Sky Glabush: Painting’s Alphabet

“Landscape has always been an ordering principle,” says London, Ontario-based painter Sky Glabush. “It is an underlying logic of space.” But there is an additional logic involved that has to do with the way language and image intersect in his imaginative process. In 1997 when he was an undergraduate at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon, he was doing a double degree in English and the visual arts. He recalls that literature interested him more than art and he “stumbled into painting.” It turned out to be a fortunate fall.

What is clear, though, is that literature, especially poetry, has stayed with him. When he talks about painting, he will mention painters like Cézanne, Matisse and Rothko, but poets, including Al Purdy, Seamus Heaney and Emily Dickinson, naturally enter the conversation. It was through the poetry of Al Purdy that he came to the realization that the landscape of southern Ontario provided him with everything he needed to make paintings, and it was a poem by the Irish poet Seamus Heaney that gave him the language to talk about the “new calligraphy” in his paintings. From Emily Dickinson he borrowed “every wild bluebell,” which he then used as the name of a painting that he combined with looking at Van Gogh’s irises. Words and images in the same imaginative frame.

Sky Glabush, Early light at Roblin Lake, 2024, oil and sand on canvas, two panels, each 213.36 × 243.84 centimetres, overall: 213.36 × 487.68 centimetres. Photo: Olympia Shannon. © Sky Glabush. Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and New York.

Sky Glabush’s exhibition called “The letters of this alphabet were trees” was at the Stephen Friedman Gallery in New York from September 5 to October 16, 2024. What follows are excerpts from a phone conversation with Robert Enright recorded on Thursday, November 14, 2024.

I make small sketches on whatever piece of paper I happen to have, either a sketchbook or just an envelope. I’m on the prowl or my antennae are raised because I need to get into a condition where I’m actively thinking about a painting. It’s not anything physical or concrete. It’s turning on a switch. It could be in a used bookstore; I can come across an image, see an album in a record store. It can be at a museum; I can be walking down the street. A lot of my paintings involve a reverse ontology where I’m attracted to something in nature because I’ve already seen it in a painting. So the initial stage is being open and receptive and alert and looking with a particular kind of eye. In some ways it’s the most critical part. In that process I’ll either take a photograph, make a mental note, write down words or sometimes I’ll make a drawing. Then I do watercolours. I’ll do 50 or 100 of them. Most of the time they remain studies, but I might paint one or two in large scale. All the paintings in New York were based on small watercolour studies. I try to be faithful to the spirit of the watercolour, but I’m not copying it. Then I destroy the connection to the watercolour. I’ll completely move away from it. If the painting is all blues and greens, I’ll change it to reds and pinks. When you see them over eight or nine feet, the larger painting is a radically different thing. I’m not interested in making a reproduction of the watercolour, but it does contain the germ of the idea or the energy.

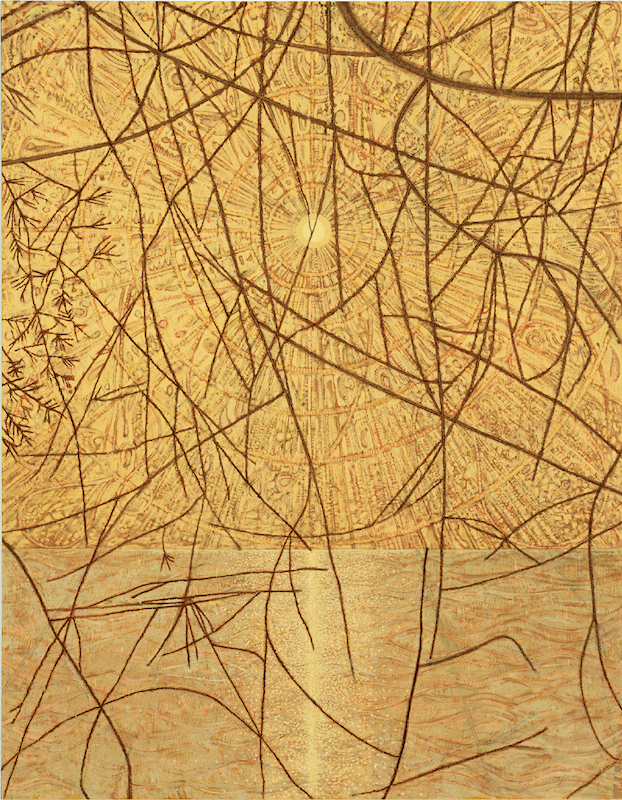

Sky Glabush, The letters of this alphabet were trees, 2024, oil and sand on canvas, 274.32 × 213.36 centimetres. Photo: Joseph Hartman. © Sky Glabush. Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and New York.

One of the large paintings in the show is called Logging road at night. It’s a very dark blue. The bottom passage is silvery and looks like light reflected on water or ice. That painting happened really quickly. There was no going back in that one. There was no destroying; there was no reversal. I did the whole painting in one go, and that almost never happens. Most of the time my work is a process of building and destroying and building and destroying. If it’s not working, I find a way into it, a way through it. I do something to make it alive.

