Sky Glabush

Before mass cynicism set in, there was Utopia. There were manifestos; dreams of grander things and rumblings of deep change in the belly of the world. Art was going to make the world a better place.

Edmonton artist Sky Glabush admits he is trying to tap into the wellspring of idealism that animated Modernism, the force that lent early 21st century’s dovetailing forms and media the heft of conviction, before it was perverted by a cannibalistic consumer culture— its language thieved and neutered, and suburbia a separatist parody of community.

Glabush’s process-heavy, thought-laden paintings of modular living spaces (minus their occupants, who are implied rather than present) are an ongoing exploration of how and where we, as a culture, lost the belief in Utopia. The new work looks at how the Western societal idea of coexisting within an environment conducive to inclusion and togetherness has fallen into an atmosphere of pervasive, shabby and derelict alienation. His work also discusses the notion of our personal and collective environments as representations of our singular and group beliefs, and how we negotiate our shared space, physically, aesthetically, politically, commercially and culturally.

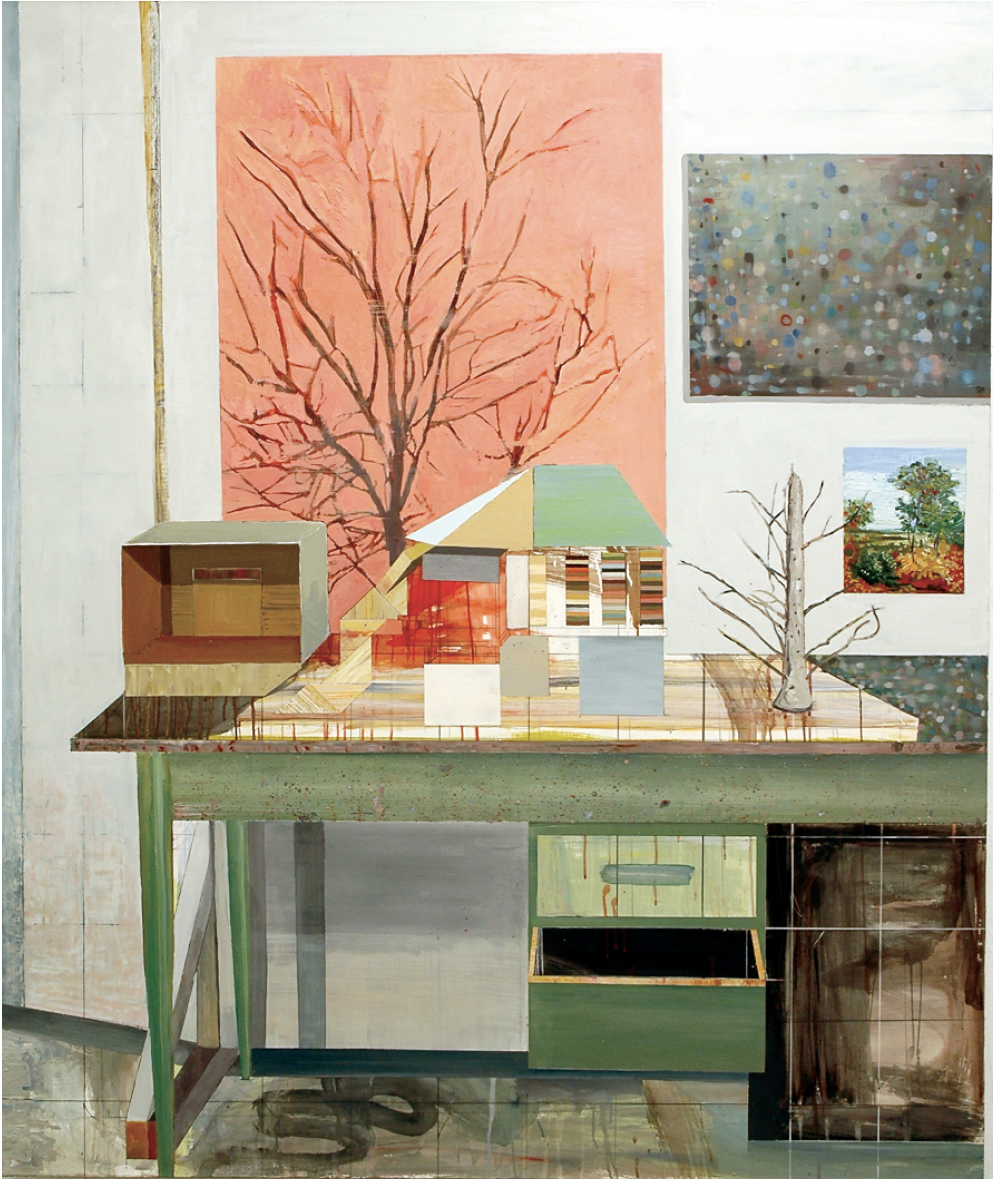

Sky Glabush, tree in studio, 2005–06, acrylic and oil on paper, mounted on canvas, 72 x 60”. Photo courtesy Douglas Udell Gallery, Edmonton, and the artist.

The creation of each of Glabush’s paintings, which appears at first glance to be a flat representation of an orderly, box-like, apartment block—perhaps a builder’s model or even a dollhouse for the slightly cheaper Barbies—is the result of an elaborate, near-ritualistic preparation before the artist even sets brush to canvas. Glabush begins with a construction, building a proto-maquette of a fictional environment that is seemingly heavily influenced by his recent years in Amsterdam. The European reference is the anti-sprawl, following the habit of building in a cluster rather than our avaricious, North American compulsion for expansion.

The models are neither ornate nor constructed in a particularly careful way. Rather, they have a touching naïveté and form and textural revelry about them that suggest a contest for kids who want to be architects when they grow up— the kind of aspirational reaching that is perpetually confounded by materials, and perhaps skill. Glabush intentionally uses scraps of crafty leftover-type things to build his modular constructions: cardboard, duct tape, Astroturf, popsicle sticks and other art-room leavings of that ilk. They also carry a faint nonsensical whiff of architectural curiosities such as the notoriously, inexplicably random, haunted Winchester house, which seriously blurs the line between functionality and sculptural mischief.

