Sky Glabush

I rarely get the magic in contemporary painting. Often, I find myself at openings overcome by an impulse to splash the beer I’m holding across the canvasses because it occurs to me that the pee colour and stale smell of hops might deliver a dose of the unpredictable and resuscitate an image which seems to have died somewhere along the way. The impulse makes me feel curmudgeonly, as if I’m missing the train and will enter old age without ever having understood the value of my own generation. My mind wanders. Invariably, and by preference, it moves backwards in time to the ambient hum of Agnes Martin’s grids or to the palpitating peach yellow glow of early de Koonings. There is something in the mystery of those pictures that has gone missing; perhaps it is just the way those works seemed to have happened all at once and appear indubitably right that makes me feel giddy and defenseless—a feeling that I am forever chasing.

And then suddenly, unexpectedly, there it was at MKG127, a diminutive space on Toronto’s Dundas Street West, at the recent exhibition of Sky Glabush’s “Display.” In their mix of styles, the pieces looked thoroughly contemporary, but their surfaces had been activated with a force akin to the great Modernists. There is pathos in Glabush’s new work, a magic that belies a fragile balance of careful planning and chance occurrence—somewhere between control and chaos.

Sky Glabush, screen, 2014, paper, ink and screen on panel, 48 x 63.5 inches. Courtesy MKG127. Photographs: Toni Hafkenscheid.

The nine pieces in “Display” are marked by an economy of means: low in visual incident, thick with affect. The excitement they elicit is hardly just the result of Glabush’s attention to formal design (though he is a master of building tension in his compositions), but is the product of his translucent layering of pigment and his subtle build-up of sharp staccato marks which dance on the surfaces like the interference on an old TV screen.

The works are mostly two-dimensional abstract collages, save a series of small clay pots that sit precariously behind the gallery’s reception desk, and they are a fine network of simple, geometric forms floating in indeterminate spaces of warm red-greys and flake-whites. A mix of paper collage, graphite, paint and, in one case, a kind of Rauschenbergian “Combine” of paper, ink and a wire mesh window screen in a virtuosic display of simplicity and restraint.

In its entirety, the exhibition seems to operate like a kind of cryptograph, with the serial rendering of simple geometric forms—the square, circle and triangle— functioning like cyphers that impose a kind of linear sequence upon the entire show.

