, take their subjects seriously.

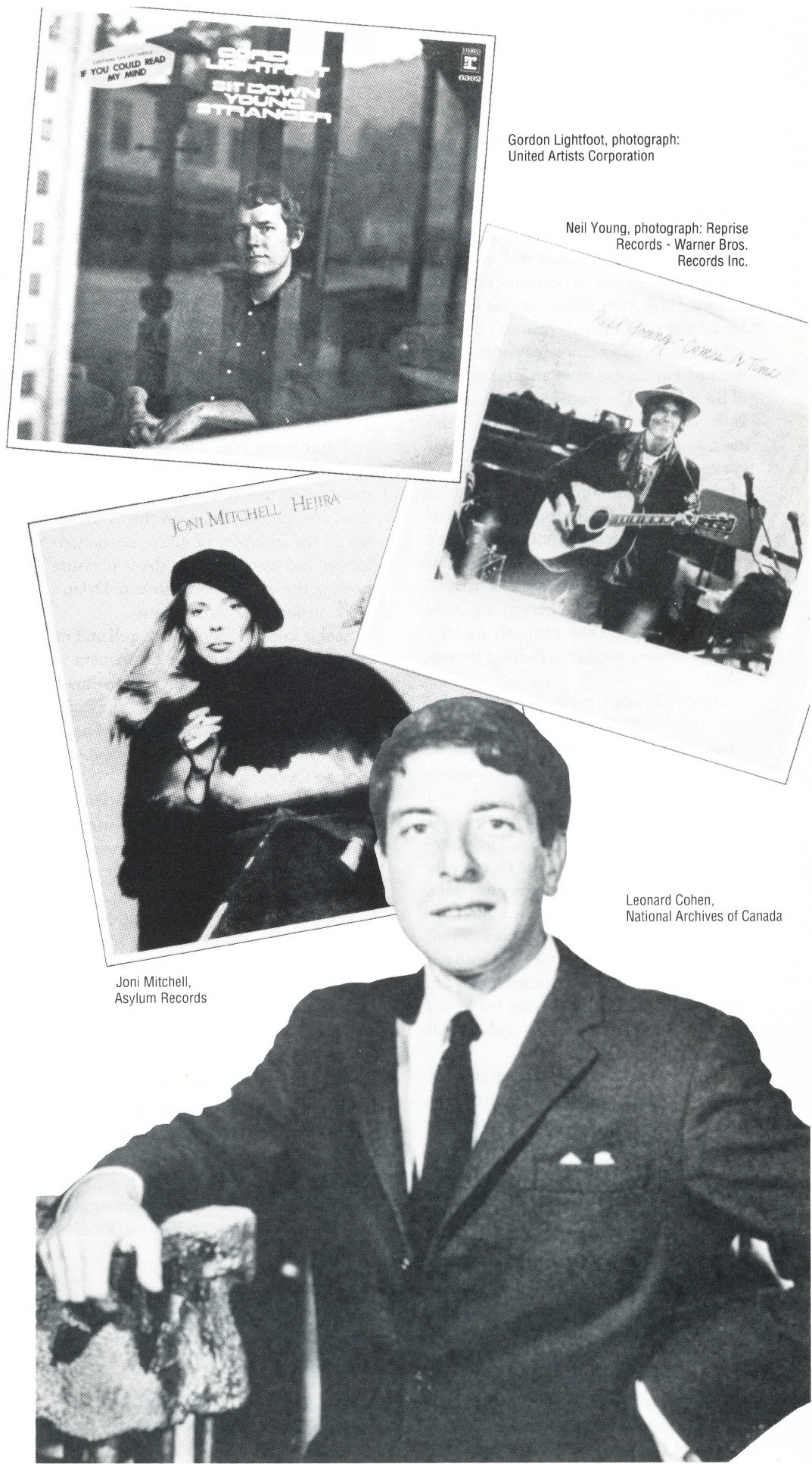

Some Day Soon, by Douglas Fetherling, brings to our attention the significant achievements of Leonard Cohen, Joni Mitchell, Neil Young, Robbie Robertson and Gordon Lightfoot. We’re used to thinking of the success of our popular entertainers in a two-tiered way: in Canada and in the United States. The quintet in Fetherling’s book has achieved recognition in both countries.

