Seeing VALIE EXPORT Photographically

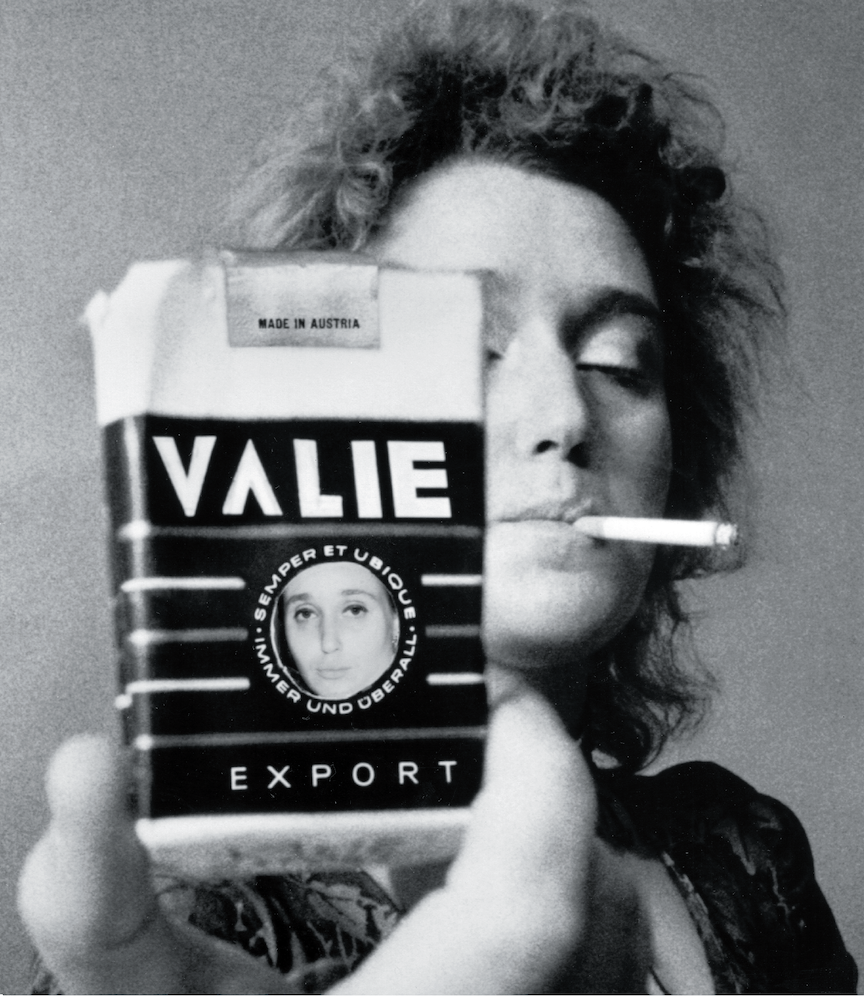

VALIE EXPORT, VALIE EXPORT – SMART EXPORT, 1970, self-portrait. Collection of Albertina Museum, Vienna, The ESSL Collection. Photo: Gertraud Wolfschwenger. © VALIE EXPORT, Bildrecht Wien, 2024 / Bildrecht, Vienna 2024. Courtesy C/O Berlin Foundation, Berlin, and VALIE EXPORT FILMPRODUKTIONSGESELLSCHAFT mbH.

One would expect a venue larger than C/O Berlin to host VALIE EXPORT’s first comprehensive solo presentation in many years. Indeed, a good portion of the internationally renowned Austrian artist’s oeuvre had to remain unseen, which made “VALIE EXPORT: Retrospective” a somewhat disingenuous title. On the other hand, the non-profit exhibition space’s focus on photography cast an artist known primarily for her provocative performances in a different light. While the show did emphasize the now canonical performances from the ’60s and ’70s, which most of us know only through films and photographs, it is not just the pragmatics of documentation that led to an exhibition in a photography museum. Film and photography have formed the basis of the artist’s practice from the very start. For EXPORT, who has also been writing critical texts on lens-based media and the role of women in society since 1972, photography is not just a medium but a “conceptual apparatus.” It offers a guiding methodology for her drawing, sculpture, public art and, of course, her pioneering performances, many of which were staged for the camera. EXPORT has always implicitly understood what Susan Sontag later called “photographic seeing,” and consequently strove to develop self-critical as well as emancipatory possibilities for the medium. These resulted in works that do not always look like film or photographs but nevertheless employ the camera as an actual and metaphorical lens for another way of looking at the world and also at oneself.

