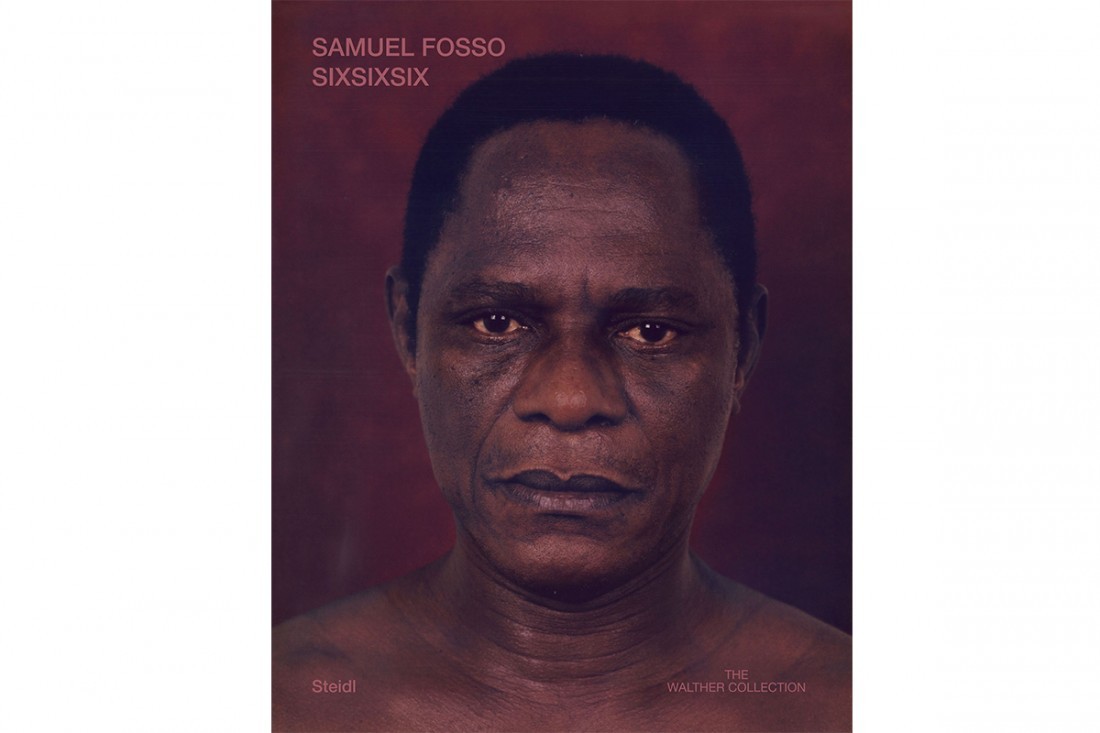

‘SIXSIXSIX’ by Samuel Fosso

The artist Samuel Fosso’s book of photographs, SIXSIXSIX, is physically dense. That is the first apparent thing before you pick it up and flip through. In fact, its very physicality might deter you from lifting it to parse through like any average photo book. And because it is somewhat atypical for its kind, it is also not easily portable. You’ll need a stable table surface to rest it on and a seat to attend to it. It looks encyclopaedic and has the weight of such a compendium. It is not a casually designed object, and because of its mass, this grouping of photographic work starts to gesture towards something sculptural as it rests in space. Like its name suggests, it has 666 pages of uninterrupted image stream with additional pages for introductions and an interview with Fosso. The content of the images in the book is a relatively simple premise: identically cropped frontal headshots of the artist seated shirtless in the same studio set-up, page after page. No further ornamentation or frills, just the artist’s bare face.

The formal constraints, seriality and permuting expressions call to mind American artist Roni Horn’s You Are the Weather, which also contains a similarly tightly cropped recurring face but reflecting the fluctuating surrounding weather through her facial expressions. All through Fosso’s monograph, we find him in numerous states of flux like the weather (but not because of it). No one capture of the artist is ever identical. The brief glimpses we catch are of his moving through several emotional registers with plain-spoken vulnerability. The images keep us on the surface of these expressions, and we are left without the specifics of why. This might be because these intimate snaps could never neatly contain the complexities of emotions he seems to be grappling with. But all together, we become witness to an elliptical portrait of the artist manifested through the hefty physicality of the book containing it. It is not necessarily definitive or exhaustive but rather suggests continuity beyond the 600-plus pages of the collection.