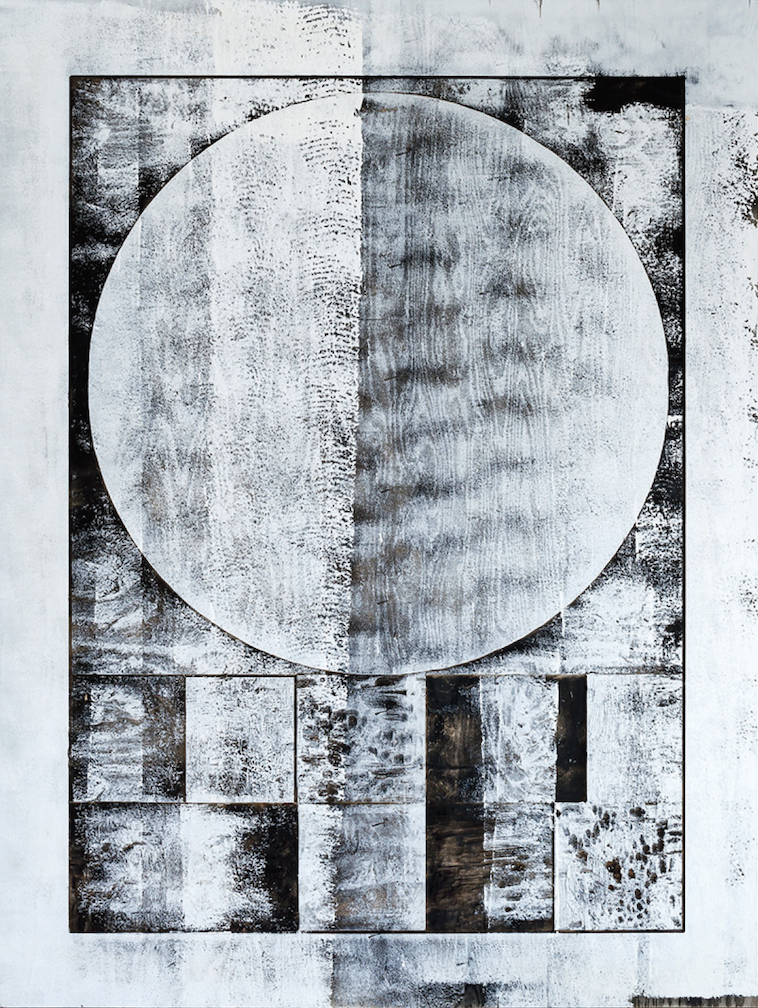

Moving clockwise along the wall, the purity of the shapes are contaminated by obscure allusions to Glabush’s past. A curious tension builds on the surfaces, a kind of dialectic between the vocabulary of mid-20th century Modernism and Glabush’s own personal archive of memory-images. The show opened with moon, 2014, a large, monochromatic sphere—made with acrylic paint on routered plywood—split down the middle like a cratered lunar yin-yang, suspended in a dense grid of overlapping white on black planes. Paint roller marks scraped across the surface work to cancel certain areas of the image while drawing attention back to the tactility of the material’s impasto application.

