Shary Boyle

An exhibition that fits within two vitrines, “Aspects & Excess” invites close looking. In fact, these sculptures demand an intimate relationship, since each of these 31, mostly untitled figurines, made between 1998 and 2006, measures only a few centimetres. Their size bespeaks a powerful understatement; Shary Boyle’s miniatures commune in whispers that one must bend down to perceive.

Her use of polymer clay fits the contemporary DIY trend in which artists may incorporate consciously unselfconscious student-grade, suburban craft materials. For all their details, in this medium Boyle’s figures seem inchoate and vulnerable. She transforms this plastic through subtle gouache and ink touches. These little marzipans already convey the unearthly translucency of infant flesh, but her strategic blushings of faces, hands and erotogenic sites bring them to life.

To brand these works of psychological import as “surreal” may miss the point. Yes, they evoke an underlying reality and there are moments of Breton-or Bellmer-esque revelry, but Boyle reinvents pre-existing “unconscious” expressions. Like Kiki Smith, Boyle rescues feminine aspects of the psyche from eight decades of prevailing Surrealist machisme. Boyle addresses ambivalences located within the self, through which she reinterprets certain tropes of psychoanalytic iconography.

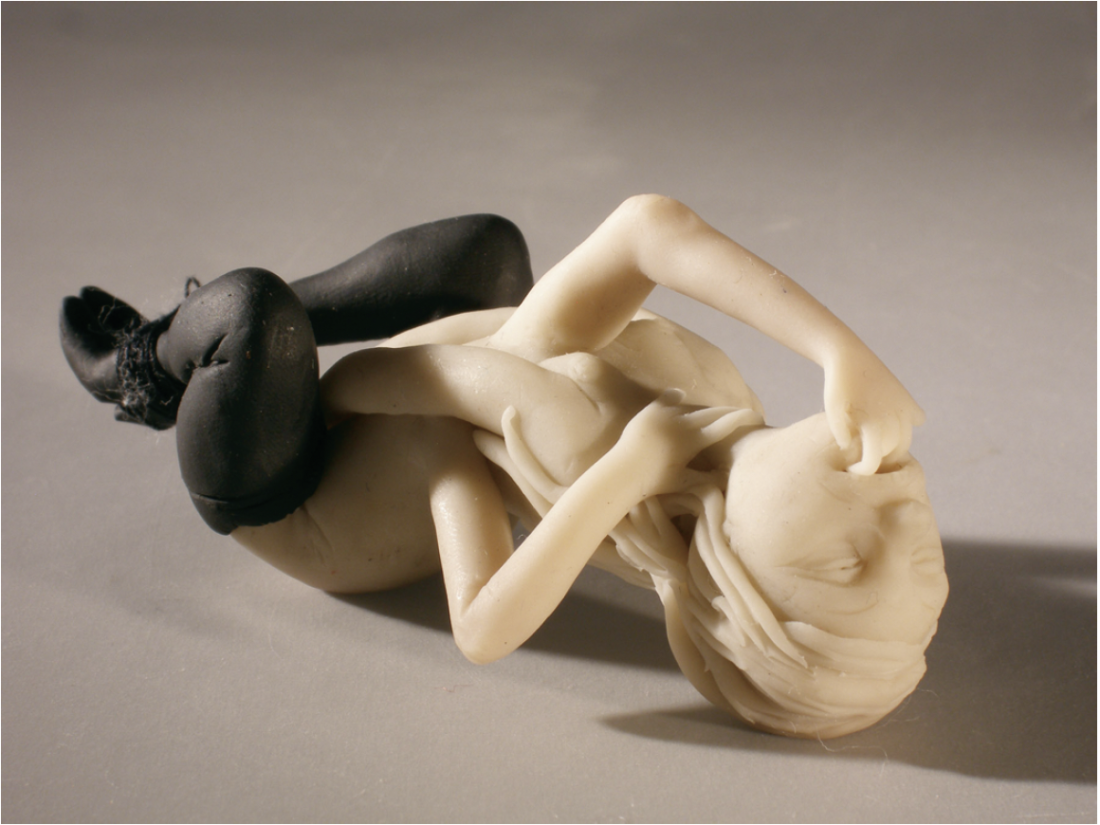

Shary Boyle, Untitled, 2001, Polymer clay, gouache, black thread, 4 cm. Photographs courtesy Canadian Clay and Glass Gallery, Waterloo.

Her equestrian statuettes, for instance, evoke the penchant for horses common among young girls. In one untitled figurine, 1999, she bridges sweet naïveté and wantonness as a naked, prepubescent female rides a kneeling black pony, bareback, arching in uninhibited rapture. In another piece, 2006, Boyle complicates this fantasy of desire as she conflates girl and pony into one, ontologically unfamiliar, body. Knock-kneed and vulnerable, this soft animal is nuzzled by a grown, similarly fleshy, but decidedly male horse.

Some works are even more overtly erotic—one hermaphroditic form, 2001, consists of legs sporting black high heels, splayed skyward, and exposing an engorged vulva penetrated by an attached member that bends away from and back into this body. Another piece from 2001 has a uniform beige tone, save black stockings and heels, and five arms that act on their own corpus. This girl seems at once to be protectively covering her pudendum, auto-eroticizing, strangling herself, muffling cries, and ecstatically biting her own fingers. A fragile black thread binds the feet and accentuates this tension between pleasure and violence.

Certain sculptures are charged through other erotics. In two different miniatures made in 2002 and 2004, Boyle shows prostrate girls, upon whose exposed flesh alight dozens of colourful butterflies. In these, the figures seem to be both consumed by the insects and surrendering to sensuality. In another work, a girl lying bare and limp is cradled, caressed and bottle-fed by an unclothed boy.

Shary Boyle, Untitled, 2006, polymer clay, gouache, 9 cm.

In order to direct identifications of their dramatis personae, some pieces are titled. The baseness of a male drinking fluids that stream from between feminine legs is mitigated, even mythically ennobled, when one realizes they are the Water & Grass, corresponding to their blue and green skins. Another pairing of little gods, Dirt & Leaves, shows two figures that reach out to each other: a muddied androgyne sprung from some soil stretches towards a standing boy who wears moss trousers and sprouts verdant vines from his back.

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Boyle’s sculpture is her ability to communicate through minute gestures. Tiny, pedomorphic faces can express contentment, sexual satisfaction, terror or ambiguous combinations of these feelings; clenched toes or thrown-back hair may accentuate such emotions. Already suggestive as lumps of flesh, each diminutive nude is further fetishistically charged by Boyle’s insistence that they wear shoes, ankle socks, or some other accoutrement. There are wonderful instances in which Boyle does not paint the figures’ high-heeled shoes that read, then, as organic appendages. For example, in a statuette fusing a skyward-pointing penis with kneeling female legs, this footed detail trumps the sexual resonance of the larger juxtaposition. Here, and in other works, the fetishist’s displaced desires become resolutely corporeal.

“Aspects & Excess” conveys a psychology that seems both widely shared and deeply personal, since Boyle’s mostly female and Caucasian- peachy forms seem to be surrogates for the artist herself. These miniatures are caught somewhere between childhood and adulthood; they manifest the magical fantasies of children trying to make sense of the world, the adult mind working through childhood’s traumas, and this inner life’s interconnected condensations. ■

“Aspects & Excess” was exhibited at the Canadian Clay & Glass Gallery in Waterloo, Ontario, from January 14 to March 25, 2007.

William Ganis is a professor of art history at Wells College, Aurora, New York.