Skull-Busters

In the post-war period, with the emergence of suburbia and middle-class mobility, North American society became increasingly aware of the disturbing trends of delinquency and youth violence. Inevitably, Hollywood took notice with well-intentioned but outdated flicks such as Rebel Without a Cause and The Blackboard Jungle, made under the assumption that if mom and pop were just a bit more attentive to their boy, he wouldn’t be messing around with those punks down the block. Since then, mainstream filmmakers have toyed with a number of variations on this theme, from the archetypal misunderstood youth (The 400 Blows or The Outsiders) to more notorious examples where teen hoods were elevated to anti-establishment symbols (A Clockwork Orange or Quadrophenia). The Canadian variant of this genre occupies the former category, best represented by National Film Board docudramas like Nobody Waved Goodbye and Train of Dreams, realistic social commentaries which either lamented when teenagers went astray or posited solutions about how to put them right again. But now in his first feature film Hell Bent, Winnipeg filmmaker John Kozak abandons this moralistic approach in favour of a rawer and more vitriolic illumination of what happens when a trio of unruly teens go wildly and hideously out of control.

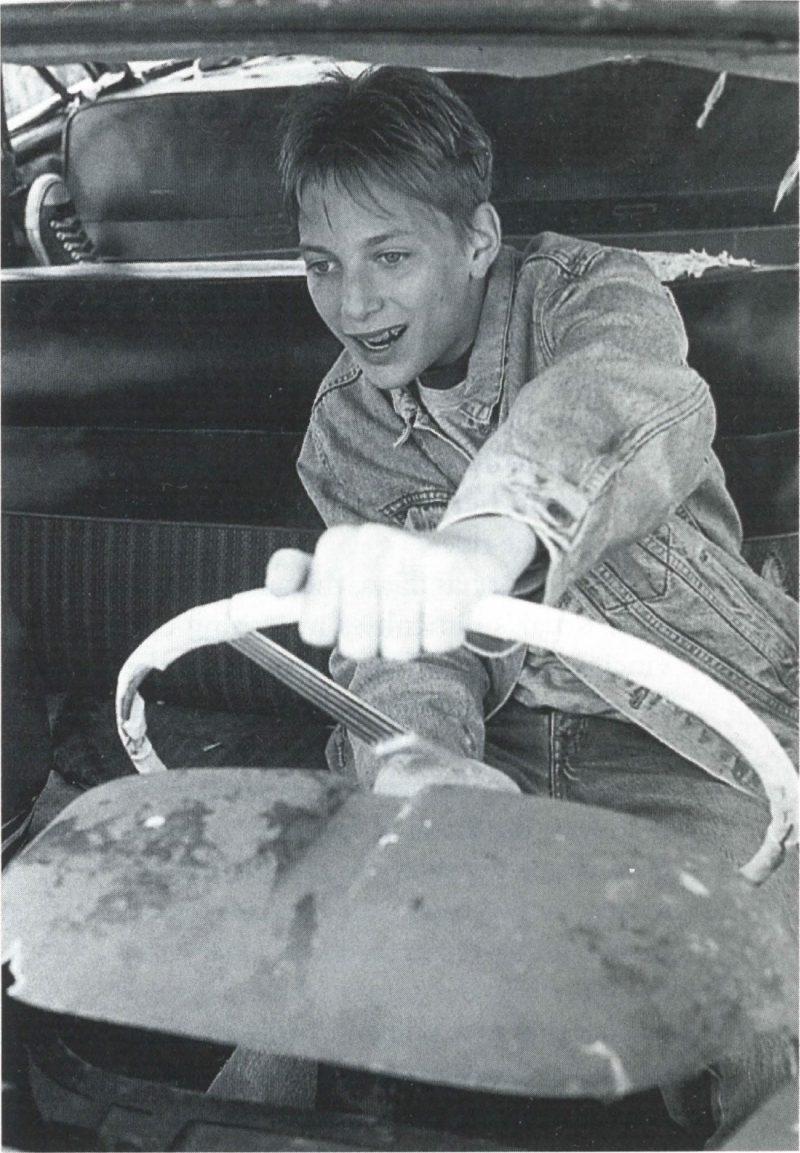

Kevin Doerksen in Hell Bent. Photographs: Robert Barrow.

As the film opens, we are introduced to the three star vagrants, already past the threshold of redemption: Marty (Daniel Sprintz), the profane loudmouth of the group, as well as the most aggressive and self-destructive; Andy (Kevin Doerksen), his darkish sidekick who’s always trying to keep up one step behind; and Leslie (Alison Northcott), a pensive, chainsmoking sociopath, who is quietly bemused by her companions’ antics. Looking for cheap thrills, Andy and Marty wreak havoc at a local convenience store, making a mess at a drink dispenser and then urinating on a customer’s car. All this gets them is a face-to-face encounter with a guidance counsellor the next day and a charge of vandalism. After he’s kicked out by his understandably enraged parents, Marty becomes even more dangerous. With his bridges fully burnt, he figures the gang should attempt a more ambitious and memorable crime. They focus their energies on breaking into the home of an elderly couple, one arthritic, the other in a wheelchair, where they inject an unbearably long and brutal session of violence and vandalism.

