“Shards”

An all-women’s show, “Shards” gathered artists at different points in their careers: KC Adams, Jaime Black, Lita Fontaine and Niki Little, and was curated by Jenny Western. At the opening and in the catalogue, Dr Julie Nagam provided an oral and written response from a curatorial perspective. “Shards” presents contemporary works in dialogue with historical ceramic pots suggested to have been made by women thousands of years ago, and which were borrowed from the collections of the University of Winnipeg’s Department of Anthropology and the Manitoba Museum Collection. The pots were constructed from shards of clay in the manner of their former shape and were displayed on plinths covered with Plexiglas tops. These clay shards served as reference, guidance, and acted as silent ancestors in the gallery space, presiding over the new works made by contemporary Indigenous artists from this region. The shards are storied remnants holding the imprints of women’s hands, evoking their identities through the makers’ marks. They also act as artifactual witnesses and evidence to support women’s enduring continuance in caretaking for their families and communities. Displaying historical works in tandem with contemporary artwork is a recurring theme in many contemporary exhibitions and serves as a way of recognizing a lineage of knowledge and practice throughout the generations.

Lita Fontaine, Red Shawls (Tipi Cover 1), 2017, mixed media and found objects, 64 x 36 inches. All images courtesy Gallery 1C03, University of Winnipeg.

Historical objects displayed in this context set a code, a framework for material use, for aesthetics and meaning. The placement of the contemporary work transcends these traditions in the same manner, in accordance with the 21st century’s layered critique and technique. In the process of production, and for research, the artists met with Manitoba Museum curator of archaeology Dr Kevin Brownlee and University of Winnipeg curator of anthropology Dr Val McKinley to learn about the shards in the collections. Adams and Little also travelled to Minnesota and participated in a short-term residency with experimental archaeologist Grant Goltz, who shared his theories on the production of the original vessel makers. After these research phases, each of the artists approached her work in very different ways. In conversation with the shards, the artists went beyond pottery methods and treatments into conceptual, discipline-crossing responses that conversed not only with the ancients but also among each other.

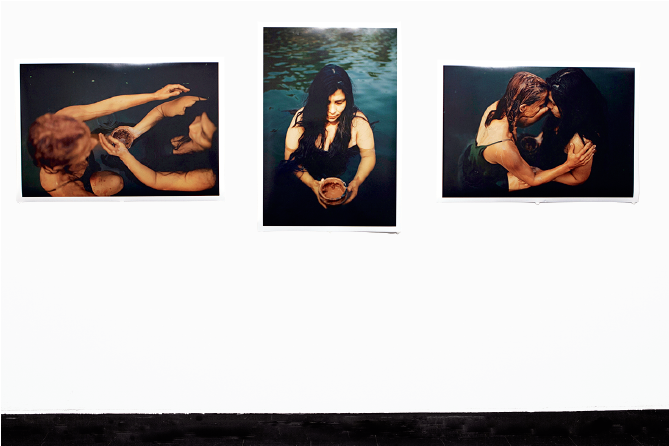

On the opening night, Jaime Black performed with KC Adams. It began with Black encased inside a Plexiglas box, her breath casting a fog on the glass as she slowly felt her way around the confined space. With the help of Adams, the box was lifted while they both sang a song from Adams’s installation. I wondered, if the 2,000-year-old ceramics of our forbearers could converse, what would they say? The reference to the subjectivity of cultural material and its confinement to colonial interpretation in museological collections and display was demonstrated and felt. Black enacted a rejection of the enduring gaze and speculation upon Indigenous bodies in the museum context in a manner similar to what James Luna had done in his iconic The Artifact Piece. However, Black pushed this further by ceremonially demonstrating the strength of women’s kinship, their integral roles in community and the process towards self-determination in these spaces. She ended her performance by claiming space and drawing a finger-painted thunderbird woman in red-ochre coloured clay slip on a monument-sized rock outside the university. Black’s untitled photographic triptych captures the essence of these demonstrations in a tender embrace with KC Adams.

Jaime Black, untitled, 2017, archival inkjet prints, 36 x 24 inches each.

Niki Little’s work, Embed, explored the relationship of mother and daughter with a self-portrait photo of Little and her daughter, who pose together in a vulnerable yet courageous naked embrace. The photo is nestled inside the bottom of sculptural bags that emulate the shape of a pregnant womb. The sculptures are constructed from fabric bags created by KC Adams, which are replications of fabric bags that helped shape the pot in the traditional production process. Together, the photograph and fabric bags capture the dedicated practice of motherhood and the laborious construction of creating tools, like the fabric bags, to make pots that provide for family and community, the work functioning as an homage to taking care.

KC Adams took up the traditional processes and techniques learned from her time with Goltz and injected new ideas, combining them with her experience of working with clay for many years, and producing here a multi-faceted installation. It consists of “nipekos-kopanin e-kiweyan (I awaken as I come home),” ceramic vessels with decorative textual treatments and surface embellishments, and the video nii wawaa ichi gamin (we create a circle), which lay in what resembled a hearth or campfire, as though the pots were actively being fired. As you approached the work and looked closely into one of the clay vessels, a video screen was visible through the wild rice, presenting a performance at a water gathering, where the responsibilities of both men and women are balanced. What was heard was a song that described their roles in firing the clay pots. This work was presented in the middle of the gallery and carried the practices of function and convention, but transcended convention by adding technology and sound. These are traditional resurgences into the present, and the work is alive—leaving the viewer with a sense of smelling the fire and being at the ceremony.

Jaime Black and KC Adams performance.

KC Adams, nipêkopanin ê-kîwêyân (i awaken as i come home), detail, 2017, mixed media installation, 144 x 36 x 12 inches.

Lita Fontaine’s work stood apart from the group. She chose an interestingly different path and materiality in her work, Red Shawls, which represents a “protective covering of the shawl and the tipi.” Fontaine’s two works side by side are semicircle tipi covers in painted canvas, inspired by a Women’s Sun Dance she had attended. Raising the tipi and sewing the hide or canvas together was traditionally the women’s role, so the matrilineal work is not lost here. Fontaine also looked to the shards more metaphorically, as a “brokenness and fragility” felt by community members reeling from missing and murdered loved ones, women whose lives were cut short by endemic conditions. Fontaine refers to the shards in her work through the inclusion of broken pieces of clear quartz, serving as a reminder of the fragile past, present and future. The red-shawled women are huddled together around the semicircle and look away from the viewer, which could be read as refusal to engage, or as protection of something that is out of sight; of course, you could also say they are looking into the future for hope.

By laying fertile ground for creative exploration in the phases of research, “Shards” presented personally involved work that allowed each of the artists to take her own path. These explorations produced work with distinguished characteristics. I was, however, curious about both Black’s and Little’s work encircling Adams’s work, without a curatorial reason presented for their collaboration or inclusions. Perhaps knowing this would have further expanded the connection to, and process of, the exhibition. No matter, the artists activated the dormant shards and spoke eloquently of our past and present through their powerful remnants. ❚

“Shards: Contemporary Artists in Conversation with the Ceramics of Our Forbearers” was exhibited at Gallery 1C03, Winnipeg, from September 14 to December 2, 2017.

Jaimie Isaac is the curator of Indigenous and Contemporary Art at the Winnipeg Art Gallery. She is an interdisciplinary artist and co-founder of The Ephemeral Collective. Isaac is a member of Sagkeeng First Nation, of Anishnaabe and British heritage.