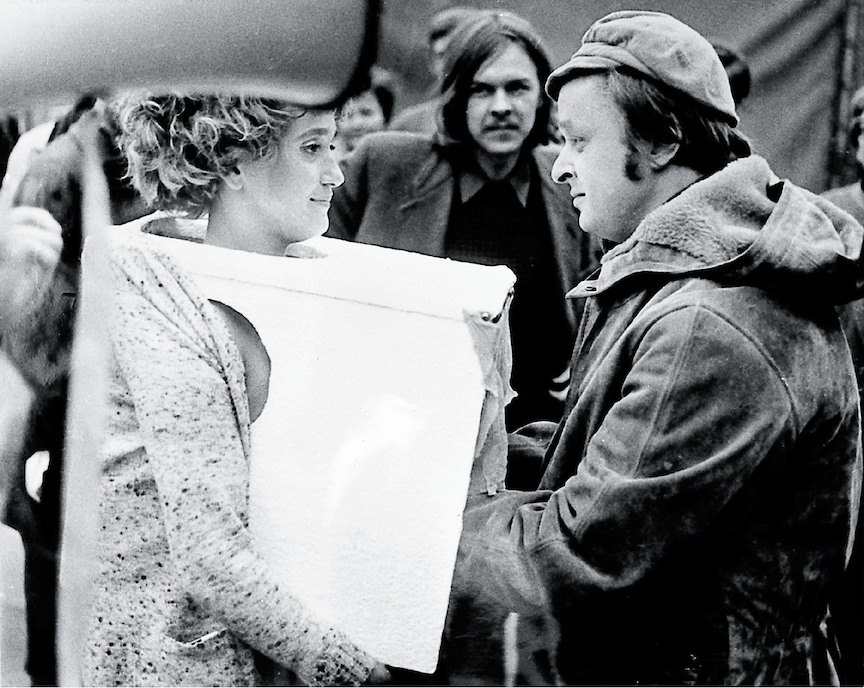

TAPP und TASTKINO (GROPE and TOUCH CINEMA), 1968. Collection of Albertina Museum, Vienna, The ESSL Collection. Photo: Werner Schulz. © VALIE EXPORT, Bildrecht Wien, 2024 / Bildrecht, Vienna 2024. Courtesy C/O Berlin Foundation, Berlin, and VALIE EXPORT FILMPRODUKTIONSGESELLSCHAFT mbH.

The packed opening at C/O Berlin was, as many art shows are, filled with people observing each other and themselves as often as, or in some cases more than, they were looking at art. Some were taking selfies in front of large self-portraits of EXPORT, thus inviting a comparison between two types of self-portrayal across time, as well as demonstrating just how relevant the artist’s output remains today. Sontag’s formulation of “photographic seeing” rightly positioned photography as more than a medium, and this mode of looking has arguably only grown in importance over time. Today it might be better reformulated as “photographic being.” We are constantly being filmed, tracked and recorded—by ourselves, by friends and family, by machines or surveillance cameras. Our images feed algorithms that feed models that produce pictures indistinguishable from photographs or offer us a world that reflects our biases. We in turn understand ourselves increasingly as images, especially when we scrutinize our faces in our smart phone while taking a selfie (or many selfies, so as to capture just the right one), when our expressions and eye movements are tracked for commercial purposes, when we curate our social media accounts, our online profiles and our online “presence” in general. Our being is not limited to our body but extends to our representations and the tangible traces of intangible gestures that we leave behind. We must always be, in the most extended sense of the term, “camera-ready.”

BODY SIGN B, 1970, self-staging. Collection of Albertina Museum, Vienna, The ESSL Collection. Photo: Gertraud Wolfschwenger. © VALIE EXPORT, Bildrecht Wien, 2024 / Bildrecht, Vienna 2024. Courtesy C/O Berlin Foundation, Berlin, and VALIE EXPORT FILMPRODUKTIONSGESELLSCHAFT mbH.

