“Shapeshifters, Time Travellers and Storytellers”

It would hardly be fair if I were a restaurant critic and dismissed a menu simply because I couldn’t stand the dishware, but that’s what I’m going to do here. It certainly wasn’t auspicious when one architecture critic recently voted Daniel Libeskind’s crystalline addition to the Royal Ontario Museum last year’s Building Most Likely to Come Down in the Next 20 Years, but then again, another writer thought the museum’s Institute of Contemporary Culture (found within the big crystal) was one of the city’s best new exhibition spaces. That writer’s choice, however, was based mostly on the custom-built case Hiroshi Sugimoto designed to display his work in the gallery’s inaugural exhibition. It left with Sugimoto. The current show, “Shapeshifters, Time Travellers, and Storytellers,” of a number of contemporary Aboriginal artists interspersed with some artefacts from the ROM’s collections, has to make do with the star-architect’s cockeyed attempt at making the old new.

Kent Monkman, Duel After the Masquerade, 2007, acrylic on canvas. Images courtesy the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto.

I’ll forego any discussion of his exterior and concentrate on the still-white, but no longer cubic, space that contains the work I’m supposed to be writing about. Libeskind’s design flaws are best represented by the plinth that houses the gallery’s fire hose. For whatever regulatory or engineering reasons, this essential element of the building—the type of thing I’m sure most, if not all, forward-thinking architects wish they could do away with as it only acts as an obstacle to their vision— cannot be discreetly recessed into an available vertical wall because there aren’t any, so it must sit in its own minor monolith, slightly out onto the gallery floor. The clumsiness of this permanent protuberance is echoed by the temporary contrivances that have been built to support or otherwise contain the artwork and accompanying texts and credits that make up the exhibition. To wax metaphorically, my interest in seeing the trees was consistently hampered by how unattractive the forest was.

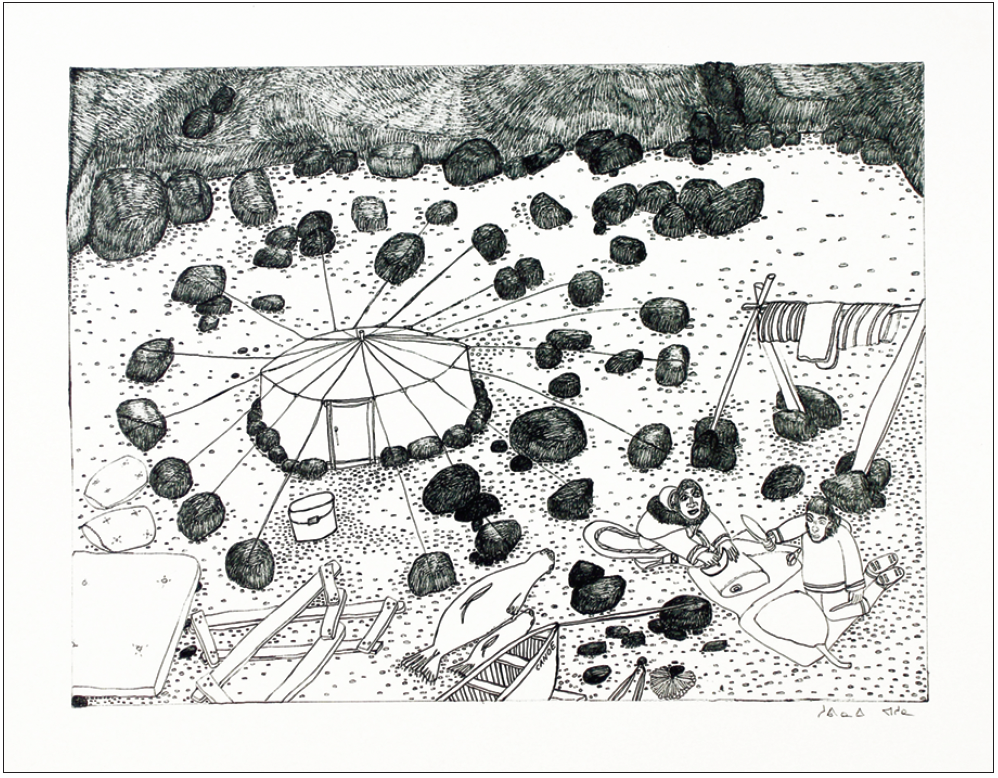

Shuvinai Ashoona, Composition (Camp Scene), Cape Dorset, 2007, ink, 20 x 26”. Photograph courtesy Feheley Fine Arts, Toronto.

On entering the gallery, the first thing you see is the curator’s recourse to a traditional museum space, an L-shaped section of rust-coloured wall with wood grain mouldings at the top and bottom. This simulated setting for New York-based artist Alan Michelson’s landscapes of the setting sun, near motionless videos housed in classically appointed painting frames, is meant to evoke the kind of gallery that once was all you could find in an institution like the ROM. Unfortunately, any dialogue with the past (and past methods of representing the past’s past) intended by placing such contemporary work in an historical museum is defeated as the ROM has done the opposite: it has made the museum too contemporary.