The title for the exhibition comes from a Seamus Heaney poem called “Alphabets.” In the poem he’s talking about a child and I think he’s also talking about himself. He says, “For he was fostered next in a stricter school / Named for the patron saint of the oak wood / Where classes switched to the pealing of a bell / And he left the Latin forum for the shade / Of new calligraphy that felt like home. / The letters of this alphabet were trees. / The capitals were orchards in full bloom, / The lines of script like briars coiled in ditches.” That poem is the perfect articulation of what I’m looking for as an artist. The “new calligraphy” that he finds in nature is a perfect phrase. It’s a written language. It’s written in a painting but not just any kind of painting. It’s a gestural, graphic, rhythmic line. Then he says that new calligraphy feels like home. That’s also what I’m experiencing: when you distill what you recognize in nature in an image or in a visual experience, it’s a way of recognizing your own place in the world. You could call that home. The meaning comes from feeling your identity confirmed in a particular place and particular time. What was new for me was the acceptance that I’m in Canada, in southern Ontario, making landscape painting within a very conventional, even banal kind of space. I was accepting that within it there was something infinitely beautiful and full of potential, the realization that everything I need is right in front of me.

Installation view, “Sky Glabush: The letters of this alphabet were trees,” 2024, Stephen Friedman Gallery, New York. Photo: Olympia Shannon. Courtesy Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and New York.

The first painting I ever did where I used sand was in a show I had at MKG127 Gallery in Toronto called “Background.” I was making a break from the largescale landscape paintings I had been doing for a few years and I’d stopped cold. The problem was I had been working directly from photography and it was stillborn. The process itself was killing the creative spirit in the painting. I was like a person drowning, and in that desperate search I realized that the spirit wasn’t in the image, it wasn’t in the landscape, it wasn’t in the picture. Painters will know what I’m talking about; you’re flailing around in the studio and you’re moving things around and you’re trying things out, and all of a sudden you get into this space where it feels like light or energy is flowing through you. It’s almost revelatory. Those are the moments you’re looking for. One of the paintings I did in that show was called Up/Down, and if you looked it could be a pile of dirt or it could look like the stars. It was a callback to a psychedelic trip I’d had when I was 17 where I blew myself completely to smithereens. My face was pressed into the mud and I was looking through the ground and the heavens were opening up. In that painting I used dirt and sand to create a celestial space that was completely gritty and dirty and looked like a piece of a parking lot or a gravel road. But in another way, it looked like the stars.

If you look closely at The letters of this alphabet were trees, there’s the little lattice of light, or a circular radial pattern in the sky that almost looks like a zodiac. I got that by erasing everything. It was a bright orange painting, and I got to the quality of light by removing all the orange and covering over it with white to allow little slivers to remain. Technically, all that stuff I’ve been talking about was there—the sand, the paint, the covering—and it was very, very intense.

Sky Glabush, Logging road at night, 2024, oil and sand on canvas, 243.84 × 182.88 centimetres. Photo: Joseph Hartman. © Sky Glabush. Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and New York.

There’s light that exists in nature, but it’s not the same light that exists in painting. Think about Vermeer. There’s no light in Vermeer. He’s using colour to make it feel as though it’s illuminated. It’s a trick, but it’s not really a trick because there really is a light in there. It’s not an illusion. There’s light in a Vermeer painting that is palpable and undeniable, but it’s not reflective photons coming from an external source. The light is inside the painting.

Landscape has always been an ordering principle. There’s an up and a down. There’s almost always a horizon. There was a time when I thought it was the kiss of death to be labelled a landscape painter, but then I stopped trying to create an image of who I thought I should be. I let go of the idea of trying to be a contemporary artist; I started following my instincts and following my heart in the work itself. It led back to a quite conventional approach to landscape. Once the logic of the image is established, I am actually not thinking about the landscape. I start to treat the surface like an abstract painting. I’m just putting green beside yellow, yellow beside red, red beside pink. I’m trying to make something dark. I’m trying to make it light, to make it have energy. I’m trying to create relationships. I treat it like a Clyfford Still painting. I’m not comparing myself to him; what I’m saying is that in a raw and visceral way I want to create moments of tension between things, especially with colour and light and dark. I don’t care if it looks like a leaf or a reflection on water. That’s just an ordering principle. Which was how I felt when I was making abstract paintings. In some ways, the two worlds are more unified now than they were before.

Sky Glabush, River through trees, 2024, oil and sand on canvas, 243.84 × 182.88 centimetres. Photo: Joseph Hartman. © Sky Glabush. Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and New York.