In his 2019 book Selfies, German theorist and art historian Wolfgang Ullrich argues that the selfie turns the self into an image. That is to say, the self is not represented by an image, and neither is it expressed through an image, but it literally becomes an image. This means that the picture gains weight in the definition of being. For Ullrich, this development is not a damning diagnosis of narcissism or digital addiction, but simply a technological innovation analogous to the printing press. Selfies, he writes, are the facial expressions and body language that we otherwise lose in a society where text is produced just as quickly and informally as spoken language. They are as fleeting as a smirk, a blink, or any other subtle gesture that lends nuance and intimacy to the words we speak. While Ullrich’s observations are convincing, they do not address the larger network existing around the phenomena of the selfie, namely the one made and moulded by commercial interests. In its self-conscious staging and online dissemination, the selfie can be compared to what artists do when they make self-portraits and circulate them in a visual discourse of images. EXPORT knew this in her appropriation of the EXPORT ‘A’ cigarette brand and in the way she stylized her name as an artist into a logo, requiring that it always be written in capitals. She manipulated consumer iconographies with the goal of denaturalizing the norms of female representation. In contrast, EXPORT’s contemporary and equally important performance art pioneer Marina Abramovi´c wholly embraced the logic of the image. Her face has become a multinational brand, whose visual identity she is now at great pains to preserve, as is the case with other recognizable celebrities. It is thus only a logical development that she uses it to sell limited-edition skin-care products. Rather than remaining herself, Abramovi´c has become her own image. EXPORT’s tongue-in-cheek brand is, as others have already pointed out, too varied and unstable to be truly marketable. Perhaps this is why she has succeeded in earning an income from her art so late in her career—just in the last 15 years, she says, in an interview with the Süddeutsche Zeitung. Moreover, the photographic portrayal of the artist’s body has gradually given way to a variable and complex exploration of representation. Ultimately, EXPORT questions the possibility of self-representation, often differentiating between the various German terms for self-portraiture—Selbstbildnis (self-portrait), Selbstaufnahme (self-recording), Selbstinszenierung (self-staging), to name just a few. She does not, however, abandon the image as such. Instead, she uses it as a critical tool in relation to itself and the human being it is supposed to portray.