Alan Michelson, Of Light After Darkness, 2007, video installation with gilded frames. Installation view at the Royal Ontario Museum.

A similar loss is felt with the inclusion of Toronto artist Kent Monkman’s specially commissioned retort to a Paul Kane painting (taken from the museum’s collection) of preening Aboriginal men. Setting myth against myth, Monkman queers the script and contributes an equally sexualized canvas that begs to be inserted in the First Nations galleries. There it would wreak havoc on unsuspecting viewers; here it just seems like a bitchy tribute. Due to the aforementioned lack of vertical walls, these canvases are hung on the back of a display case that holds Monkman’s updated artefacts for the fashion-forward Aboriginal person. His Louis Vuitton Quiver and Dreamcatcher Bra also deserve spots in the historical galleries. If you’re going to bring them this far, you might as well go all the way.

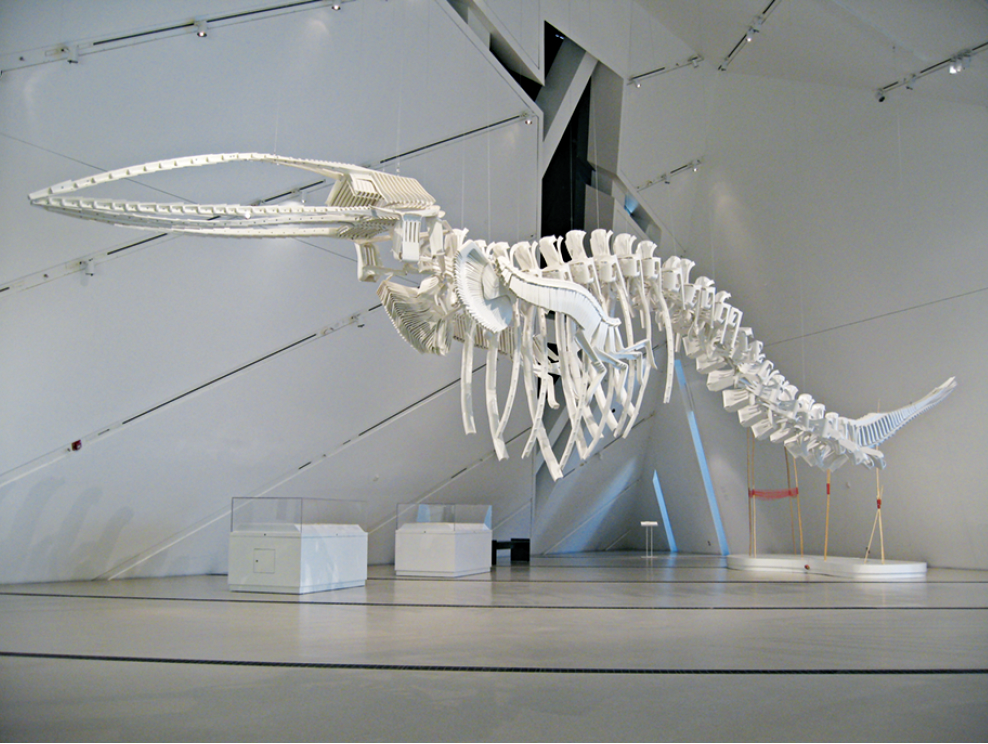

The only artist who vaguely holds his own in Libeskind’s cavern is Brian Jungen. His lawn chair whale skeleton hangs down from the cleft ceiling like the kind of alien beast that has drawn the curious to museums since such institutions first went public. Due to the ROM’s staggered opening schedule, I’ve yet to see the new dinosaur galleries, but according to all reports they’re a swinging success. Judging from Jungen’s piece and assuming the other new spaces are much like this one, I’m not surprised. They’re CAVES! Of course they suit the dinosaurs!

Brian Jungen, Cetology, 2002, plastic and metal, installation view at the Royal Ontario Museum. Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery.

On the title wall, co-curators Kerry Swanson and Candice Hopkins write they were looking to “expand the discourse regarding the role of the museum as a container for the interpretation of culture.” It’s unfortunate that they were saddled with such an ungainly container, one that distances itself from the history on which they want to expand. Despite these distractions, Swanson and Hopkins make the most of their location when they include such time-shifting and telling artefacts as Robert Flaherty’s drawings from Nunavut. Made 10 years before he directed Nanook of the North, the 1923 movie whose images became indelible icons of the Inuit, they are placed alongside contemporary Cape Dorset artist Suvinai Ashoona’s cluttered drawings. Her landscapes are full of frantic detail, not just expanses of snow. They depict a version of the North in stark contrast to Flaherty’s sparse images. This simple and judicious conjunction, merging “past and present, truth and fiction, story and reality” as the curators intended, brings far more to the table than any multi-million-dollar redecoration. ■

“Shapeshifters, Time Travellers, and Storytellers” was exhibited at the Royal Ontario Museum’s Institute for Contemporary Culture from October 6, 2007, to February 28, 2008.

Terence Dick is a writer who lives in Toronto.