But this very distinction points to the first difficulty I have with Some Day Soon. Fetherling is too preoccupied with the possible definitions of Canadian. Are these musicians, in their styles, their lyrics, even in their diction, Canadian or not? What are the indications of Canadianness? It’s the kind of preoccupation that was interesting 20 years ago, but today this need to praise or pigeon-hole in terms of Canadianness is tiring. It’s most certainly a dis-ease.

To understand an artist’s national context can be valid and informative, but to carry on defining and classifying ad nauseam is unfair to the artist. It creates an environment within which the artist constantly has to prove him or herself in a way not asked of American, British or French artists.

Here’s an example: “After all, Lightfoot was a Canadian, his phoney red-dirt Okie accent didn’t fool anyone, and he didn’t have Dylan’s powerful outlaw tradition behind him.” Was Dylan’s singing voice, with an accent not exactly native to his birthplace, any less phoney? You might also ask, what exactly was this “powerful outlaw tradition” of Dylan’s in Hibbing, Minnesota? Is it possible instead that Dylan, as many artists have done before him, embraced an outside tradition that spoke for him and helped him place himself? Fetherling, elsewhere in the book, suggests Lightfoot’s cultural confusion by the fact that his song was entitled “Canadian Railroad Trilogy,” not “Railway.” Leonard Cohen’s confusion is evident in his pronunciation of schedule as skedul. Are these really telling observations?

I suspect my second difficulty with this book is interwoven inextricably with the first. Although Fetherling does credit these artists, his consistent tone (with the exception of the chapter on Neil Young) is one of deprecation, a quality often considered Canadian. Here is his description of an interlude in Joni Mitchell’s career:

What followed was a near soap opera, with Joni, the wounded Scorpio, popping up constantly in the papers, magazines and, in another guise and dimension, appearing each year with an album full of songs apparently wrung painfully from the very experience—sexual, emotional, or geographical—about which its eager buyers had been reading and gossiping.

Or this is the dismissive way that Fetherling summarizes Cohen’s recent comeback: “Yes, the doleful loner with the zippers on his wrists is emerging from the shadows once again, more or less on schedule.”

Leonard Cohen, in particular, comes in for mockery. Frequent references are made to his posing or pretending, “the aesthetics of pretending to be washed-up,” as Fetherling puts it. Words like “quasi-religious” also make the point. Fetherling has a bee in his bonnet over Cohen. But if you’re going to make a serious effort at understanding an artist’s work (and there is no indication that Fetherling is consciously writing a put-down), then surely you take the artist, at least to begin with, at face value.

Writing about Neil Young, Fetherling says:

His phrase structure is balanced, which emphasizes the sighing quality in his voice; but he often sings at the top of his range—more like Mitchell in that respect—thus emphasizing his vocal unattractiveness, for want of a better word; at times he could almost be sending up poor Leonard Cohen, who of course can’t help the way he sounds.

In other words, Neil Young, when he misses the note or when he strains, is doing it intentionally, while Cohen, doing a similar thing, is musically inept. This biased observation doesn’t bear scrutiny.

I find Some Day Soon uneven in treatment in another respect. While Fetherling goes into considerable musical detail in his chapter on Lightfoot, his piece on Robbie Robertson is more or less a chronological summarizing of the songwriter’s career. Young is taken at face value, his myth repeated in a general, non-critical way.

Still, there are things of value in the book. His analysis of Lightfoot “as an artist of mood rather than form,” his discussion of Mitchell’s forays into jazz, his drawing the connection between Dylan’s John Wesley Harding and the Songs of Leonard Cohen, and his observations on Robertson’s mastery of “the deeply felt historical song” are examples of Fetherling’s discerning awareness. When he brings together his insight, knowledge of music and his seriousness of purpose, he writes the way I wish the whole book were written.