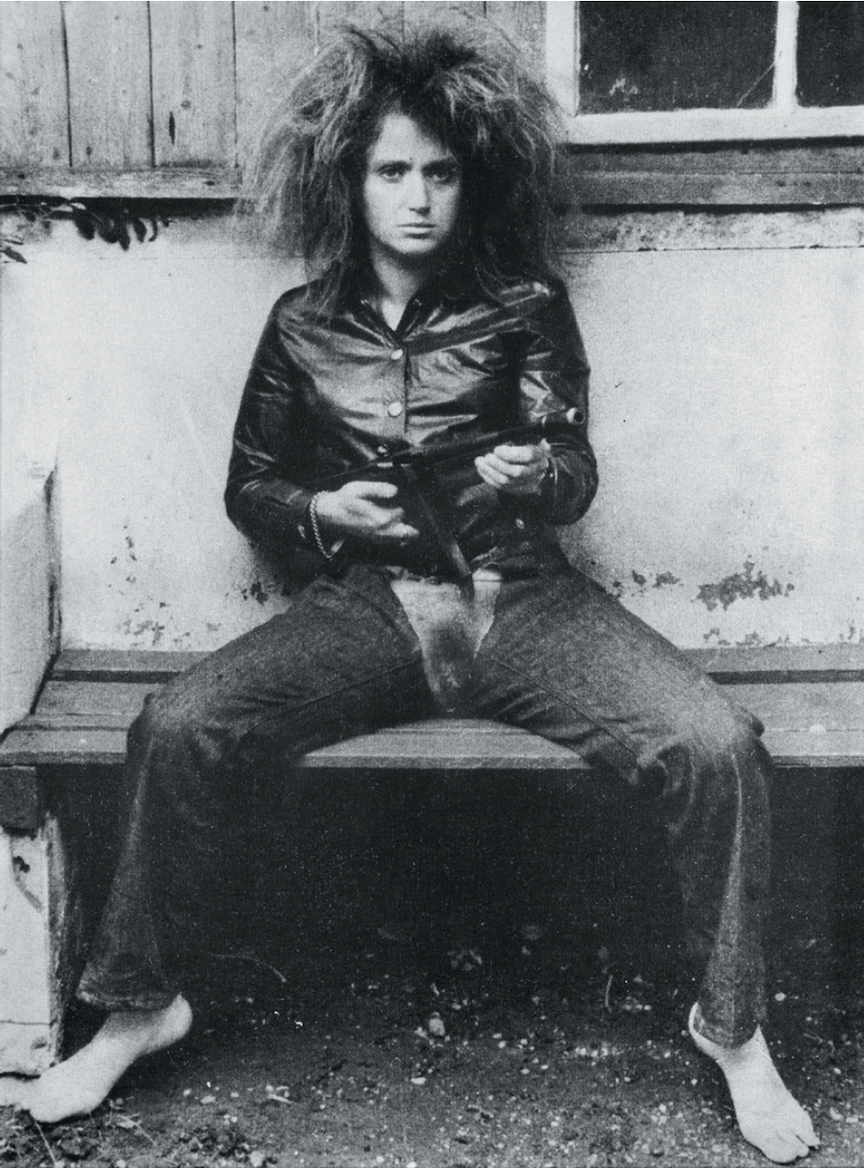

Action Pants: Genital Panic, 1969, selfstaging. Photo: Peter Hassmann. © VALIE EXPORT, Bildrecht Wien, 2024 / Bildrecht, Vienna 2024. Courtesy C/O Berlin Foundation, Berlin, and VALIE EXPORT FILMPRODUKTIONSGESELLSCHAFT mbH. 68084int.

The press image for “Retrospective” is Genital Panic, 1969, one of EXPORT’s early “expanded cinema” works, which, along with TOUCH CINEMA, 1968, is preserved as an iconic photograph recognizable beyond the art world itself. Both were confrontational performances in which EXPORT inserted her real body between the viewer and the viewed object so as to break from the screen as a site onto which desire is projected. Desire is implicit in the gaze of the camera, which, EXPORT says, not only observes like the eye of the beholder but also observes the act of perception. This means that the audience is pulled into the perceptual habits of the photographer, in addition to being subjected to the perceptual limitations of the camera. While there is room for interpretation between the eye of the camera and the eyes of the audience, this interpretative space is markedly different from the looking that happens in real life. The frame, the cut and other filmic strategies offer the audience a reality that demands nothing of them, thus creating a space for fantasy. In TOUCH CINEMA, EXPORT subverted this frame by building a new one: a tiny theatre in the form of a small box over her breasts through which the “viewer” does not see but touches the object of desire. In a video interview, EXPORT remembers that the facial expressions of the “voyeurs” ended up being more important than the act of touching. Because the performance happened on the street, their gazes were not only filmed but exposed to the public, and to EXPORT as well, who would at times make eye contact with the (most often) men reaching for her body. Genital Panic was also a cinematic intervention, from which just a photograph remains and whose status as an image might paradoxically reproduce the very influences she was working against. EXPORT walked between the rows of a film theatre wearing pants from which the crotch was cut out. Her groin was confrontationally presented at the eye level of the viewer, thus blocking the screen but also “facing” the gaze of the audience. Confronted with the real thing, the viewer is no longer capable of sinking into fantasy.

In On Photography, Susan Sontag wrote that “despite the illusion of giving understanding, what seeing through photographs really invites is an acquisitive relation to the world.” This is likely equally true for both photography and cinema, which have in the course of time—through YouTube, GIFs, reels, among other things—inched closer together. They both share, to quote Sontag again, a “consumer’s relation to events.” For EXPORT, this acquisitive relation is primarily a masculine orientation, because, as she wrote in “Women’s Art: A Manifesto” in 1972, men control “social and communication media.” If “reality is a social construction and men its engineers,” she continues, “women must participate in the construction of reality via the building stones of media-communication.” “Retrospective” shows that this call to action means more than generating new representations of women; it means undermining the consumerist predilections of photography. Parallel to her performances and expanded cinema works, which critiqued the cultural projection of the female body, EXPORT was already exploring how photography could offer new possibilities of seeing and being.

Figuration Varation C, 1972, gelatin silver print with ink, 41.7 × 65.6 centimetres. Photo: © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, New York. © ARS, New York. Acquired through the courtesy of Charles Heilbronn.