Early light at Roblin Lake started off as water. The entire surface was water and I was basically trying to do the lily pads in the pond at Giverny. And I got completely lost: intellectually, conceptually, lost even in spirit. It was terrible. I thought I could take Monet on, and I realized I was losing this battle really badly. So in a last-ditch effort to save that painting, I drew those vertical trees. I took the painting from a big, open, watery pond to a lake, to come back to something I could understand again, or some place where I could ground myself. I know where the landscape stops and the painting begins. The intersection of a plane meeting another plane is an extremely critical moment. I left all the trees at the bottom of that painting, like cartoon outlines. There was no effort made to root them at all. There’s no shadow.

I used to revel in the space of doubt, but it’s not doubt anymore. It’s more like I’m purposely getting lost. I get these small studies up on the canvas and they look terrible. When I blow them up, they look like a bad copy of something. But then I start to refine and clarify and simplify. It’s a lot of taking things away. And still the painting doesn’t look like anything. It looks dead, contrived. Then I abandon thinking about image or the landscape. I abandon thinking about flowers or light and I start flailing around with the painting, hoping that something will happen that gives me a direction. The interesting thing is the painting almost always suggests a way out. That isn’t coming from me, but it’s something I am provoking in the painting itself. I think the difference between myself now and 15 years ago is that I trust the painting will speak to me and I’m more attuned to hearing it.

Sky Glabush, Every wild bluebell, 2024, oil and sand on canvas, 50.8 × 61 centimetres, framed: 52.1 × 62.2 centimetres. Photo: Joseph Hartman. © Sky Glabush. Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and New York.

River through trees was a real effort. I spent a couple of months working on it and I didn’t feel any pressure to finish it. There are big vertical trees, almost like bars in front of a screen, and they look like a middle passage, a middle distance. That screen took me weeks and weeks and weeks to paint, and it never worked. It looked like a jumbled grey mess of lines. There was all this energy in the middle of the painting, but that energy had to recede. It had to disappear. It had to be both incredibly knotted and dense and compressed and intense, and also be wispy and airy and fade away, and I could never get the balance right. The top part is almost like a Japanese approach to cherry blossom painting. That language at the top quarter of the painting, which is all branches, is totally different; you’ve got calligraphy, architecture, gesture, fractal. The middle is a dense, completely compressed, knotted space. Then the bottom opens to the river, and the very bottom is a pink, light, snowy space. Each one of those intervals, each one of those planes, and each one of those transitions was really difficult. The vertical trees change colour. At the bottom they might be really light, and at the top, they transition to really dark so they’re acting as an interlocutor, as a bridge. They’re taking what’s going on at the very top of the painting and letting it travel down into what’s happening at the bottom. That painting is a negotiation of abstraction and gesture. It is just play and intuition, and it’s also trying to make a photorealistic landscape painting, except I wasn’t using a photo. I was working only from my imagination.

If there were one artist I had to have in my studio as a source, it would be Paul Klee. He understood what I’ve been describing about the relationship between process, abstraction, intuition and an ordering principle. Paul Klee is the artist who shows that you could use a figure, a fish, a loaf of bread, you could use the stars, and they can be arranged and embroidered into a wild cosmological and magical tapestry, like a dream. He created a completely unique language. He’s the greatest teacher; I’m constantly looking at Paul Klee and I will make a flower like his in my work, or I will make a Van Gogh flower. I don’t have a problem with that. In fact, it’s the opposite. I can’t understand painting as an intellectual exercise. If I want to understand Van Gogh’s flowers, I have to paint them. Sometimes those copies are for my own technical and intuitive development. Sometimes I’ll destroy them and build over them. There’s a little painting in the show called Garden Painting, where the bottom third is almost a verbatim copy of Tom Thomson. But the top third is totally my own work. I’m putting myself in conversation with him. Because if you fall in love with something, if you’re infatuated, it’s going to make its way into your thoughts and intuitions. It’s almost like an addiction. There were a few artists whom I was heavily in love with. Klimt was a big one and I was looking at Monet. I had been to see the Monet Water Lilies many times. This last time when I was in New York at MoMA, I came into the room with the Monets, and it was like I saw them for the first time. My knees just buckled. These paintings are gritty and they are messed up and dirty, but they’re also perfectly executed and gloriously beautiful.

Sky Glabush, Garden painting, 2024, oil and sand on canvas, 45.7 × 35.6 centimetres, framed: 47.3 × 36.8 centimetres. Photo: Joseph Hartman. © Sky Glabush. Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and New York.

When I get to an impasse in a painting, or I get the painting to a certain place where I’ve fulfilled the initial obligation to the study, sometimes I’ll spend days looking at it. I’ll sit in my studio and stare at it. I’ll fall asleep in my chair, and I’ll wake up and I’ll look at it again. I’ll go for lunch; I’ll come back; I’ll keep looking. In my last show at Stephen Friedman Gallery in London, I was working on a large mountain painting, and the deadline was looming, the clock was ticking. I spent over a week just staring at it and being paralyzed. I couldn’t do anything. I’d get up to make a mark on the painting, and then I’d sit back down again. But at some point something does open and you respond to that. It’s not so much confidence that I can make it happen. It’s more confidence that it’s there and I have to open myself up to it. ❚