Alias Bob Dylan self-consciously takes Dylan out of the popular bedrock his work emerges from and places him in academia. Stephen Scobie, poet, critic, academic and Dylan aficionado, at least partially acknowledges this problem. He knows he’s damned either way: academics will say Dylan is not deserving of serious critical theorizing, while fans may well recoil at the songwriter’s forced occupancy of such hallowed and stuffy realms. Scobie knocks his subject right through heaven’s doors.

His cautionary acknowledgement does not prevent Scobie from an over-reading of his subject. The easiest example of this is the analysis of Dylan’s use of the word ain’t. Grammatically speaking, this word creates a double negative, but it’s also one of the most common usages in popular song and is not meant as a double negative. It’s a regional colloquialism that’s been taken on by much popular music, in particular country, blues and rock ‘n’ roll. If ain’t is going to be taken so seriously here, why not do the same thing in a Muddy Waters song or a Rolling Stones song?

Dylan’s lyrics simply can’t bear the scrutiny Scobie applies to them. Nor should they have to. They don’t belong in academia to begin with. Dylan has always been inconsistent, both musically and lyrically. He’s written some of the best songs and some of the worst and he’s never pretended otherwise. Quite recently he was quoted as saying he sometimes churned out songs to fill an album, or even released albums to meet contractual demands. Scobie doesn’t take this into account, or, rather, the inconsistencies are embraced as part of the Dylan mask. No matter what Dylan comes up with, it will fit Scobie’s theory.

Of course he has pre-empted all such criticism by announcing in the first chapter that the author is “dead,” that we can only deal with the text as it exists, not with any authorial intentions. Quite simply, you accept this or you don’t. I used to hear that the Bible was infallible because the Bible said it was infallible. Everything’s self-referential, self-enclosed and correct. All critical entry points are closed off, arguments pre-empted.

And yet, when it comes to supporting the theory, the author isn’t quite dead. Scobie spends a fair amount of time looking at Dylan’s birthplace of Hibbing, Minnesota, particularly at the duplicitous origin of the town’s name. Again, he would argue this is part of the text. I’d simply add that if the author’s biography is part of the text, then, surely, the author’s occasionally voiced intentions are also part of the text, as are his favourite colours or smells, who he is married to and so on.

But why bother? Don’t we end up where we began? With the author and the words and the music? Once you get past the academic heaviness of the book, there is much here to relish. Any Dylan fan has always known he wears masks, is shifty and elusive, but here it all gets put together. I found myself humming the songs mentioned in the text, or, more often than not, putting them on the CD to listen to the interplay of voice, instrumentation and words. It was sheer pleasure hearing the interwoven nature of Dylan’s work, making the connections.

Scobie knows Dylan’s work well and he brings along with him the excitement of discovery. In his explanation of the mask in classical theatre, he writes, “the voice was the ghost within the mask.” This is what the book, at its heart, is about. It’s vintage Dylan.

Scobie concludes that “Bob Dylan has never advanced in a straight line; his most characteristic move has always been the sidestep. Hell, just call him Alias. That’s what I do.”

But Scobie can’t help himself. He goes well past calling Dylan Alias. He is a Dylan fan and an academic. He tries to fuse the two and in the attempt has written a book with an irrelevant theoretical colouring. But, because of Scobie’s grassroots knowledge of Dylan, because of his infectious enthusiasm and, in the end, because the subject is inherently interesting, Alias Bob Dylan remains a fascinating book. ♦

Patrick Friesen is a Winnipeg poet, playwright and filmmaker. His most recent play, The Raft, is part of Prairie Theatre Exchange’s 1991-92 season.

Some Day Soon; Essays on Canadian Songwriters, by Douglas Fetherling Kingston, Ontario: Quarry Press, 1991 Paperback, 176 pp., $14.95

Alias Bob Dylan, by Stephen Scobie Red Deer, Alberta: Red Deer College Press, 1991 Paperback, 192 pp., $12.95