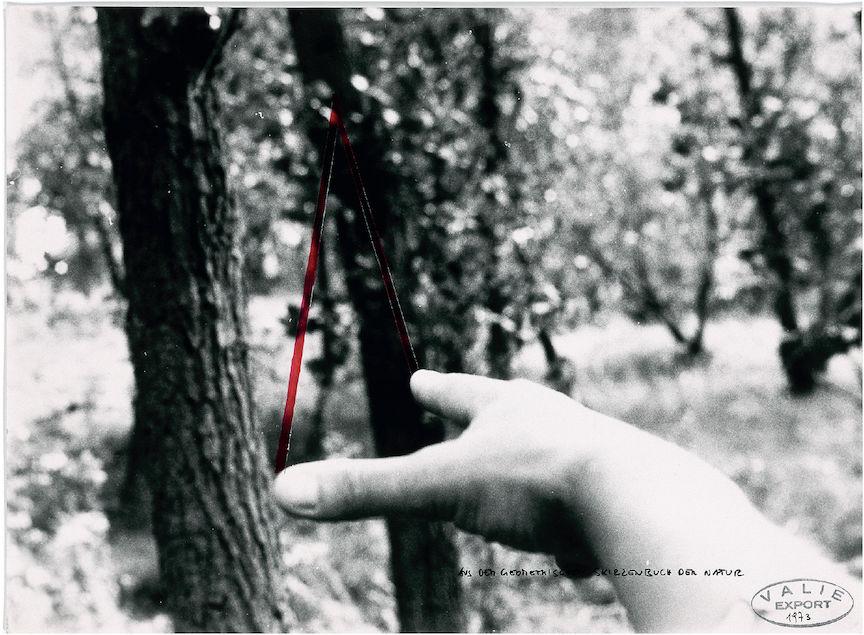

Her work shifts from a focus on the seen body to the body as seeing subject in what is ultimately a continuation of an epistemological question: How can one know the self? The combined drawn and photographed images from “From the Humanoid Sketchbook of Nature,” a series that started in the early ’70s, directly juxtapose different methods of picturing the self. Instead of EXPORT presenting her body to the world, whether in front of an audience or as a brand, we see cropped images of body parts: feet, hands, a real hand holding a photographic hand, a neck extended with graphite into a mountain or volcano. One gets the sense that the artist is observing herself, or observing how she observes, rather than offering an image to the public. Furthermore, the combination of mediums and layering of images bridge different types of representation; it seems to be an attempt to reach beyond the social construction of reality. In Adjunct Dislocations, 1973, EXPORT wears two cameras—one on her chest and the other on her back—to record the world from the perspective of her torso. These two viewpoints are then cut together and shown side by side. Here the camera is separated from the observing eye. The unintuitive and limited perspectives highlight the importance of framing as an aesthetic device and also point to the shortcomings of seeing as a mode of understanding—a connection that is even linguistically conflated in English.

The artist’s mixing of mediums and increasingly abstract approach were not steps toward the abandonment of film and photography but an attempt to reach beyond the photographic being. The logic of expanded cinema continued to guide this inquiry, though the approach was metaphorical rather than representational. The cut, for example, is a concept poached from the language of cinematic montage and reinterpreted in performances incorporating self-injury or used as a compositional method, as it often was in the series “Body Configurations,” 1972–82, in which EXPORT’s body cut into or through the landscape. The mechanics of cinema thus provided a metaphorical basis for an exploration of self, narrative and form. A very early example is Cutting, 1967–68, in which a building’s facade was projected onto a piece of paper and its windows were “opened” by slicing into the paper. Other cuts within the work included cutting a logo out of a T-shirt and shaving body hair. Later, a fully different type of work took a sculptural approach to cinema. Fragments of the Images of a Caress, 1994, is a room-sized sculptural installation that sounds like a film. Eighteen light bulbs are suspended from metal bars that are in turn attached to a grid suspended from the ceiling. Each bulb is slowly dipped into a cylinder of water, a milky substance or oil. The number 18 corresponds to the minimum amount of frames needed to attain fluid motion in film; the black, white and transparent liquids correspond to the colour values of black and white film; and the installation itself sounds like a running projector.

Encirclement, from the series “Body Configurations,” 1976, gelatin silver print with red ink, 35.5 × 59.6 centimetres. Collection of The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Carl Jacobs Fund. Photo: © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, New York. © ARS, New York.