Fosso’s Nigerian parents were residing in West Cameroon when he was born on July 17, 1962. He was paralyzed at birth and, in a desperate search for healing, the family returned to Fosso’s grandparents in Nigeria, where he was treated and healed with local medicine. Not long after, in 1967, the calamitous Biafran War broke out, leaving them stranded in Nigeria. Fosso’s mother was among the millions who lost their lives. Fosso himself almost didn’t make it out. When the war ended in 1970, an uncle of Fosso’s back in Cameroon took him under his wing. Shortly after that, they relocated to Bangui, the capital city of the Central Republic of Africa. This is where, after stumbling on a photo studio in town, he became intrigued with taking pictures. He convinced his uncle to allow him to take up an apprenticeship with the studio owner. From there on, he studiously learned all the basics he needed in operating equipment, developing images and working with clients. After a brief dabble in street photography, mostly for practice, Fosso discovered an abandoned space that he later converted into a studio of his own at the precocious age of 13. Even though clients thought it strange that their photographer was a youngster, Fosso’s professional candour and luminous prints kept them coming back. After a day’s work, at night in the quiet studio, Fosso began imaging himself. With leftover film from shoots of the day, he’d dress up and take self-portraits with the intention of sharing them with his grandma back in Nigeria, who had no other way of seeing her grandson as he matured. This seemingly innocuous extracurricular activity, motivated by personal intent, would develop into what became his long-standing practice as an artist. SIXSIXSIX is yet another strand of the many images he’s created using his own likeness.

Unlike the spare formal qualities of the images in this new picture book, Fosso’s take on self-portraiture from his early, precocious days through his mid/ late career was always set against carefully orchestrated proscenium-like backdrops with props, makeup and costumes assembled for the occasion of the image being constructed. These crafted set designs for portrait shoots were typical of prominent photographers from neighbouring West African countries. Contemporaries in the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s, including Seydou Keïta, Malick Sidibé, Sory Sanlé and Hamidou Maiga, all documented themselves and their respective communities within studio conditions they determined themselves. But for decades to come, Fosso was the only one who stuck to his own figure as the single recurring focus in his photographs. He transitioned from taking pictures as mementos for his grandma to something increasingly theatrical, portraying versions of himself for the camera, playing invented personas and taking on impressions of real-life icons and archetypes. Over the years, the production of these images shifted and became more elaborate, coming to include production assistants, costume designers, lighting technicians and painters for his backdrops. This also meant that the characters he was inventing were just as intricate. What developed from these images were conversations on gender transgression, questions on masculinity in the African diaspora and the dramatization of historical figures, all within the newly post-colonial milieu in which he operated. For many photographers on the continent around the time of Fosso’s emergence, being behind the camera was still a new position to claim. The camera had previously been available only to the elite and was instrumental in the continent’s history of colonialism, as well as being one of the ways Europeans had represented their supposed supremacy over people they deemed “uncivilized” and in need of being “converted.” Christian missionaries used it as proof of their needed influence while Euro-anthropologists employed photography as part of their scientific study to support their theories of the racial, social and cultural inferiority of Africans. It is therefore a powerful thing for an artist-photographer like Fosso to use the camera to image himself the way he sees fit and in the way he wants to be seen. The systematized formality of the images in SIXSIXSIX mimics and upends the cold ordering of anthropological mug shots. Instead of the figure as an object of research, Fosso animates this austere space and shows us the many multidirectional ways he has been and is. Each turn of a page replaces the last, protracting the decisive moment of his image, ad infinitum. As such, Fosso offers a graceful contrapuntal to the colonial gaze concerned with subjugating his humanity.

Fosso has always used performance to reorganize felt realities by collapsing its ephemeral quality into the physical documents he outputs through his images. This was just as evident in the early works he made as a teenager—before he even considered it as an art form— and it is similarly a feature in the images in SIXSIXSIX. But in this book, iterations of which have been presented in an exhibition format, Fosso has stripped away all the flourish that came together to structure his previous visual tableaux. In fact, Fosso isn’t in character at all. What he performs here through the pages of the book comes out of deep contemplation of the past. He asserts his own presence as continuing, shifting and unpredictable, just like the realities he has had to shuffle through from birth until now. Throughout the book, we get quick snatches of Fosso pensively looking straight ahead beyond the camera or looking downcast or frustrated or lost in thought. In other instances, his brow is furrowed. But then a few pages later, his lips are curled into a slight smile. Open any random page and you might also catch him with a goofy cheer on his face. Open the book at random again and you might see him wearing a wounded expression. The portraits keep ebbing and flowing just like that. Exactly what is making him burst into laughter or come close to tears is kept off the page. We are left to merely observe these passing fragments. We will never know or fully understand, and Fosso might not necessarily want or expect us— the passive viewer—to know, at least through these flashes of images.

In 2014 Fosso’s studio in Bangui was looted during protests and unrest precipitated by the nation’s civil war decades before. During this period all his archives and studio equipment were lost and, once again, he came close to losing his life. The following year, after he tried to scrape together work for an important exhibition in Paris, the show was cancelled due to terrorist attacks nearby. Not long after, Fosso devised the SIXSIXSIX portrait series named after the misfortunes and bad luck that have surfaced throughout his life since he was a child. But more than the impetus that began it, the project intimately meditates on and catalogues lifelong experiences and encounters with elegant simplicity. In the face of constant adversity and uncertainty, this book of pictures critically reflects the persistence and endurance at the core of the human condition and the agency of narrating that condition on one’s own desired terms.❚

SIXSIXSIX by Samuel Fosso, Steidl and The Walther Collection, 2020, 680 pages, hardcover, €85.00.

Luther Konadu is a Winnipeg-based visual artist, writer and editor of the online arts publication Public Parking.