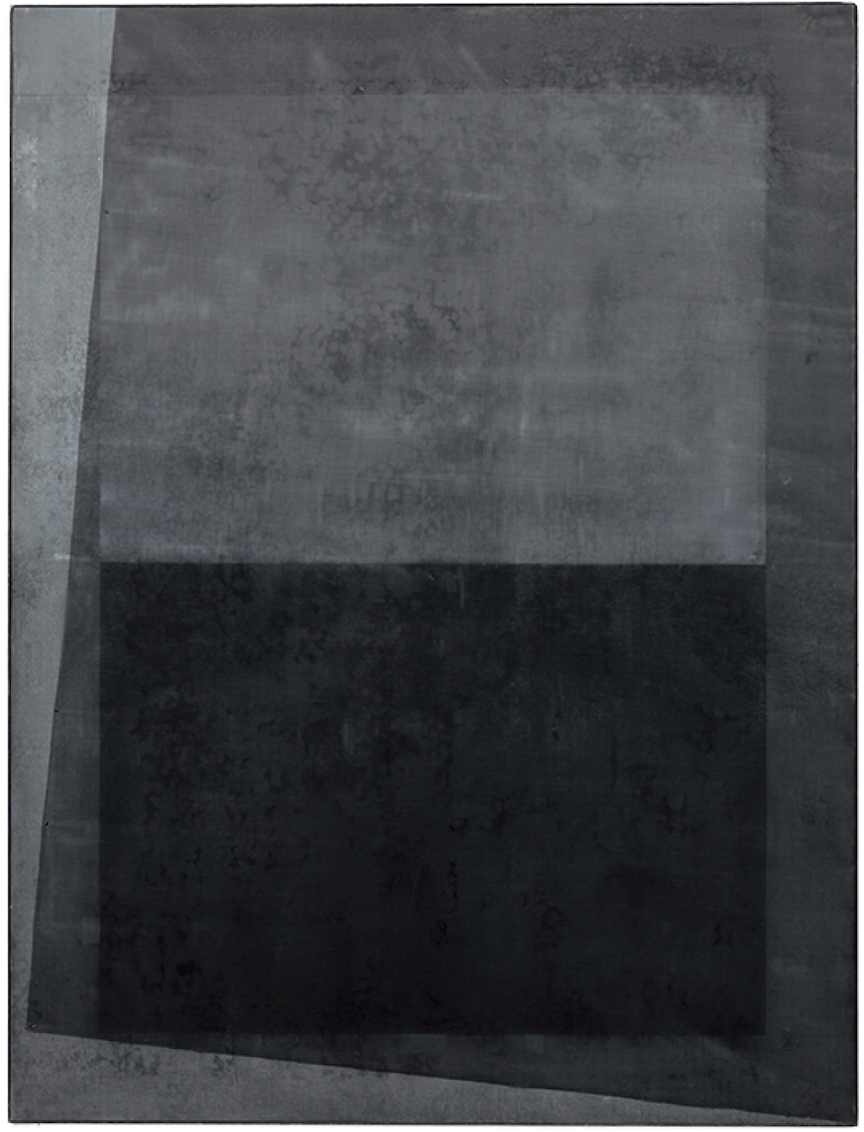

display, 2013, graphite on paper, 97 x 58.5 inches.

Moving clockwise from east to west, the sphere features again in the first collage of the gallery’s tiny second room in topography, 2014. Here, however, its form has splintered into a constellation of smaller circles and is now offset by a legion of humble squares. Peeking out and disappearing into a smudgy layered grey grid, the simple geometric shapes seem to be vying for attention, shrouded as they often are behind a roughcast screen of graphite lines.

The elements proliferate in the subsequent collages travelling west: now the perfect form of the square migrates into an irregular rectangle and then a triangle emerges as a further permutation of the series. As you move along, the shapes become less intelligible, their rhythmic, clean geometry increasingly punctured by biographical references, like lacerations on the silken skin of a newborn.

To the art world Glabush is something of an enigma. From his early hyper-realistic suburban landscapes, to the fulgent, geometric abstractions of his first solo show at MKG127, “Background,” 2011, to his most recent endeavour in collage, he is forever skirting easy categorization. There is, however, one current that seems to flow uninterrupted through all his work: the mining of his own biography. Whether it is the melancholic terrain of London, Ontario where he moved to accept a teaching post at the University of Western Ontario or the symbology he envisaged in “Background,” which cheekily makes reference to the “alcoholics anonymous” logo (a private allusion to his boozing parents) Glabush is perennially fixated on the phantasmagoria of his past. But the function of this past has become increasingly more complex in his last two exhibitions with his adoption of a modernist vocabulary. No longer only a conceptual device, it now functions like a landmine, blasting through the steely crust of formalist ideology.

“Modernity was an effort to take materials—the language of painting—and let their materiality become the subject,” Glabush told a small group gathered at MKG127 last April. “Where modernity became diluted was in Formalism.” For Glabush, Formalism “was only about the relationship between one beautiful thing and another beautiful thing. I wanted to contaminate that, but keep the material language.”

moon, 2014, routered plywood and acrylic paint, 48 x 63.5 inches.

Contamination is a loaded word. Its literal meaning is to make something impure. But for Glabush, contamination is more playful, like a child’s sticky hands on a pristine surface. The word also harks back to the picture of modern art imagined by the French philosopher, Georges Batailles, who saw the trajectory of Modernism as a series of successive pollutions or contaminations that render its subject matter progressively more obscure.

“Display” culminates in the title work, Display, 2013, the only truly representational image: a meticulous graphite rendering of a Bahá’i temple. It is a reference to Glabush’s father’s late-life embrace of the Bahá’i Faith. From a distance the image’s carefully modulated grey scale perfectly replicates the faded magazine cutouts of the collages to its left. When you move toward its striated surface, however, the image seems to be enveloped in a kind of film or skin. Inching closer still, the skin dissolves into a tight grid of carefully calibrated horizontal and vertical bands and then begins to decompose and crumble into a thousand tiny pointillist dots like particles of dust or memories bleached out by time. The work transforms before our eyes like magic. In our constant shift of orientation it opens up a deep tension between resolution and dissolution: the throbbing pendulum that is the living history of art. ❚

“Display” was exhibited at MKG127, Toronto, from March 22 to April 26, 2014.

Mira Berlin is an artist, freelance writer and graduate student of Art History at McGill University.