“Body Configurations” remains one of EXPORT’s most startlingly beautiful series and it charts a changing orientation in relation to the body. The large-format black and white photographs are simultaneously formal explorations and interjections into patriarchal structures as embodied by edifice. EXPORT’s body, or, from 1976 onwards, that of her model, is no longer a projection of Woman but an architectural feature itself—a move that anticipates her assertion in a 1987 essay that a woman’s body is always familiar and foreign, human and object. The occasional addition of drawn elements complements the line of the body and makes the photographs read like drawings, which many do anyway due to the framing and the flatness of the black and white image. A number of “Body Configurations” also take place in nature, especially in dune landscapes, to which EXPORT repeatedly returned. Later, in From the Geometric Sketchbook of Nature: Geometric Figurations in the Dune Landscape, 2012, which was not a part of “Retrospective,” the human body disappears and the drawn lines extend as sculptural elements out of the photos into the room itself.

The disappearance of the body is not a disappearance of the self. It is a questioning of the effectiveness of representation in creating and accessing reality. In a 1987 essay “The Real and Its Double: The Body,” EXPORT states that the body is a cultural construct and concludes that the woman must release herself from the body and the image of Woman in order to become a sovereign self. This idea manifests in imageless self-portraits that are part of her later lesser-known works, many of which were not shown at C/O Berlin. Traces: ID-GRAVIS, 2000–01, for example, is a transparent, folding room divider upon which EXPORT’s genetic code is printed. Later works that were included in the show included I turn over the pictures of my voice in my head, 2008, and Die Macht der Sprache (Power of Speech), 2002, where the glottis was filmed while she was speaking with the use of a laryngoscope. These videos are difficult to look at, even if one is not particularly squeamish. The opening and closing vocal chords look medical yet vaguely sexual, both human and foreign. This alienating interiority is a failed search for the self as well as—what is also a thread in EXPORT’s work—a focus on the voice rather than image as a means of self-actualization. To this end one cannot ignore her extensive writing, which remains just as essential to her practice as her visual output.

Aus dem geometrischen Skizzenbuch der Natur: BAUMDREIECK (From the Geometric Sketchbook of Nature: TREE TRIANGLE), 1973. © VALIE EXPORT, Bildrecht Wien, 2024 / Bildrecht, Vienna 2024. Courtesy C/O Berlin Foundation, Berlin, and VALIE EXPORT FILMPRODUKTIONSGESELLSCHAFT mbH.

EXPORT’s assertion that the woman is both Self and Other echoes John Berger’s claim that in contrast to men who “look at women,” “women watch themselves being looked at.” It is a dubious “progress” of sorts, that this once-gendered problem takes on a pan-gendered relevance in our time. As a result of ubiquitous photography and data collection, not least due to the self-conscious taking and distribution of the selfie, most people watch themselves being looked at, even if they are just watching themselves being looked at by themselves. This growing feedback loop opens even larger problems in regards to the politics of seeing, representation and self-identification, as well. Against the background of this phenomenon, the vanishing image of the body in EXPORT’s work functions not only as critique but as an attempt to configure a new relationship to representation. Photography is abandoned as a way of seeing and being; it comes to serve as a metaphor. It is used to question the primacy of sight, which is problematically conflated with understanding, and representation, which in turn is conflated with political determination. EXPORT’s approach differentiates and keeps nuances intact. It guards against a world where the image of the person substitutes for their agency. ❚

Aus der Mappe der Hundigkeit (From the Portfolio of Dogness), 1968, in cooperation with Peter Weibel. Photo: Joseph Tandl. © VALIE EXPORT, Bildrecht Wien, 2024 / Bildrecht, Vienna 2024. Courtesy C/O Berlin Foundation, Berlin, and VALIE EXPORT FILMPRODUKTIONSGESELLSCHAFT mbH.

“VALIE EXPORT: Retrospective” was organized by C/O Berlin Foundation and ALBERTINA Museum and was first on exhibition at the ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna, from June 23, 2023, to October 1, 2023. It then toured to C/O Berlin, Berlin, from January 27, 2024, to May 21, 2024. A portion of this exhibition, “VALIE EXPORT: The Photographs,” was exhibited at Fotomuseum Winterthur, Winterthur, from February 25, 2023, to May 29, 2023.

Dagmara Genda is an artist and writer living in Berlin.