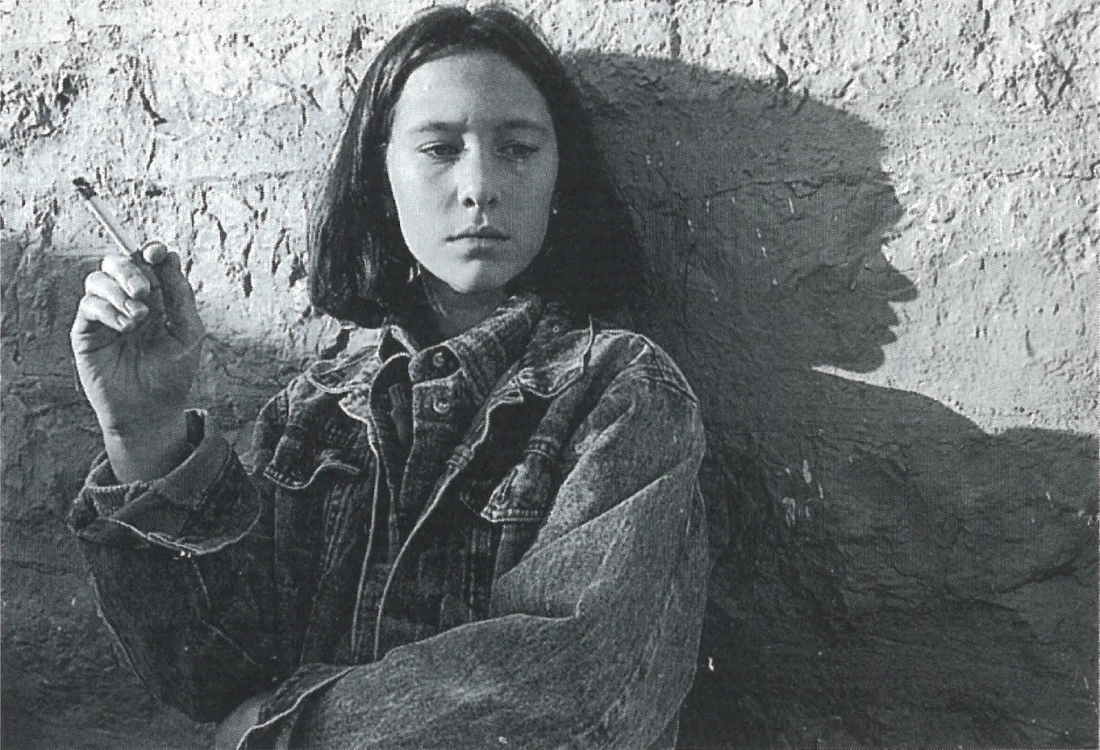

As in his previous films, including The Celestial Matter and Dory, Kozak has opted to emphasize the plot mechanics of the story itself, often at the cost of deeper insights to the issues at hand. As the writer/director Kozak doesn’t concentrate on how these kids become who they are, but rather how they go from bad to worse. While this approach may lack complexity, it still offers a straightforward and no-nonsense means of telling a story. It is also aided by a very competent cast. Sprintz delivers the best performance as an adolescent Id bereft of a Superego, brimming with pubescent rage and itching for a skull to bust. Doerksen is a bit stiff, but he still manages to balance successfully the tension between reluctant compatriot and eager punk wanabee. But of the three, it is Northcott who dominates the film with her cold stare and unfeeling persona. Paradoxically the most mature and perverse of the group, she manages to create an enigma out of a character who, unlike her partners in crime, actually sees the path to destruction before her and still decides to go along for the ride.

If Hell Bent has flaws, they usually stem from Kozak’s difficulties in writing convincing dialogue. The verbal rivalry between Andy and Marty works the best, capturing Scorcese-like banter as they try to outdo one another with mouths rather than fists. But Kozak is less adroit in situations where the three are at odds with the society around them. Adult characters are written and acted as cardboard characterizations, while the scenes where a schoolteacher tries to apprehend Leslie for smoking and where Marty gets kicked out by his abusive father, come across as forced and unconvincing. When they are not swearing or shouting, the actors are too often left to spout the obvious. And while it is commendable that the film resorts neither to psychobabble nor movie-of-the-week sentimentality, you wish that Kozak could have explained his characters’ actions beyond the usual academic reasons that they’re young, restless and ungovernable.

Alison Northcott, Hell Bent.

But Kozak still has a very firm understanding of plot structure and maps out his storyline so carefully that right from the beginning you sense these kids’ fates. If his direction gets mixed results with his cast it nonetheless maintains a strong pace: he distills an atmosphere of relentless desperation and then builds up the tension to stomach-churning levels. He’s helped in this achievement by Charles Lavack’s atmospheric imagery and Neila Benson’s tight editing. And make no mistake about it, the climax is horrible. Even the staunchest fans of cinematic gore will find it hard to stomach, which is all the more remarkable for a film where the violence never reaches the minor gratuities of a Freddy Krueger serial.

At the end, the trio is left with little to do but face their consciences, fully aware that they’re existing on borrowed time. Audiences hoping for immediate justice or onscreen catharsis will be seriously disappointed, but with Kozak’s disinterest in commenting on his characters’ inhumanity, it is an appropriate finale. How this coolly detached attitude to the crimes on-screen will be received by viewers remains to be seen. One could argue that in comparison to the stylized ultraviolence of more mainstream releases, including Pulp Fiction and Natural Born Killers, Hell Bent’s smaller bonfire of taboos are tame. Still, there is much in this film that will disturb, provoke and anger viewers. Kozak deserves credit for taking an unflinching look at the darker side of juvenile delinquency, and for doing so in a more relentless way than other filmmakers would have risked. ♦

Hell Bent, 1995, with Daniel Sprintz, Kevin Doerksen and Alison Northcott. Written and directed by John Kozak. Produced by Ken Rodeck and Phyllis Lang.

Patrick Lowe is a Winnipeg-based freelance writer and film reviewer.