A personal language has sprung up to describe this body of work within the artist’s practice. Although he classifies the series as a deliberate attempt to delve into and replicate the mindset of modernists such as Piet Mondrian, Glabush has borrowed the lexicon of architecture and developers and created a literal cant for an urban geography all his own. Stages of his modular creations are termed “platforms,” rooms are called “cubes.” Other quirky pet names for his project components spike his discussions on the micro-environments. There are also narrative threads running through the models. Glabush confesses to silently imagining the inhabitants of each of the cubes as he constructs their living quarters and thinking about the ways their small worlds jostle each other within the context of their collective space. Photographing the urbanscapes he creates is, according to the artist, a vital intermediate step towards the final painting. Glabush rigorously sets up his models and experiments with composition and visual effects that give the impression of dimensionality within the frame generated by the camera lens. The photos function almost like preparatory sketches for the final canvas.

Sky Glabush, church dance, 2006, acrylic and oil on canvas, 60 x 73”.

A loose under-painting makes up the first layer of Glabush’s canvases. Though instinctively drawn to laying down a wildly physical and chaotic field of abstraction, Glabush seems slightly murky on why he feels he has to include abstraction in his work. The abstract ground does, however, function aesthetically to give texture to the canvas as well as a metaphorical hint of a churning, emotional existence hemmed in by his almost aggressively benign spaces.

With both the model and photo present as references in front of him, Glabush draws the environment on the canvas, almost obliterating the under-painting. He seems to be attempting to translate texture from the physical model to the canvas, instead of adding texture during the painting stage, and this weird reversal helps to give the canvas a sleek, glinting, coldly contemporary look that stands in stark contrast to the source work of the deeply flawed models.

That quality of chilly beauty within the final product disturbs the artist. Glabush is unsure why his paintings turn out ‘dandified’ when he is struggling to faithfully capture the rawness of the original models. Yet, in a way, Glabush’s dialogue between natural and real and an ideal that seems divorced from the everyday neatly echoes the concerns of the modernist era, where grandiose and beautiful notions of a particular brand of Utopia were hijacked or mutated to serve ugly movements. Glabush notes that he not only tries to see the bright dream behind Modernism, but how it darkened as the world turned to fascism, socialism and other isms that promised collective Utopia but delivered private miseries, before withering beneath the vapidity of today’s thoughtless use of space. ■

Sky Glabush’s “Living Together” was exhibited at the Douglas Udell Gallery in Edmonton from February 18 to March 4, 2006.

Christa O’Keefe is an Edmonton-based freelance writer.